What is stone skipping? The art of throwing flat rocks across the water has become a semi-professional sport involving technique and science.

The goal of stone skipping, also known as stone skimming, is to see how many times a stone bounces off the surface of a pond before sinking.

Believe it or not, skipping stones is more than just a pastime and has become a highly competitive outdoor activity with thousands of participants and fans.

It looks simple and easy, but there’s a lot of training involved.

The perfect stone skipping technique takes years to perfect and master and involves physical prowess and scientific knowledge.

The first written record of stone skipping as a sport dates back to 1583.

Some sources believe that it all began when an English king skipped sovereigns – British gold coins – across River Thames, in London.

The future of stone skipping is bright.

The challenges ahead are enough to keep its large community of followers and recreational enthusiasts excited and active.

Will anyone skip a stone 100 times? How far can it travel? And if curling made it, why can’t stone skimming become an Olympic sport?

The Science Behind Stone Skimming

Skipping stones is an old scientific dilemma. How does a stone skip across the water? Why does it bounce so many times?

Lazzaro Spallanzani (1729-1799), an Italian Catholic priest, was the first to provide an early explanation for the physics of stone skimming.

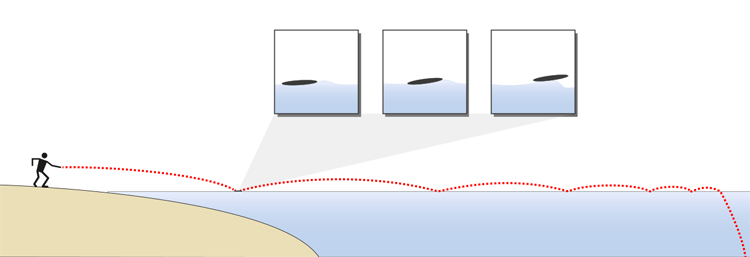

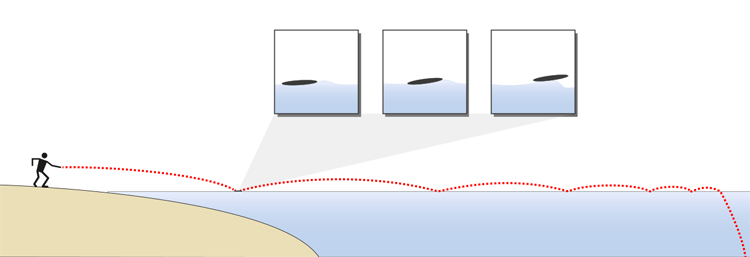

When thrown like a flying disc, the rock generated lift by pushing water down as it travels across the water at an angle.

The stone’s rotation acts to stabilize it against the torque of lift being applied to the back.

In 2002, Lydéric Bocquet, a French physicist at the University of Lyon, published a scientific paper titled “The physics of stone skipping,” in which he dissects the phenomenon.

He discovered that the mass of the stone, its angle to the horizon and the surface of the water, its spin rate, and horizontal velocity determine whether the rock sinks or skims.

Bocquet concluded that small angles – around 20 degrees – combined with high spin rates result in an optimal toss. So, the initial “flick” is critical to a successful throw.

In 2011, I. J. Hewitt, N. J. Balmforth, and J. N. McElwaine also pointed out that, in theory, a skipping stone will bounce indefinitely across the water if the horizontal speed can be maintained.

Skipping stones spend 100 times longer in the air than they do on the water.

And because air is 784 times less dense than water, its impact on the rock’s flight is relatively minimal.

We could say stone skimming is a miracle of fluid dynamics. But there’s more it than math and science.

The Guinness World Record

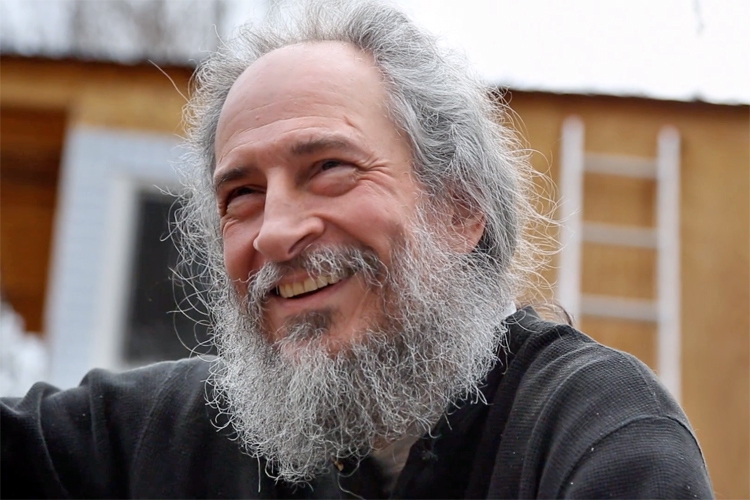

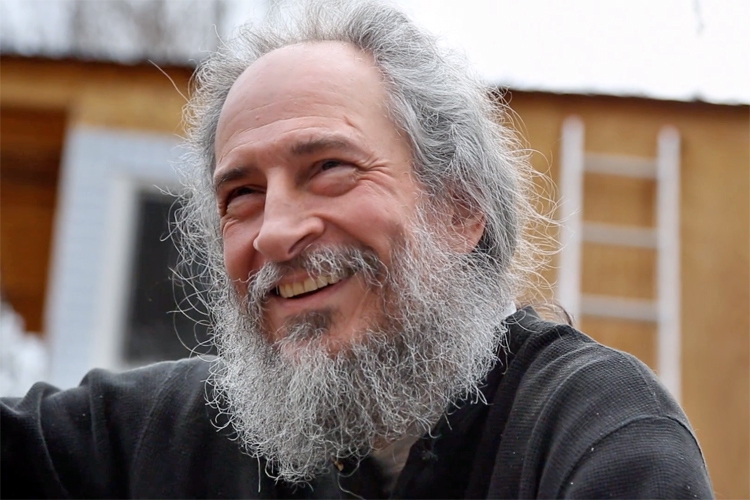

Kurt “Mountain-Man” Steiner currently holds the Guinness World Record for the most consecutive skips of a stone on water.

On September 6, 2013, Steiner managed to get his skipping stone touch the water 88 times at Red Bridge, in the Allegheny National Forest (ANF), Pennsylvania.

But his achievement was not a stroke of luck. The truth is that he had been training years for the moment.

Kurt collects several thousands of “quality stones” from Lake Erie and sorts each according to its type to have the best possible throws.

There are different shapes for different skips and conditions, just like a surfer or skimboarder picks a board from his quiver for a specific type of wave.

It’s paramount to choose your weapon wisely – “Mountain Man” has triangle, square, and circle-shaped stones for all situations.

His favorite rocks weigh between three and eight ounces (85-225 grams) and need to be between 1/4 and 5/16 inch thick (6.4-8 millimeters).

These stones do not have to perfectly round, but they need to be extremely smooth and have flat bottoms.

Kurt is a zen-like character who puts his mind and soul into the sport.

He developed his own tossing style, which somehow defies science’s paradigms regarding optimal skimming stone formulas.

Steiner prefers to throw his stones fast at 30 degrees to an imaginary horizontal line, swiveling his shoulder back and bringing his arm like a whip.

When the stone is thrown, it looks like it is going almost directly into the water, except by the time it hits the water, it’s not actually going directly down and then comes out at about five degrees.

Funnily enough, Kurt never counts his skips.

How to Skip Stones

How do you skip a stone across an ocean, lake, river, or body of water? Here are a few tips that will help you become a better and more talented stone skipper.

The first thing you have to do is determine which side is going to be down. Flatter and slightly rounded are good; if it’s cupped or jagged, put that up.

There are several valid stone skimming techniques, involving grips and stances.

It all depends on the water conditions, the stones you have, and distance versus skip count goals.

For example, if you’re aiming for multiple skips, you should attack the surface of the water with a steep rock release.

In calm, waveless, flat waters, you should focus on tossing the stone close to shore.

If the first initial bounces are good, chances are the quality of the throw will also be high.

“The more force that is applied, the more critical the landing conditions become, and the more precise the release must be,” explains Kurt Steiner.

The brief time between release and the first skip – less than a second – is enough to change the landing orientation of the stone.

Under high rotational and forward velocity, non-flat stones experience significant aerodynamic effects.

You might want to select rocks that spin aerodynamically against the gyroscopic twist, similar to the vertical propeller on a helicopter.

“Especially with lighter, spinnier stones, I try to get the first skip to land within 10 feet of my release, and the second skip to land within ten feet of the first,” adds the current Guinness Record Holder.

“When I drive a rock – a horizontal throw, rather than a downward whip – it can feel like I’m laying it down gently on the water because I release it so low to the surface.”

One final word of advice: stone skimming can cause injuries. So, make sure to warm-up your muscles before trying your luck.

Throwing Stones for World Titles

The World Stone Skimming Championships have been running since 1989.

The North American Stone Skipping Association (NASSA) ran the World Stone Skimming Championships between 1989 and 1992 in Wimberley, Texas.

Since 1997, the event is held in Easdale Island, Scotland. It’s the spiritual home of the sport.

The competition features five divisions: adults (male and female competitors aged 16 years or more), juniors (boys and girls aged 10-15 years inclusive), children (kids aged nine years and under), old tossers (male and female competitors aged 60 or more) and team (maximum of four athletes of either gender and any age mix).

The overall winner is declared world champion.

The Competitive Rules of the Sport

In a competitive environment, the rules are simple:

1. All stones must be no more than three inches in diameter at its widest point;

2. Each contestant will have three skims per session;

3. The stone must bounce on the surface of the water at least two times to be considered a valid skim. The length of the skim is judged until the stone sinks into the water. The longest skim in each division will be deemed the winner;

4. Competitors are not allowed a “run-up” when throwing. As a result, both feet must be on the platform when throwing;

5. Valid skims will be signaled with a green disk, and invalid skims will get a red disk.

6. A skim will be deemed invalid if:

a) the stone does not bounce at least two times;

b) the stone does not sink within the competition area;

7. In case of a tie, the overall champion will be decided by the cumulative distance of a three-skim “toss-off.” A “back wall” hit counts as 63 meters. In the event of a tie in all other categories, rankings will be decided on a cumulative total of all three stones skimmed.

Competitors do not need to bring their own “equipment” – skipping stones made of Easdale slate are available for all athletes.

Stone Skipper for a Living

“Skips Stones for Fudge” is a 2016 documentary by Ryan Seitz that chronicles the life of two legends of the sport – Russ “Rock Bottom” Byars and Kurt “Mountain Man” Steiner.

The duo battled each other competitively for over a decade and pushed the boundaries of stone skimming to the limits.

The film explores the physical and emotional challenges stone skippers face to stay at the top of their game while young guns make their way into the limelight.

Byars passed away in October 2017, aged 54.

BBC Scotland also produced “Sink or Skim,” an in-depth documentary on the sport, which reveals how stone skipping has been playing a considerable role in the development of Easdale Island.

Stone Skipping | List of World Champions

2019: Peter Szep (HUN)

2018: Peter Szep (HUN)

2017: Keisuke Hashimoto (JAP)

2016: Dougie Isaacs (JAP)

2015: Dougie Isaacs (JAP)

2014: Dougie Isaacs (JAP)

2013: Dougie Isaacs (JAP)

2012: Ron Long (WAL)

2011: Dougie Isaacs (JAP)

2010: Dougie Isaacs (JAP)

2009: David Gee (ENG)

2008: Eric Robertson (JAP)

2007: Dougie Isaacs (JAP)

2006: Tony Kynn (AUS)

2005: Dougie Isaacs (JAP)

2004: Andrew McKinna (JAP)

2003: Ian Brown (JAP)

2002: Alastair Judkins (NZL)

2001: Iain MacGregor (AUS)

2000: Scott Finnie (JAP)

1999: Ian Shellcock (ENG)

1998: Ian Shellcock (ENG)

1997: Ian Sherriff (ENG)

1993: David Rhys-Jones, Jonathan Ford Joint, Matthew Burnham

Recent Comments