Click here if you are unable to view the photos on a mobile device.

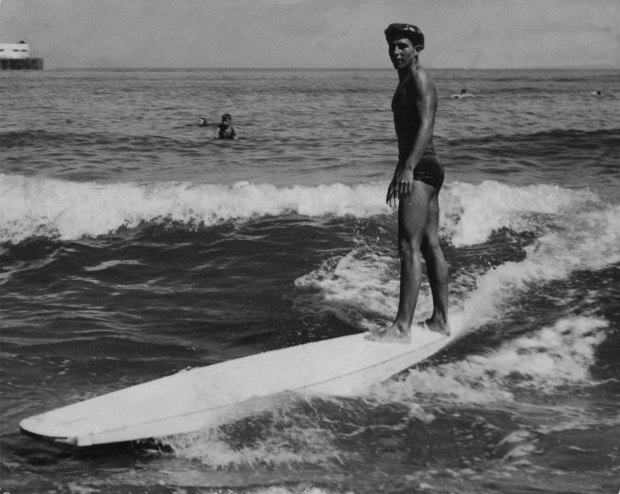

Surfing has held a mystical allure in Santa Cruz for well more than a century. But there was a time when the practice didn’t exist there — or anywhere in North America.

Until, suddenly, it did.

As the legend goes, it was a warm July day in 1885, when three young Hawaiian princes plunged into the waters at the mouth of the San Lorenzo River and, to the amazement of those watching from the beach, began riding the waves atop long, heavy planks made of local redwood.

“I’m sure everyone was astounded,” says Kim Stoner, a lifelong surfer and Santa Cruz historian. “They were probably going, ‘Wow, those guys are walking on water!’”

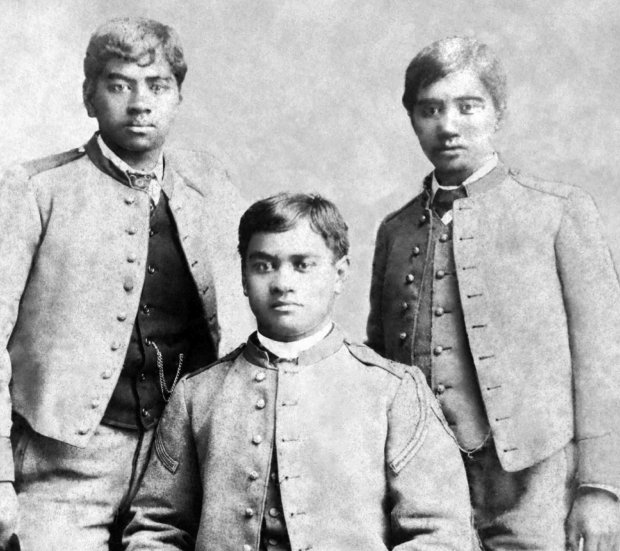

David Kawananakoa, Edward Keli’iahonui and Jonah Kuhio Kalaniana’ole, nephews of King Kalakaua, were on a break from a military school in San Mateo and spending an idyllic summer with a prominent Santa Cruz family. Their longboard escapades were chronicled in a local newspaper article — the first documented evidence of surfing on the U.S. mainland.

These adventurous teen royals, of course, were simply hanging loose and enjoying a ritual ingrained in their island heritage. They couldn’t have known that this and future visits would help shape the cultural identity of Santa Cruz — or that they’d someday be commemorated on a plaque along West Cliff Drive.

Or that two of the hulking boards they rode would find their way back from Hawaii 130 years later and become part of a stirring 2015 exhibit that set attendance records at the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History.

“I tell you I get chicken skin just talking about it,” says Bob Pearson, a well-known Santa Cruz surfboard shaper who was part of the team behind the exhibit and who believes those princely boards are “insanely precious.”

“They’re like the Holy Grail,” he insists.

For Pearson and other longtime Santa Cruz surfers, few things in life can beat shredding the breaks at Steamer Lane or Pleasure Point. Richard Schmidt, who has run a surf school here since 1978, says growing up among the waves blessed him with “a magical sense of wonderment that never fades.” Jane McKenzie, the president of the Santa Cruz Longboard Union, calls being out on the ocean “kind of like my church.”

But they get almost as stoked when discussing the colorful surfing history and culture that permeates their quirky, laid-back seaside community.

Hang with them for a while, and they’ll regale you with stories about local legends of days gone by who fueled the sport’s evolution. They’ll fondly recall how the late Jack O’Neill revolutionized cold-water surfing with the invention of the wetsuit, and with great pride, they’ll school anyone who will listen that Santa Cruz has been formally recognized as a World Surfing Reserve, in part, because of its “pervasive and deep-rooted surf culture.”

Says McKenzie, “You have a lot of people here who not only love surfing, but who are absolutely passionate about the history.”

And one of the great things about Santa Cruz is that history is easily accessible. You can snap selfies in front of the 18-foot bronze surfer sculpture, erected in 1992 in memory of Santa Cruz Surfing Club founding member Bill Lidderdale. Or you might choose to chill out at the Jack O’Neill Restaurant & Lounge, when it reopens at the Dream Inn, which offers grand views of Monterey Bay and is adorned with mementos paying tribute to the late visionary.

And the city, of course, is teeming with super-cool surf shops that carry the latest boards and wares.

But the essential place to start is the quaint Santa Cruz Surfing Museum, when it reopens at the Mark Abbott Memorial Lighthouse on West Cliff Drive. This little gem, which first opened in 1986, packs a lot of memorabilia into a small amount of space, including vintage photographs, videos and artifacts tracing more than 100 years of surfing life in the region.

“There’s so much in there, and we’re kind of tapped out for space,” says Stoner, one of the museum’s founders. “But we like it the way it is.”

Among the treasures inside are photos of members of the first local surf club, which had humble beginnings in 1936 in the basement of surfer David “Buster” Steward’s parents’ home. In addition, homage is paid to the pop-cultural impact of surfing (including the classic film “Endless Summer”). And there’s an exhibit that documents the ever-changing makeup of surfboards — from those big primitive slabs of wood to the sleek and flashy fiberglass rides of today.

Howard “Boots” McGhee, a longtime local surfer and environmentalist, has treated countless school kids to tours of the museum over the years and never tires of watching them fawn over the boards or become “dead silent” when they see one that was chomped by a shark.

McGhee loves the “can-do ideology” exuded by the museum and marvels at how it opens up a whole new culture to many visitors.

“I’ve seen a lot of people come here from all over the world who know nothing about surfing,” he says, “And they end up going home with $35 T-shirts.”

But perhaps the best thing about the museum is outside. It’s perched on a bluff above the body of water known as Steamer Lane. Here, you can join awestruck landlubbers along the railing to watch the thrill-seekers below dance upon the waves in one of the most famous surf spots in the world. (While there, check out the plaque dedicated to those Hawaiian princes).

If you’re inspired, you’ll actually want to get into the water. As McKenzie says, “When you sit in the ocean, it’s a much different experience than standing on a cliff and looking at it. The tactile dimension is totally different. Even watching the sunset is different.”

That said, a great place to earn your stripes is Cowell Beach, sometimes described as the “bunny slope” of surfing. Located in front of the Dream Inn, it features a sandy bottom and gentle breaking waves. It’s where Schmidt and other instructors teach beginners the fundamentals — and etiquette — of surfing.

But be forewarned that plenty of people these days have the same idea. McGhee compares trying to break into the local lineups “to pulling into a crowded freeway.” And Schmidt admits that he has had to turn some customers away during the pandemic.

“People want to get out into the ocean. They need a release,” he says.

But Schmidt insists that, for those who do manage to venture out there and find their mojo atop a surfboard, there’s nothing else like it.

“I love seeing the thrill students get,” he says, “when they can harness the energy and the surge of the ocean.”

And follow in the footsteps of those three Hawaiian princes.

Recent Comments