LARGE AND IN CHARGE: A white shark cruises off Fish Hoek beach, in Cape Town’s False Bay. This photo was taken by the Shark Spotters research team while trying to tag great white sharks along the inshore areas of False Bay in 2006 to learn more about their inshore patterns of behaviour. The team has published several papers on this behaviour now. Picture: © Alison Kock.

A brush with his own mortality stoked big wave rider and adventurer Greg Bertish into launching Shark Spotters – an internationally acclaimed bathing safety project that’s doing wonders for shark conservation.

“Shark!” a scream goes up. Chaos and confusion erupt. Panicked surfers claw their way to the safety of the shore, waving and shouting to warn others. Hysteria spreads through the packed, murky waters at Cape Town’s Muizenberg Beach.

Greg Bertish was among them. A big wave surfer and veteran waterman, he had been making the most of the sunny weather and small, glassy water to teach a few friends how to surf when the warning reached them. They scrabbled to join the mass exodus to the safety of the sand. It took a further 15 minutes before everyone was out.

That was in August of 2004 and at the time sharks were on every Cape Town surfer’s mind. Four months earlier, also at Muizenberg, a wave dyed red with blood washed over surfer John Paul “JP” Andrew, 16. Most of the teen’s right leg had been bitten off by a great white, but despite massive blood loss, JP survived.

Horror

Less than a year earlier, in September 2003, a shark killed David Bornman while bodyboarding, at Noordhoek. Fellow surfers watched in horror as what was believed to have been a great white dragged the 19-year-old underwater before breaking the surface and tossing him in the air. Bornman was helped to shore, but bled to death in minutes.

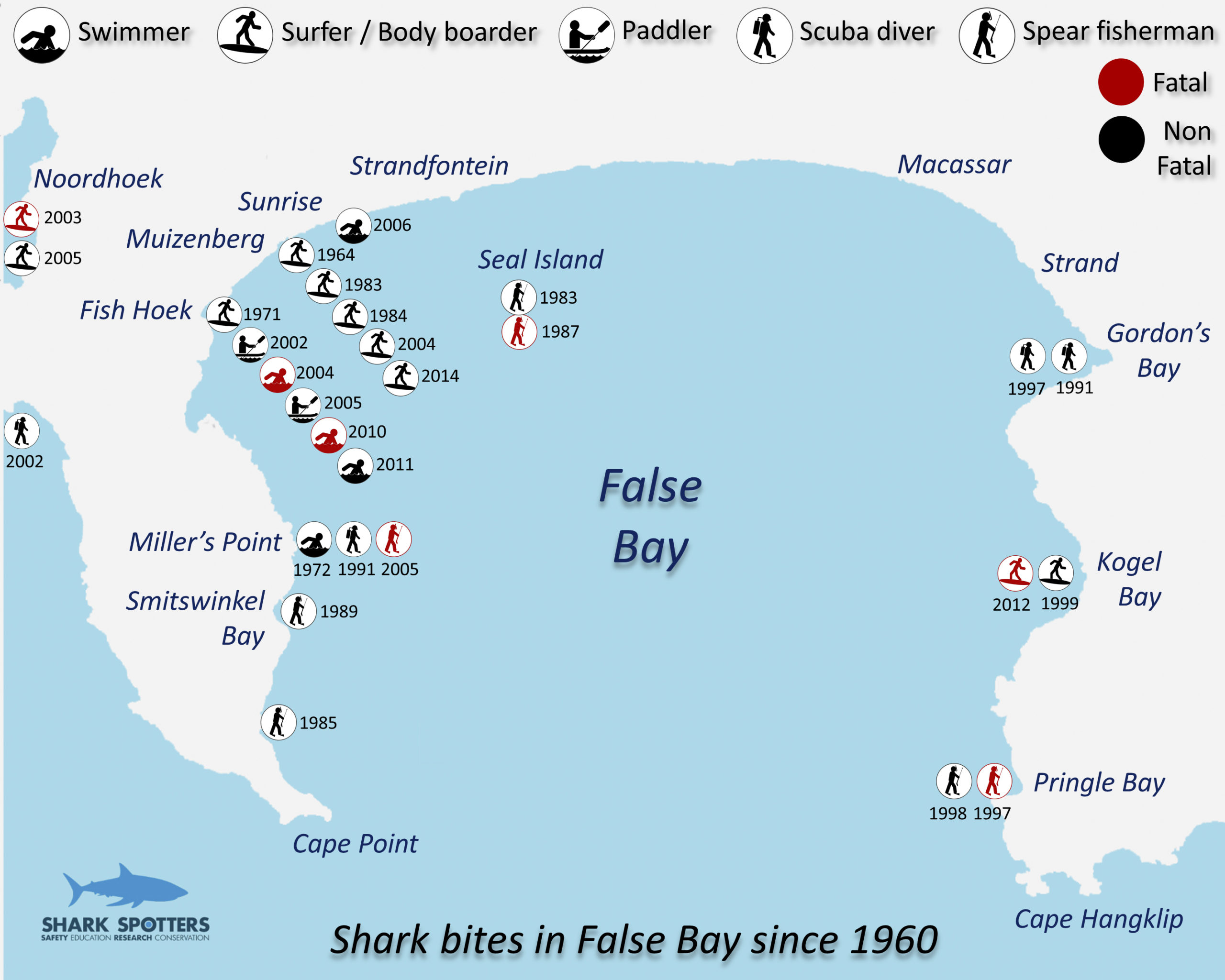

Noordhoek is a half hour’s drive from Muizenberg, on the western side of the Cape Peninsula, which separates False Bay from the Atlantic. Twenty-eight shark bite incidents have been reported in the greater Cape Town area since 1960. All but three were in False Bay, which is home to one of the world’s largest gatherings of great white sharks.

For months, Bertish’s thoughts kept drifting back to that day in August. Something had to be done. But surfers, fishermen and marine biologists struggled to agree on what. Nor could City of Cape Town officials, residents and business owners see eye to eye.

There were proposals to shoot sharks or put in shark nets and drum lines. But these measures drew a storm of protest from ocean lovers and biologists, concerned that nets would kill not only sharks but other large marine animals, like dolphins, turtles and whales. Drum lines were hardly better. These use large baited hooks and are notorious for killing dolphins and rays as well as sharks. Most of the proposals turned on culling sharks. Fewer sharks would mean fewer incidents involving sharks, so the reasoning went.

Discussions dragged on and nothing happened. Gatvol, Bertish decided to take matters into his own hands, steeled by surviving a trauma of his own. Two years earlier he had nearly lost his life to endocarditis, a rare tropical bacterial disease that attacks the heart’s valves. After lying low for a year, recovering, Bertish emerged rejuvenated – “high on life and getting back into the ocean”.

He felt he’d “been given a second chance… I thought I couldn’t fail, or I didn’t care if I failed,” he told Roving Reporters.

Speedo Man

It helped too that he had spent many years risking life and limb, surfing some of the biggest waves on the planet and that he was not beyond bending a few rules to get things done. He came up with a plan, drawing on his love of the ocean and a lifetime’s experience of the sea, including a spell of lifesaving. (When he was 20, during his compulsory military service, Bertish trained as a lifesaver at swish Clifton. It was a good way to dodge guard duty and instead spend time in a Speedo on the beach.)

He also called on his brother, Connor Bertish’s experience working with trek fishermen. Trek fishing is a traditional form of fishing in the Cape. One end of a net stays on the beach while the other is rowed out in a small boat to surround a school of fish, before being pulled, or trekked, back to shore.

Trek fishermen send scouts up the mountain at Muizenberg to spot schools. Bertish knew they sometimes saw big sharks cruising into False Bay. Here was the germ of an idea that would become “Shark Spotters” – a non-lethal solution, a way of achieving some distance between surfers and sharks.

Initially the idea was met with general scepticism.

“Everyone laughed at me, thought it was a stupid idea, a crazy idea. I think I didn’t care because I had just overcome such a huge setback in my life and survived. I think therefore starting Shark Spotters and being laughed at and failing would just be like water off a duck’s back compared to what I’d been through,” he said.

Toilet block capers

In the dead of night, Bertish and brother-in-law, Rory Heard, slinked down to the toilet block at Muizenberg beach and bolted an old military siren and a flagpole to it. With friends, Dave and Fiona Chudleigh, from the Surf Shack surf shop, he recruited Monwabisi Sikweyiya, an unemployed lifeguard, and Rasta Davids, a car guard, as the first two members of the Shark Spotters crew.

Sikweyiya was stationed on the mountain with binoculars, looking out for sharks, with Davids on the beach. When Sikweyiya spotted a shark he would radio Davids, who would sound the siren and raise a shark flag.

Humble Beginnings

Both the siren and flagpole are still in use at Muizenberg today, but the project has evolved and expanded considerably. Shark Spotters now monitor four beaches year round – Muizenberg, Fish Hoek, Caves and St James. And they keep watch at an additional four beaches – Clovelly, Glencairn, The Hoek and Monwabisi – in summer, from September to April, as well as on weekends, public holidays and during school holidays.

Spotting is vital in summer because that’s when great whites spend more time near the shore (or at least they used to, but more on that in a moment), catching reef fish as their offshore food supply of baby seals dwindles. It’s also when people pack the beaches to enjoy the sun.

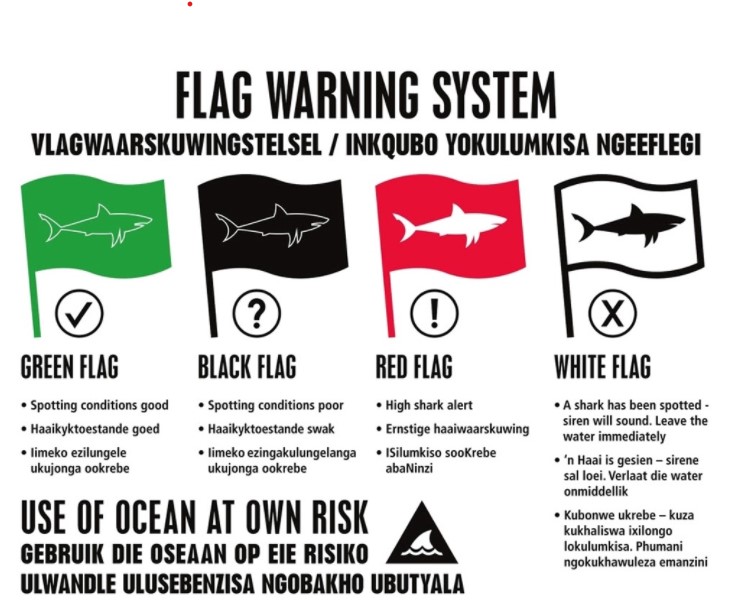

Shark Spotters use a colour-coded flag system to warn the public when sharks have been seen or when shark spotting conditions are poor, which depends largely on the clarity of the water.

It took some moxie to get the project going – and money too. Initially, Bertish scraped funds together to pay the Spotters from donation tins in local shops and contributions from the surf community, surf shops, surf magazines, and surf events. But after it had been running for a year and a half and had proved its worth, the City of Cape Town municipality backed the project to the hilt. The municipality was now one of its two primary funders, the other being the Save Our Seas Foundation.

Success but with limits

Since Shark Spotters started in 2004 – believed to be a first of its kind at the time – the team has recorded more than 2,020 shark sightings. And such has been its success that in 2015, an international review ranked Shark Spotters as the top shark bite prevention measure in a review of bather protection technologies. The review, commissioned by the Australian government, found it to be the only shark mitigation measure to meet all the criteria necessary for it to be implemented immediately at beaches in Australia. A scientific report also confirmed that Shark Spotters’ sirens and flag system had indeed proved effective in reducing the “spatial overlap” between white sharks and water users.

Even the best systems have their limits, though. Conditions must be good for shark spotting to be reliable. And when it isn’t, bathers and surfers need to heed the black flag warning them that Spotters were struggling to spot.

And so it was on 1 August 2014, with cloud cover and haze making it hard to see into the sea, when Matthew Smithers went surfing far down Muizenberg beach in an area outside the spotting area. The 20-year-old was attacked by a suspected great white and suffered several deep cuts to his legs. A black flag had been flapping in the breeze in the shark spotting area indicating spotting conditions were poor.

There has been only one (presumed) fatal attack at a Shark Spotters beach while Spotters were on duty. It happened in 2010 at Fish Hoek, also in poor spotting conditions. Lloyd Skinner, an engineer from Zimbabwe, had been standing in the sea, chest deep. He was 100 metres from the shore, adjusting his goggles when a shark struck him. It was “longer than a minibus”, according to Greg Coppen, who witnessed the attack from his house on Fish Hoek beach and posted details on Twitter. Despite days of searching, no trace of Skinner’s body was found, only his goggles.

Goodbye great whites

The project has proved a success from its inception, but in the past four or five years other factors have come into play. Great whites, as has been widely reported, have largely disappeared from the shores of False Bay. On average 205 white shark sightings were recorded a year from 2010 to 2016. But in 2018 there were only 50 sightings and since 2019, none.

What’s behind the disappearance of white sharks? It is a subject of some debate, with a number of contributing causes identified, but some scientists believe the arrival of new apex predators, orcas, in False Bay, was a major factor. When orcas began frequenting the bay in 2015 white shark numbers plunged. A lack of prey species as fisheries decimate prey populations, or pollution may have played a role too.

Do we still need spotters?

No one knows if or when white sharks will return, but many find the presence of the Spotters reassuring.

Anton Edwards, a surfer, lifesaver, surf-ski paddler, and ocean swimmer, has grown up connected to the ocean. He has lived five minutes from Muizenberg his entire life. He refers to the Spotters as “a blessing”. Edwards, who surfs Muizenberg three or four times a week, said: “They [Shark Spotters] make me feel, always, kind of protected.”

He is grateful for the Spotters and the “solid shifts” they work in rain, howling winds and baking sunshine to keep him and the surfing community safe. The 25-year-old said spotting conditions can be challenging at times, especially in winter when the water is murky, but he feels safer knowing the Spotters are about.

And there is more to Shark Spotters than spotting. The project has provided work for over 40 people, mainly from the Cape Flats, where jobs are scarce and gangsterism rife. The Spotters are trained in first aid and help to educate their communities about sharks, including through the Shark Spotters information centre at Muizenberg Beach.

“One of the main reasons we need to continue spotting is the valuable monitoring work that the Spotters do. We will not know the sharks have returned if we do not have people looking out for them, and their monitoring of other marine life and activities is also incredibly valuable,” Sarah Waries, chief executive of Shark Spotters tells Roving Reporters.

Conservation awareness

Shark Spotters teach people about sharks and why we need them. As much as the attacks that killed Bornman and Skinner were terrifying, sharks do vital work. They keep our oceans balanced and healthy, by preying on other species below them in the food-chain. Shark Spotters provide factual, non-sensational information about sharks so people can make informed decisions about entering the sea.

It also supports research into questions like “Where do sharks go?”, “How do they behave in different conditions and seasons?”, and “How many sharks are there?” The organisation is involved in testing new technology that holds hope for better protecting people from sharks in an environmentally-sound way.

Sixteen years after that hurried exit from the surf at Muizenberg Beach, Bertish remains “stoked” about how things have worked out.

“I’ve always had a deep connection with the ocean and nature, and loved animals. It’s always been a big part of who I am and what I have done… and that’s how I came to start Shark Spotters,” he says.

The team, up on the mountains with their binoculars and down on the beaches with their flags and sirens are often among the first responders to crime. Over the years they’ve come to the aid of entangled marine mammals, including whales and seals. They’ve joined searches to find missing children. And the project has provided meaningful jobs and education to the community.

“The Spotters saved more people from other things than sharks,” says Bertish. DM

- Rio Button is a marine biologist, commercial diver and surfer, she has a Master of Science degree in Conservation Biology from the University of Cape Town. She is the chief conservation officer at Wildcards, a tech start-up connecting grass-roots conservation agencies with funding.

She was one of seven winners in a recent writing competition on sharks and rays run by Roving Reporters. The competition was supported by WildOceans, a programme of the WildTrust, which facilitated access to conservation-minded youth keen to share their passion and develop writing skills with mentorship from Roving Reporters. The opinions and views expressed in this Ocean Watch series are not necessarily those of the WildTrust.

Recent Comments