To understand this, start by playing with your food.

Slice off a piece of roast beef, thick enough to maintain some rigidity but thin enough to fold over with a prevailing flick. Laying it long-ways, lift one side past 90 degrees so gravity will force it towards the plated meat. With your remaining fingers, hold a pea just underneath the beef’s highest vertical edge. For added effect, scoop some mashed potatoes onto the far side of the plate. Release the flap and the pea at the same time and count how many times the pea slides smoothly down the meat. Not so often, right? Ten out of ten times, the veggie will likely fall from the sky, bounce off the meat and crash into the starch.

The beef is water, the potatoes are reef, and the pea is you. This is slab surfing.

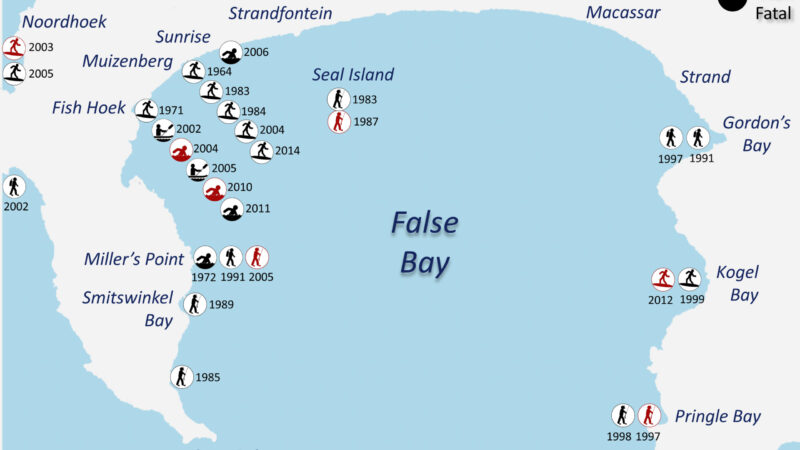

“A slab is generally a shallow piece of reef that sticks out in deep water, or deep water sits behind it,” says Maroubra’s Koby Abberton, one of the world’s most ubiquitous slab riders. “Rides are short and intense, normally running into dry reef or cliffs. At outer reefs you get bigger hold-downs and sets can catch you easier, whereas most slabs break in the same spot, so you only get cut up and break bones and get stitches. Where we live there’s a three-kilometer stretch with 10 slabs — Voodoo, Suck Rock, Boat Harbour… It all started with Shark Island.”

Shark Island, where all this slab nonsense began. Photo: Billy Morris | Lead photo: Cyclops, Jamie Scott.

In the 1970s, Shark Island off Cronulla was the nastiest slab of the day, though the term wouldn’t exist as a genre for many years to come. La Jolla, CA’s, Big Rock (or “Lobster Lounge,” a pseudonym employed by photographers of the time) and Oahu hazards like Velzyland and Waimea Shorebreak also offered slabbish potential — mesmerizing photos, gruesome injuries — but nothing like Shark Island. In 1980, Surfer Magazine assigned Peter Townend a story on the place, though like most he’d never logged a session there. PT pulled it off with aplomb, dropping understatements like: “It’s places like Shark Island that make life interesting for some people.”

Not long after, The Box across the channel from Margaret River in Western Australia saw a media groundswell when the 1987 ASP World Tour rolled through town. Ironically enough, it was Virginia Beach, VA, pro Wes Laine who led the charge, fulfilling a longtime obsession fueled by old images he’d seen of Ian Cairns. Multiple barrels and wipeouts later, Wes got intimate with the bizarre physics of this anti-wave, snapping a fin without hitting reef. By the end of the decade, a handful of nefarious Australian spots like the ragged, urchin and barnacle-encrusted Razors and the inches-deep ledge-to-sandbar Petrol Point started popping up in Seppo magazines like exposed rock, with Shark Island locals like Chris Homer dancing to the media beat — but not exactly ripping.

It took a different kind of boogie to do that.

“Bodyboarders get more than their share of bullying and exclusion at most regulation surf spots,” wrote the Evan Slater-helmed Surfing Magazine in their cover story “The Case For Slabs” (March 2006), the first American publication to spotlight the trend. “This led to a kind of Bodyboarding Diaspora…spongers left the traditional surf zones and began searching out weird, near-unrideable spots: wedges, shore-dumps, side-waves and Slabs, places no normal surfer would consider.”

Teahupoo, still in the slab spotlight many years after it was first ridden prone-style by Mike Stewart and Ben Severson in 1986. Photo: Jeremiah Klein

Before bodyboarding achieved legitimate sporting status, complete with its own pro tours and media outlets, the original face and ultimate king of the sport, Mike Stewart, was already driving the slab wagon. In fact, Stewart along with Ben Severson was the first to charge properly pumping Teahupo’o back in 1986 (although it was still known then as “End Of The Road”). As prone riders sought below-sea-level death traps as opposed to three-to-the-beach heat sealers, it could be argued that the pubescent sport of bodyboarding actually evolved quicker than surfing did in the 1980s.

“Hectic slabs can be found all over,” says Stewart, “anywhere with swell, deep water and shallow shelves, or an abrupt depth change, and new ones are constantly being discovered as our idea of ‘surfable’ evolves. My first experience with them was on the Big Island. Thinking back, this probably had a big effect on what I chose to ride. Since I first started going to Australia in the early ’80s, I’ve always thought there was amazing slab potential there.”

A visual breakdown of how Teahupoo (and most slabs) function, courtesy of Surfline’s Mechanics of Teahupoo.

As the nineties reared its well-coifed head from a day-glo sporting cocoon, back at surfing’s birthplace Westside locals like Johnny Boy Gomes enjoyed strictly enforced closed sessions at bloodthirsty Hawaiian slabs like Third Dip while Clark Little teased chiropractors in Waimea Shorebreak’s ludicrous triple-ups. By 1991, anorexic surfboards and fins-free surfing vaulted to the forefront with plenty of ballsy lensmen to record the action. Weasel Reef in Santa Cruz, CA, and Cave Rock in Durban, South Africa, were framed on mag covers while Jack McCoy films like Bunyip Dreaming kept the old favorites alive.

Shortly after igniting his first world title campaign in March 1992, Florida prodigy/Baywatch darling Kelly Slater headlined an all-star trip to The Box. Meanwhile, fellow New Schooler Shane Dorian was plunging hometown slabs on the Big Island to supplement his part in Taylor Steele’s Momentum sequel. This undoubtedly sparked new interest in slabs’ photogenic freak factor.

The Box, West Oz. Photo: Ed Sloane / WSL

Professional freesurfer Donavon Frankenreiter got exposed to Chile’s faceless holdings by national treasure Magoo de la Rosa and sidekick Makki Block — namely a chilly V-Land doppelganger called “The Hook,” and a Big Rock-ish spot dubbed “Punta Cecilia,” just south of the Peru/Chile border — destroying seven surfboards in five days. Before long, a laundry list of slabby assignments was scheduled on every editorial calendar.

Between Steele’s crew, Rip Curl’s Search initiative, and the anarchic …Lost movies, the barely rideable became totally preferable for the celluloid boom of the 1990s, as obscure weirdness throughout Indonesia and the South Pacific shared playtime with original beasts like The Box and Big Rock. Equally booming, international bodyboarding pubs regularly conquered Shark Island and other reefs that catered to their flexible vehicles and extravehicular swim fins. But few were disclosing coordinates and pseudonyms were tossed around like industry secrets.

Meanwhile, The Box became a recurring go-to trip for swell-chasing pros. In fact, by 2000, Surfer still listed it as one of the world’s ten most dangerous waves alongside Shark Island, Third Dip, Waimea Shorebreak and a terrifying Tahitian spot that completely changed the game of slabbery. As “End Of The Road” morphed into the more exotic-sounding “Teahupo’o,” so commanding was its allure, the ante was upped overnight. A surf magazine was not a magazine, a surf movie not a movie, without a requisite “Chopes” part. The fascination permeated every level of surf consciousness until the ASP finally threw their hands up and instituted a WCT contest there in 1999, the Gotcha Pro Tahiti.

Cory in ’99, Laird in ’00, Andy in ’02, Dorian in ’07, Nathan in ’11 (above), Nate in ’15… Teahupo’o has produced so many watershed moments it might’ve indeed been the end of the road for slab seekers. But even with Pipe still holding court as the most photographed, and most lethal, wave on Earth, and Chopes chargers pushing the limits to unfathomable degrees, competing magazines sought international variety to stay ahead of the curve.

“Once a slab has been published,” says Surfline Senior Photographer Jeremiah Klein, “the bar has been set and it needs a bigger swell or to be documented differently to catch the public eye. A perfect example was 2011’s Code Red swell in Tahiti. Would Nathan Fletcher’s wave have made so many covers if it were any smaller? No, because Laird already got that cover years ago.”

Seeking to broaden their appeal with more than Chopes swells and Indo trips, a reverse Cold Rush ensued — Scotland, Canada, Madeira — revealing sketchy potential everywhere while neoprene technology improved and PWCs became a semi-permanent part of the equation.

Meanwhile, the American bodyboarding industry became a canary in the mine for economic recession, but their culture thrived outside American airspace. “Back when I was working for Bodyboarding Magazine,” remembers Klein, “it was all about finding slabs because they were the most photogenic to shoot. The Australians were years ahead in finding unsurfable waves and making them surfable. Australia is the slab capital of the world because their surfers are hungry for it.”

The Tasmanian Devil now known as Shipstern’s Bluff. Photo: Stu Gibson

So it only seemed natural that the search would return to Oz, in particular, Tasmania. In his Surfer story “Tackling The Tasmanian Devil” (Winter 2001), Ross Garrett dubbed a grotesque, boil and step-laden righthander “Dead Man’s” before tribesmen settled on “Shipstern’s Bluff.” Coincidentally, that same issue featured a trip to Lanzarote’s “The Slab,” the first officially named so.

Readers barely had time to digest that term, much less settle their stomachs from Shipstern’s swallowings when, less than two years later, Bill Sharp’s supercharged Billabong Odyssey crew of Mike Parsons, Brad Gerlach, Layne Beachley and Ken Bradshaw found an even scarier monster in South Australia. They named it “Cyclops” after the mythical creature in Homer’s The Odyssey, though the spot had previously been known as “Greg’s Knoll” after its founder, a nutty abalone diver.

A return trip to Cyclops in 2005 by the Abberton brothers, Mark Matthews and photographer Andrew “Shorty” Buckley confirmed what the Americans had suspected: This had to be the meanest break on Earth. In fact, after two sessions, numerous dances with death, and 35 stitches between the two of them, Koby reckoned it wasn’t even a wave while Mark vowed never to return. “Cyclops is the most dangerous there is,” says Koby. “But slabs are everywhere. It just comes down to what really is a wave.”

Surfable? Some think not. Cyclops, Australia. Photo: Jamie Scott

While another slab resembling a coldwater Teahupo’o was kept from being unearthed along the Victoria/New South Wales border, Maroubra surfers didn’t bother with clandestine details of what they’d found in their front yard. They simply named it “Ours” and showed it to the world via the award-winning documentary Bra Boys — any viewing of which quickly dissuades any glory-seeking outsiders.

On March 4th, 2006, 19-year-old tow rookie Laurie Towner took slab-slaying to another realm when he paddled into maxing Shipstern’s, even outshining veteran Billabong teammates Joel Parkinson, Andy Irons and Dylan Longbottom for a mind-blowing section in Billabong’s grommet DVD Frothing. Shortly after Towner’s megalithic plunge, the aforementioned Surfing piece popularized the craze before the dial wandered toward Chile for yet another milestone in Slabdom: a WCT contest.

“El Gringo” set the stage for the Rip Curl Search Arica (2007), which dished out one of the heaviest pain tallies in professional surfing history: stitches, concussions, urchin spines in the face, mussels in the ass, vomiting, board destroyers and rock dances that were as painful to watch as they were to walk. Many competitors called it the heaviest waves they’d ever surfed, easily comparable to Pipe or Teahupo’o in terms of consequence.

The next year, Mick Short was emblazoned on the front page of Surfer for their cover story “Drag-In Slayers” (December 2007), which focused on Down Under’s most ravenous depth chargers: “In today’s surfing world, altitude no longer suffices as a barometer for ‘bigness’ but rather than height, sheer mass has emerged as the paramount wave feature. How many times overhead no longer matters; rather how thick, how hollow and just how deadly.”

The writing was on the wall, and painted in blood. New stars emerged instantly — some simply for eating shit and surviving catastrophe. After all, they had new mechanics and circumstances to negotiate — like “get the first wave of the set because the second won’t have any water on the reef.”

But just when it looked like the Aussies had a lock on this uniquely masochistic pursuit, Surfer photographer Jason Murray brought a top-shelf crew of Hawaiians and Californians to the Pacific Northwest in Fall 2008 for a date with “The Yeti,” which was cold, localized, sharky and so shallow Garrett McNamara’s face required 15 stitches after he kissed the urchiny reef. From Murray’s photos, The Yeti looked even slabbier than other slabs.

Silverbacks, Bocas del Toro. Photo: Jeremiah Klein

Or not. The scale was being distorted so quickly: Central California, Brazil, Micronesia, Morocco, Taiwan, “Galicia Slab,” “Silverbacks,” “The Right”… Suddenly which slab was which became more confusing than a two-tiered world tour or whatever kind of grab Dane was doing.

But as slab militias waged their scattered, strategic assaults a quiet, wholesome lad was conducting solo experiments half a world away from everyone. And wouldn’t you know it: he took his lessons from bodyboarders, plus a uniquely enlightened mentor who happened to be a photographer, filmmaker and keen waverider.

In the February 2011 issue of Surfing Magazine, Taylor Paul painted the picture of this unlikely product of 21st century technology and self-sufficiency in “Fergal, Of Ireland,” which detailed Fergal Smith’s rise from Ireland scout-about to ambitious big-slab surfer to branded professional athlete — the ultimate country boy success story. Fergal also earned a part in the Transworld Surf movie High-5, which according to TWS constitution only five surfers make the cut for. All of Fergal’s rides were shot at his gorgeously lit, frighteningly thick Irish studio. “Besides a handful of bodyboarders there was nobody for me to learn from,” says Fergal. “It wasn’t until I met Mickey Smith that I really began to learn what riding slabs was all about. The buzz from riding one is like no other.”

Those same slabs facilitated his career while affixing a bullseye on Fergal’s larger homeland. Given its unique topography and exposure, the U.K. and Ireland could be the next slab-rich frontier to follow Australia. “It’s not all been roses for us though,” Fergal warns. “Tom Lowe broke his foot a few weeks back and dislocated his shoulder twice. Mickey snapped his arm. Another smashed his kneecap in seven places. Another mate broke his whole face and had plastic surgery. One guy broke his back. I smashed my face in, 16 stitches. The list would go longer if I were to name all the injuries here.”

Which brings us to the elephant in the room: Why don’t more people die riding slabs?

“I ask myself this question every time I surf a slab,” says Koby. “Ours has broken three backs this year, but for what goes on out there every swell, that’s nothing. There should be a lot of us dead.”

Leave it to the original slab hunter to have an opinion on the matter.

“Most tragic surf accidents happen in heavy, hollow surf,” says Mike Stewart, “so this is sort of a misnomer. You could say that there should be a lot more maiming and death, though, and I have a number of theories why there aren’t more. One: Surfers challenging themselves in these types of waves have more skill at riding and wiping out and, as a result, can cope better with critical predicaments. Two: Thick, heaving pits can be daunting, which causes people to get into fight-or-flight mode. Fueled by adrenaline, senses are heightened and the body’s ability to cope with these stressful behemoths improves. Three: Slabs are very shallow, and water doesn’t compress well. As a result, I believe there’s a ground effect. As a thick lip unloads on a shelf, the water doesn’t have anywhere to go, so it will almost always have a layer of water to dampen impact, so long as the slab is underwater.”

“But should you get impaled,” Mike digresses, “don’t blame me.”

“Most tragic surf accidents happen in heavy, hollow surf,” says Mike Stewart, seen here at Pipeline. Photo: Henrique Pinguim

Stewart needn’t worry, as only a few truly possessed souls with spines of steel, balls like boulders and maybe a silly star chromosome will go looking for these things.

“Slabs bring back the stoke in surfing,” says Koby. “You’re usually only surfing with people you know. Instead of surfing a beachbreak with 50 people you’re getting tubed off your head with five friends. All these slabs are 20 feet from the rocks. You can hear the surfers talking and teasing each other. There’s blood and guts. At Ours or any other crazy slab in the world, the crowd is rooting for you. They watch as you come in and tell you it’s amazing. If they see you get thrown against the rocks, they’re ringing the ambulances, as they know you got hurt. They’ve seen it. They’ve heard it. And they can’t believe you’re alive. It’s exciting.”

Exciting? Absolutely. But is it fun? The truth is most surfers will continue to draw inspiration from those cliché “wave sketches in their schoolbooks.”

Only a mad few will play with their food.

Another (and more recent) mutant moment in slab history: the Red Bull Cape Fear 2016 held at Ours. No takers on this one. Photo: Brett Hemmings / Red Bull Content Pool

Expert forecasts

Surfline’s team of meteorologists provide detailed forecasts for thousands of breaks around the globe. Start your free trial to Surfline Premium and we’ll help you know before you go.

Recent Comments