Consider the surfer:

Credit: Eric Pinczower ’82

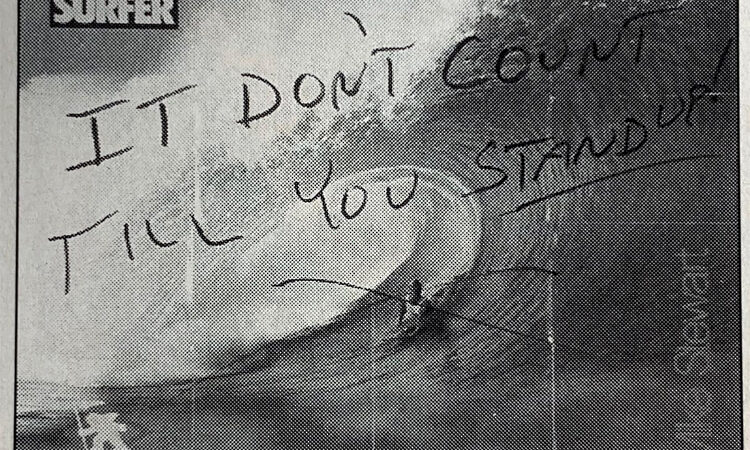

Polynesian originator, fun-in-the-sun enthusiast, counter-cultural vanguard. That’s pretty much how things went for the image of the wave-rider, from surfing’s inception all the way to the early 1970’s, when young practitioners started routinely shunning the establishment and ditching class left and right. Once Fast Times at Ridgemont High hit theaters, it simply catalyzed a freshly gelling reputation — surfers, as far as the general public could tell, now held ground somewhere between pathological deadbeats and brain-dead hippies. The slightest whiff of surf association got you socially and intellectually pigeonholed in the back of Spicoli’s van. To society at large, surfers and rocket scientists occupied opposite ends of the spectrum. All I need are some tasty waves, a cool buzz, and I’m fine — said no one in a lab coat, ever.

Luckily, stereotypes meant little to the surf-scholars who entered UC San Diego in the late 70’s and early 80’s. There were only two things that mattered to this independent-minded lot: access to a great education and access to great waves. That’s it.

Credit: Mark Johnson ’88

Our campus was ideal because just down the cliff was one of the best surf breaks in California — Black’s Beach. There is well-known bathymetry at work there, mostly due to the ultra-deep Scripps Underwater Canyon, which funnels larger and better-shaped waves toward Black’s more than anywhere else in Southern California. Instead of dreaded close-outs, Black’s is famous for producing powerful and bowly A-frames, beautifully tapered two-way waves perfect for aficionados. With the freshman dorms just a short hike away, UC San Diego was a backstage pass to this coveted phenomenon, and still is today.

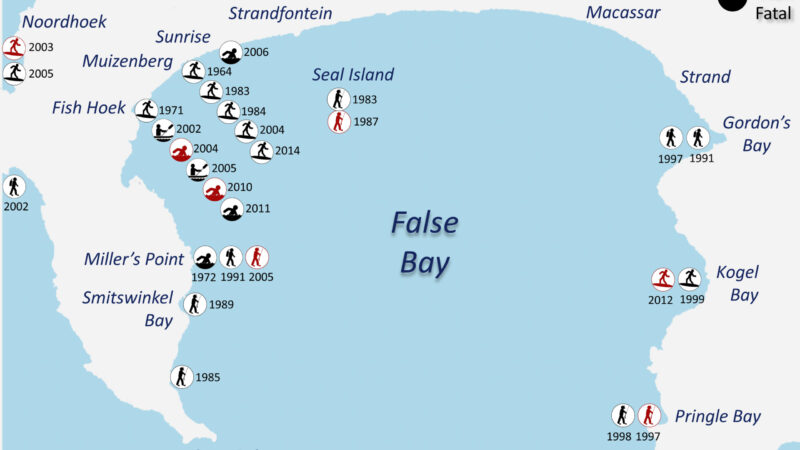

One of the first groups to take full advantage of this stellar surf/academic duality was the freshman class of ’79-’80. Despite academic priorities, most of these undergraduate wave riders scheduled courses with surf time built in. A typical day might involve a morning session at Black’s, followed by a few classes back-to-back, followed by another hike down to Black’s for the evening glass-off. As these students soon discovered, Black’s is an education in itself— presenting multi-faceted lessons in time management, courage, discretion, and humility. In surf terms alone, Black’s involves a difficult paddle-out, a complex lineup, and unusually heavy beatings. Even for experts, it’s quite possible to drown there. You add to this experience a steep, heart-pounding cliff negotiation, an abnormal abundance of sea life, thick, aggressive surf crowds, sub-60-degree water temperatures, groups of creepy nudists, and well … it was a radical school of another sort.

Black’s wasn’t just a great training ground; it also provided a social framework. Inevitably, you’d see the same faces doing the same beach-school-beach loop, and this familiarity usually led to conversation and bonding.

How rad was that morning session?

Credit: Mark Johnson ’88

By mid-fall, most of these surfer-students already knew each other, and any awkwardness had dissipated like an outgoing tide.

Which might help explain the atmosphere in a Revelle College classroom one evening in October, 1979. At the given hour, a curly-haired, smiley graduate student by the name of Michael Shand, M.A. ’75, Ph.D. ’80, stepped in front of a group of abnormally tan and thoroughly relaxed young men and women and commenced to sell the group on becoming part of an official UC San Diego surf team, with himself as coach.

A surfer himself, Shand knew his pitch needed to be delicately balanced, catering to the authority-suspicious, bohemian DNA strands embedded in all wave riders. So he started things off with a bang: a fully sponsored 10-keg beach festival, an Isla Vista blowout Halloween weekend, and an adult film fundraiser.

Having captured the group’s attention, Shand launched into details on the competitive season. The team would travel up and down the coast for bi-monthly contests to be held at venues like Huntington Beach, Ventura, Mission Beach, and Santa Barbara. Other colleges on this recently sanctioned circuit included SDSU, USD, Orange Coast, Saddleback, Golden West, Pepperdine, and UC Santa Barbara. There would be three divisions: men’s, women’s, and knee-board, with try-outs and practice contests to be held at Black’s, of course. With an A and B team structure, no one got cut — if you showed up, you made the squad. Lastly, there was just enough in the near-term budget for team t-shirts.

With that, the season began to play out. The Triton team narrowly lost the first contest to Golden West College, but rallied from there. A little more practice and surfing mock heats together was all it took — the group learned to maximize 15-minute heat times and exploit the roster depth. More importantly, with the time spent together, the group bonded with a fun-above-all-else attitude. This led to a sense of relaxed positivity, which, in turn, led to confidence. As far as the group was concerned, winning was great and all, but it was just the cherry on top. Hitting the road together as a like-minded, happy-go-lucky, ocean-addicted entity—that was the real win. As such, contest road trips became a reward within themselves. And while other colleges could occasionally match the talent of the top one or two Tritons, they would eventually fall prey to UC San Diego’s multidivision cohesion. Some of our standout winning machines included Mark Brolaski ’82, Craig Schieber ’85, Steve Colton ’83, Isabelle Fried ’84, and Bill Lerner ’84.

Credit: Robert O’ Toole

From there, the team finished the rest of the season with a 10-4 win/loss record, then narrowly lost a national title shot at a single, post-season event. The writing on the wall was clear, however — a National Championship was inevitable. The following year, the team continued to ride their momentum and went through the regular season undefeated, and with additions to the roster like Peter Curry ’86, Matt Robertson ’88, and Mike Glevy ’89, the Tritons won the National Title two seasons later in 1983.

1983 was an appropriate year to win a national title, as El Niño brought gigantic surf to our shores. No other team on the coast had to consistently face (or attempt to survive) such challenging conditions as those found at Black’s that year. Man, how sketchy was it out there this morning? As such, a national championship was a fitting and well-deserved reward.

Yet because the Nationals were held at the end of the school year, few UC San Diego students or members of the administration ever became aware that their school had risen to number one in the country. By the start of the fall quarter, it was old news. Surfers aren’t really the kind to brag about their achievements, either. In the surf world, in fact, drawing too much attention to yourself and “claiming” a performance is generally frowned upon. It’s known to be considered bad style.

Which in no way should diminish the accomplishment — with no recruiting, a tiny budget, and the toughest academic workload of any college participating, UC San Diego was the number one surf team in the nation during one of the biggest years of Pacific surf ever measured… it’s something to be extremely proud of.

Even if most of the campus was oblivious to the team’s accomplishments, word had spread within the surf community. A premier university with a premier surf team and access to a premier surf spot became a self-fulfilling prophecy — it drew the attention of talented surf-scholars from around the country and helped build an even stronger group in subsequent years.

How sick would it be to surf for a school that’s right on top of Black’s?

Any College-bound surfer worth their salt asked themselves that, and aspiring pros like Allen Johnson ’90, Kent ’97 and Bryan Doonan ’96, and Sean Hayes ’97 eventually joined the likes of uber-rippers like Isabelle Tihyani ’89, Jack Beresford ’88, Mark Weber ’94, Jason Burns ’95, and Amber Puha ’93. And perhaps no individual embodied this pilgrimage more than Evan Slater ’94 — a high school senior in Ventura, Calif., who was not only Men’s National Surfing Champion but held a 4.17 GPA. Recalling his potential college choices, Slater reflects, “UC San Diego was my first and only choice from the beginning. I would have turned down Harvard to spend my formative years at the best surf college on the planet.”

Credit: Lonnie Ryan

Such allegiance made the Triton surf team a national powerhouse in the late ’80s, ’90s, and early 2000’s. By 2004, the university had won six national championships. Over the course of these years, however, things had started to change: the kneeboarding division was supplanted by bodyboarding, liability and red tape issues multiplied like rabbits, and other schools like Point Loma Nazarene, USC, UCLA, MiraCosta, CSU San Marcos, and Cal Poly joined the circuit. The most significant difference, however, was how other universities began to see the light and take their surf programs seriously. Recognizing the surf aura as a powerful recruiting device, beach-adjacent universities with successful and supported surf programs could potentially attract — and keep — students who wouldn’t have otherwise considered them.

Conversely, this is right about the time UC San Diego’s surf program began to stagnate. Stratospheric academic requirements, administrative ambivalence, and a growing reputation as a social desert took its toll. The university started to fall lower on prospective surf-scholar lists, while other, more proactive universities began dominating contest seasons and siphoned away talent. The Tritons suddenly found themselves in the rearview mirror, and although they fielded extremely talented surfers over subsequent years, like Garth Engelhorn ’03, Shaun Burrell ’13, Mike Ciaramella ’15, Holly Beck ’01, Kokoro Tomatsuri ’13, Max Hoshino, MD ’07, and Lauren Sweeney ’08, they haven’t won a national title in the last 16 years.

Credit: Nikki Brooks

“Championships are won by having a depth of talent in the roster, and recruiting that talent takes support — from the university, as well as from former team members staying engaged and involved,” says Tyler Callaway, the current surf coach who’s officially led the team since 2003. The bigger picture Callaway alludes to is a multi-point case for strengthening and expanding the UC San Diego surf program: For starters, there is the inherent social framework in surf culture which, if allowed to thrive and spread, could greatly elevate the student experience. Secondly, surfing today is a multi-billion dollar industry in need of intelligent, surf-experienced college graduates. Third, and perhaps most befittingly, are the many scientific and research tie-ins to be had within the burgeoning field of surf science, which includes topics such as wave-generated renewable energy and climate-crisis wave forecasting. Bringing this potential link to the university’s attention is something of a personal mission for Callaway, who sees it as a route to attracting top talent and restoring the surf team to its former dominance. “Surfing has been a part of San Diego’s culture for over 100 years and part of UC San Diego’s for 50,” he says. “Many surfing alumni have expressed support for the development of more surf science curriculum. I’m embracing that cause because I believe it has many potential benefits for the school and the San Diego community. It speaks to a San Diego ethos of success: Do what you love, work hard, play hard.”

Credit: Mark Johnson ’88

And on the topic of success, it’s worth noting that those six national championships make the surf team one of the most successful sports organizations in UC San Diego history. Better yet is the record of success that has followed surf team alumni — the roster of the ’79-’80 team alone produced two surgeons, four engineers, an attorney, an environmental scientist, a linguistics professor, a biotech CEO, and an award-winning photojournalist. In the years since, the team has produced museum curators, marketing directors, apparel magnates, doctors, surgeons, teachers, investors, software engineers, biochemists, and business owners large and small.

It is with no shortage of irony that a lifestyle once considered the sole province of bums could be brought so far from a stereotype. But that’s UC San Diego, where the Pacific washes all things anew. And truly, there’s no better poster child for this sea change than Jared Lang ’08, an astrophysics major who rode for the team from 2005 to 2008, and went on to become, you guessed it … a rocket scientist.

Contribute your own surf stories and photos on the Surf Team Google Doc!

Take a look at more photos from Rob Gilley ’84 on Flickr.

About the Author:

While recovering from major back surgery, writer/photographer Rob Gilley ’84 picked up a copy of Triton magazine. “I was reminded of my time at UCSD and the years spent surfing at Black’s Beach. Researching this story, reliving old times, and reconnecting with old friends not only brought me out of my post-surgery funk, but is helping me get through a pandemic.

Recent Comments