There’s a warmth in Len Webber’s voice, and for good reason. He has a second chance to do something good.

Next week, when the House of Commons resumes sitting for the first time since mid-December, the Conservative MP for Calgary Confederation will again introduce a private member’s bill that aims to increase the rate of organ donations in Canada.

It will be a carbon-copy of a no-fuss bill he tabled in the last Parliament that sought for Canadians to be asked on their income tax returns if they consent to becoming organ donors. The data would then be sent to provincial and territorial governments to update their donor registries — a simple tweak that Webber thinks will help save lives.

Watch: Len Webber introduces organ donations bill in 2016

Webber’s bill passed unanimously in the House in 2018, a rare feat for any MP, let alone an opposition member staring across the aisle at a majority government. Liberals even set aside $4 million in a fall economic statement for the Canada Revenue Agency to implement the change.

Though the idea was uncomplicated, the same can’t be said for the gears of Canada’s political system. Webber’s bill ultimately died in the Senate when the upper chamber wrapped its business in June ahead of the fall federal election.

“Of course, it was quite disappointing,” he told HuffPost Canada.

The system has its quirks, too. At the start of each new session of Parliament, the House Speaker holds a lottery to decide the “order of precedence” for private members’ business, the bills and motions tabled by MPs who aren’t in cabinet or serving as parliamentary secretaries.

“It’s basically like drawing names out of a hat,” Webber said.

With a bit of good fortune, an MP whose name is drawn early is assured enough time in the parliamentary calendar to put something up for debate. It’s tougher sledding for those whose names are drawn later, which is why MPs try to trade spots with colleagues in better positions or lobby the luckier ones to take on their pet project.

‘My first thought was some kind of… divine intervention’

Webber said he went to the December draw to “see who I could target to take on my bill so that it would pass.” There would be no need: Webber’s name was pulled first.

“Honestly, my first thought was some type of… divine intervention,” he said.

And he couldn’t help thinking of two people who would have been delighted by it all.

The first is his late wife, Heather. She was diagnosed with stage-four breast cancer at the age of 37, and it spread throughout her system. She died after 10 years of chemotherapy and radiation, leaving behind three daughters.

Webber was a Progressive Conservative MLA in Alberta at the time and said the experience of loving and losing someone so precious altered how he looks at life.

“It certainly changes your outlook on life and what is and what is not important in life,” he said. “What is important, of course, is to live life to the fullest and work for causes that you feel strongly about.”

In her last days, Webber’s wife lamented she could not donate her organs, as is common for those suffering with a spreading cancer. Her advocacy on the issue — that yearning to help others — stayed with him.

Bill Graveland/CP

Webber introduced a bill in 2013 that sparked the creation of the province’s first organ and tissue registry. It’s an accomplishment Webber said came together with the help and counsel of Robert Sallows, a local organ donor advocate active in conservative circles who helped lobby MLAs on the issue.

Sallows is the second person Webber believes will be smiling down on him. This bill, like the last one, is dedicated to him.

A double lung recipient, Sallows died in 2018 at the age of 31, about a week after Webber’s bill cleared the House.

Sallows’ mother, Kathy McGillivray, said her son “adored” the MP, that they just had one of those special connections in life.

Sallows was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension at age nine, a condition that severely restricted blood to his lungs. After years of various medications and an IV-pump that went right into his heart, he was listed for a transplant at age 16.

The call finally came after a year on the transplant list, an experience McGillivray called surreal.

“I just want everyone who is on a waiting list to experience that thrill, that anxiety, that excitement,” she said.

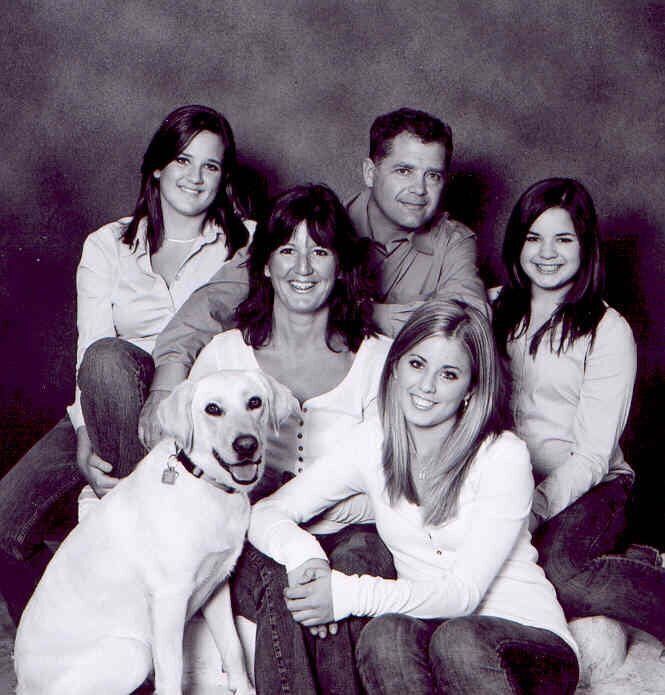

Courtesy of Kathy McGillivray

McGillivray remembers the 2 a.m. drive from Red Deer to the Edmonton hospital where her son underwent surgery. She remembers the people pouring out of bars as if to greet them on their journey, the Christmas lights that were still shining in early January.

“I remember looking at the sky. And it was the clearest night,” she said. “And I’d never seen so many stars.”

Within a year of the transplant, Sallows ticked off three goals he set for himself: to finish high school, to get a driver’s license, and to go wakeboarding with his friends.

But in 2017, doctors discovered cancer in Sallows’ small intestine, something totally unrelated to his other health challenges.

“He was special that way. If it was rare, he tended to get it,” she said. “We never in a million years thought cancer would get the better of him.”

McGillivray doesn’t know who donated the lungs but quietly thanks that person everyday for the gift that was given to her family. Sallows was able to donate his eyes after his passing in 2018.

Courtesy of Kathy McGillivray

McGillivray thinks her son — ever the politics buff — would be thrilled and “absolutely honoured” that his name will be spoken out in the Commons when Webber’s bill comes up for debate in February.

Webber isn’t expecting any opposition to his proposed legislation. It’s a “no-brainer,” after all. But he is looking forward to debates that he hopes will “drum up conversations around dinner tables” about the importance of registering to donate and about each person expressing their wishes in the event they suddenly pass. According to data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information, 223 Canadians died waiting for a transplant in 2018.

It is not lost on Webber that he essentially gets to kick off a new parliamentary session, one that will have no shortage of things about which politicians can fight, with something that can be “unifying.”

“We can all be a part of providing Canadians with good legislation and we call all agree upon it,” he said. “We don’t always have to necessarily disagree with one another.”

If all goes to plan, Webber thinks his bill could be before the Senate within two months. In March, he’ll mark 10 years since his wife’s death.

“If any politician can change one thing for the better in this world… they’re not going to change the whole world overnight but… if you can just do one little thing that improves the lives of Canadians, then you’ve done your job,” he said.

Recent Comments