This article is part of a series called “How to Human,” interviews with memoirists that explore how we tackle life’s alarms, marvels and bombshells.

Newly divorced and edging further into her 40s, Diane Cardwell’s life hadn’t turned out as planned. So one day, out on a reporting trip for The New York Times in Montauk, a beach town at the eastern end of Long Island in New York, Cardwell seized the opportunity when a cottage rental and surfing lesson presented itself.

The result was the first step on a long journey that took her from a version of her life she’d always imagined — the house, the career, the husband — to another version in which she found joy and love again, complete with a new community of friends and a house in Rockaway, a surf town — yes, a surf town — in New York City.

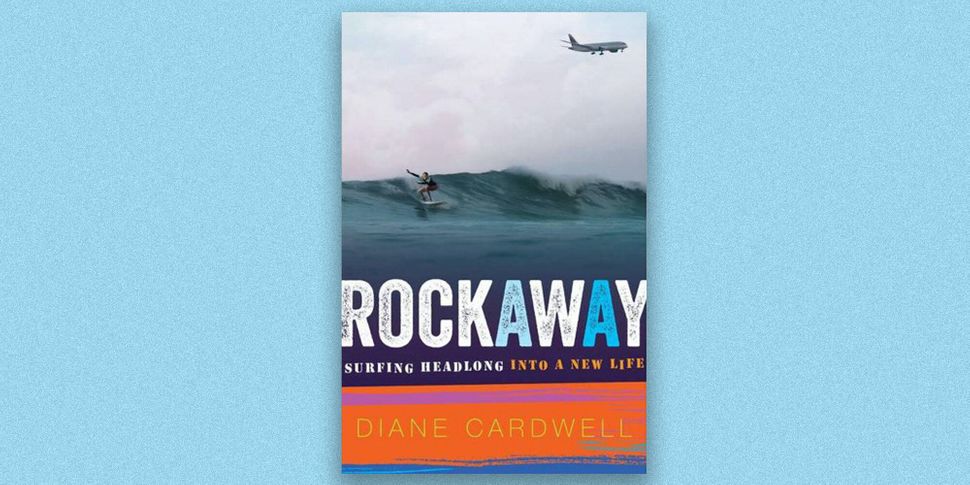

In the spirit of “Wild” by Cheryl Strayed and “Eat, Pray, Love” by Elizabeth Gilbert, Cardwell sets out on a journey to learn to surf and comes to the end of the road a changed woman, transformed by her experience. The result is her memoir, “Rockaway: Surfing Headlong Into a New Life.”

HuffPost spoke to Cardwell via a Google Hangout early in July.

This interview was condensed and edited for clarity.

Tell me about the seed of this memoir. What inspired you to write it?

I wrote an essay for Vogue after Sandy, and I just got such a tremendous response from it. I wrote the essay during the first, I don’t know, three or four days after the storm. I was in a fugue state. I didn’t know how I was going to help replace my utilities that were gone. And when the editor called and he was like, “We can pay you,” I was like, “That’ll buy a new boiler.” So I ended up doing the story and I was actually very grateful to do it.

So that was the first inkling that maybe I had a subject that might interest people. I mean, I literally had strangers coming up to me on the beach like, “Oh my God, it’s so great to see you back in the water.” And, “I love that story.” And then a couple of years later, I think in 2015, I did a story for the style section that actually yielded the subtitle of the book; the headline was ”Surfing Headlong into a New Life.” That was the piece that showed me that I had an arc, a beginning, a middle, and an end— and even a happy ending where I’m finally able to surf, at least reasonably decently on good days. And I was in love and had this life that I couldn’t have imagined even three years later. So that was how I got to writing the book.

Houghton Mifflin Harcour

Surfing is not something you just pick up and know how to do. It’s a huge undertaking. It boils down to practicing it over and over. There is a scene in “Rockaway” where you and your friend undertake a month of practicing every day: He practices writing and you practice surfing. Could you talk about that?

Right. So I think, well, with surfing specifically, you stand on the beach and you watch good surfers in the water and it looks incredibly easy — and I’m talking about normal-sized surf, not those enormous skyscraper-high waves — but then when you try to do it, it’s actually really hard. And I think some people, especially if they start much younger, it can come really quickly. Their bodies are more flexible, they pick up new things. But surfing isn’t really like that and was really, really not like that for me. I mean, I think of myself as the anti-natural.

I just could not do it for so long, but I loved it. And so I knew that the only way to get even a reasonable competence was going to be to practice. And that month was pivotal for me in a way, because I had this friend who wanted to try to write; I was trying to surf. He said, “What if you were to surf every day? And what if we were both to keep each other honest, and report back?” That kind of accountability really helped me stick to it, because I didn’t feel like getting in the water every day.

I would get up and say, “Oh, it’s cold.” Or, “I’m tired.” Or, “I just want to sit out back in the garden and have a beer.” But it became a thing that I had to do. And so the day was organized around “When am I going to surf?” I think that that kind of practice, and also accountability, is important in anything that you want to pursue in a serious way. And that doesn’t mean that it’s ever going to be something that’s your career or something that you do to the exclusion of other things. But if you want to do it seriously and get the benefits of doing something seriously, then it just takes attention.

I wasn’t aware of quite the journey I was embarking on when I embarked on it. I didn’t really think, ‘I am going to solve my life now.’ Diane Cardwell

What’s your practice like nowadays?

So I’ve not been surfing recently because of COVID. But I am just starting to get back into the swing of things now that I feel a lot more comfortable that you’re unlikely to get the disease from outside casual contact at a surf break.

I do try to do something for my surfing every day, whether it’s yoga or practicing pop-ups in the living room, or strength training, stuff like that. But the truth of the matter is the best practice for surfing is surfing. And so, I’m just trying to make myself get back in the water as many days as I can.

One thing I really enjoyed about your memoir is it’s very reported, in a super nerdy fashion. You write about the physics of waves. Tell me about that.

So, I am just kind of a geeky, nerdy person, always have been. I’m fascinated with how things work, even though I’m not very adept at understanding. I don’t have a very good head for numbers or for physics. I never took physics. But I can get the concept, and so I was just fascinated because I was spending so much time in the water, looking at it, trying to feel how it was moving and understand the way the waves work that I just started wanting to know more about what was going on physically.

I was also looking at historic surf writing. I just wanted to know what that canon was, and that’s how I came across Jack London, who had what I thought was the most eloquent description of how a wave forms and what happens when it breaks.

His description of how water doesn’t actually move, but molecules agitate.

Right. It’s a communicated agitation. It’s energy passed from one particle to another. And I was just like, “Jack London, yes.”

The parts where you write about the history of surfing were so fascinating to me, like when you go into the Lenape tribe summering in Rockaway hundreds of years ago.

Yeah. Well, so I knew some of the history, and then a lot of it I had to learn more about to write the book. But when I came across that fact, that the Lenapes would make summer camps here and then move inland in the fall and winter to harvest crops, and then be closer to forests with small game, I was like, it’s always been a summer destination. For the earliest New Yorkers, it was a summer destination. And so the idea that that’s how people have been using and treating this place, that’s the relationship that the city has always had with it, it was just amazing to me. And then, just learning how incredibly grand and fabulous Rockaway was. Astors and Vanderbilts coming out.

Changing your life in your 40s seems like a Herculean task. Your book reminded me of the journey genre, like “Wild” and “Eat, Pray, Love.” Is that something you thought about as well? Could you speak to that?

Yeah. So, I wasn’t aware of quite the journey I was embarking on when I embarked on it. I didn’t really think, “I am going to solve my life now. I am finally going to crack the code on happiness for myself after all these years of not quite being able to do that.” All I thought was this pursuit and being in this place makes me feel really good, so, I should continue doing that.

I had had a little bit of that experience after my divorce when I took a photography course in Italy and literally was rolling around on a riverbank, like, my shirt in the mud, trying to figure out how to slow down my shutter speed and make the water look milky. And I realized — I was like, “Oh my God, I’m happy.”

And it was the first time that I had felt this kind of pure joy since my marriage had fallen apart. And so that was the feeling. And then, I pursued photography a little bit and that was really great and meaningful, but the surfing was different because it also gave me a way to interact with people and meet people.

And so I think it’s difficult to take on transforming your life as my project is transforming my life. I think what works better is if you just pursue something that makes you happy and see where that takes you. It’s like if one of my friends who I quote in the book said, “Do what you love and you will always attract the right people into your life, and the rest will all fall into place.”

I just think adult education and hobby pursuit is just really, really important and just a great way to get to know people and rebuild your community.

On top of that, you conducted this transformation in middle age, when our bodies are just naturally becoming weaker. I love that you turned the middle-aged woman narrative on its head. Could you talk about that?

That is true. When I started coming out here, I noticed, one, there were a lot of middle-aged surfers out here, and two, I fell in with a group of women of all ages, from their 20s to their 40s, in surf class. And everybody was struggling. Most people were not struggling quite as much as I was struggling, but everybody was really supportive, and we had great instructors who were just really encouraging. And so, with that support network, it was pretty easy to keep at it.

And also, it was just so much fun. That’s the thing. Because part of what’s great about surfing is that you don’t have to go for every wave. So you can pace your session yourself if you’re not in a super crowded break where you’re only going to get one opportunity and you got to take it.

So, there were periods of rest in between your incredible activity, but also you just get to actually sit in the water, feel the ebb and flow of the current and the waves, and see the sun sparkling off the water, maybe notice a stingray going under your board or a pod of dolphins. And so it’s a total cosmic experience. So yes, it is very physically challenging, but not every instance of it is physically challenging.

One thing that is so hard, also in middle age, is finding community and finding new friendships. You were coming from a place of divorce, where you had a previous community, and so do you want to talk about that transition and what that’s been like as these friendships have probably blossomed by now?

I think, again, part of it is if you have an activity that brings you into contact with other people who like that activity too, it just makes it a lot easier to connect. And the connection ends up being, can be light and bouncy and not necessarily become one of your best friends in life, or it can. It can be really, really profound, and you can find a new best friend or a soulmate or what have you.

And I think that’s as true of surfing as it is at any other pursuit. It’s like, if you like to draw, you can probably make a community of friends out of people who also like to draw, whether you meet them in some kind of online situation, whether you meet them in an art class.

I mean, this was one of the things that I realized coming out of the divorce is that I just think adult education and hobby pursuit is just really, really important and just a great way to get to know people and rebuild your community. Because even though I had a quite amicable divorce, it’s like, some of those friends just fall away. It’s inevitable.

You came to surfing as a super successful reporter, having received major journalistic accolades and working at The New York Times. And then you took up a sport in which you had to fail regularly, in which failure was just par for the course. Let’s talk about that.

Well, I will say, it’s just hard, right? It’s just, it sucks sometimes, and actually it sucks a lot of the time. And I continue to wish that I were a better surfer, [that] I could really just nail that pop-up. And because I’ve actually gotten halfway decent at riding waves once I’m on them, it’s just getting to my feet that’s such a challenge.

But I think there are a number of benefits to having been so lousy and had to struggle so much. And one of them is that I really did learn to focus on the experience rather than the result and to take some measure of joy out of the experience rather than just the result. And also to just learn how to be more patient with myself and not care so much about whether I was being quote-unquote “successful” and just enjoy the fact that I was there and that I could do some things that I couldn’t do when I first started.

There’s such a nice scene where someone tells you that they’re really proud of you for having caught a wave. I got super teary-eyed reading it. I think that so much of your book is you kind of beating yourself up a lot about not being able to get to where you want to go in surfing or feeling like you got to the sport too late. And I was wondering if you feel like you have finally gotten through to the other side. Are you proud of yourself?

I would say I’m definitely proud of myself for having stuck with it and having been able to kind of, as I say, talk myself out of being so afraid to fail that I cut myself off of things that I want to do. And so, there is some pride, but also gratitude, right? That was my teacher in Costa Rica. And that moment, that wave really did make me feel like I can do this and I should keep trying. And I went back to Rockaway and was terrible all over again, but I had the feeling of that big, beautiful wave in my head and I felt, I kind of knew, and that really kept me going.

Recent Comments