[We’re excited to announce we’ll be showing The Endless Summer and The Endless Summer II at the Wavelength drive-in cinema, overlooking Watergate Bay, on the 15th and 22nd of August respectively. Get your tickets here.]

In the early 1960s, films featuring surfing were either niche, all all-action affairs or cheesy mainstream blockbusters that felt wholly unrepresentative to real wave riders.

Then, in 1964 a film came along and changed all that. It bridged the gap between the landlocked masses and the surfing tribe, reshaping surfing in the global psyche and creating a blueprint for travel and film making that has endured ever since. The film was The Endless Summer.

In 1963, after a spate of moderately successful surf movies, Californian filmmaker Bruce Brown told his travel agent he wanted to fly to South Africa for his next project. After complex flight routes were examined, he was informed it would be $50 cheaper to circumnavigate the world, rather than flying in across the Atlantic and back out the same way. And so, the idea for a surf film chasing summer across the globe was born. “We worked out a schedule so that we would miss connecting flights and purposefully had to stop over,” he told the Guardian, many years later. “We were hoping to get the airline to pay for our accommodation that way, but they never did.”

Bruce took out a 50k loan against his home and invited two California surfers, each of whom had featured in his previous works, along to star in the film. Their only requirements being the ability to take several months out and pay their own airfares. They were; wholesome 18 year-old goofy foot Robert August, fresh out of high school, but happy to put college on hold and 21 year-old regular foot Mike Hynson, who having never travelled outside the US and Mexico before was keen to see the world and even keener to avoid the Vietnam draft.

Mike asked his employer, board-building pioneer Hobie Altor, if he could lend him the $1400 for his airfare. On paper his chances didn’t look good; Hobie had caught Mike stealing boards from his factory just a few years prior, but luckily he was a forgiving soul and agreed to stump up the cash. He also provided Mike with boards for the trip, including a prototype bi-sect model, which consisted of two halves held together by a bolt in the centre that could be unscrewed, so the board could be folded and stashed in an overhead plane locker. Unfortunately, the design caused the board to bend and flex unpredictably in big surf and so it never made it off US soil.

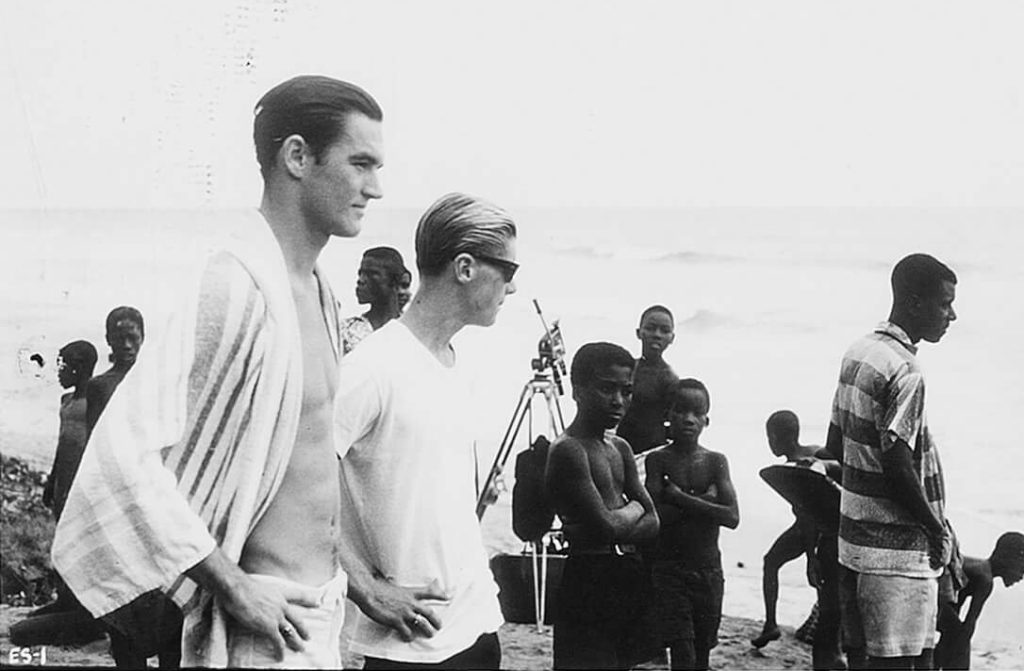

In November of ‘63, Robert, Mike and Bruce marched through LAX airport, dressed in suits, with 10 foot boards tucked under their arms and 20 pounds of camera gear, bound for Senegal.

The following day, they touched down in Dakar, where they beguiled locals with their surfing antics before heading onwards to Ghana and Nigeria. While some of the voice over gags that accompany this segment seem dated by today’s standards, the lighthearted delivery and the surfer’s jovial approach to the people and surroundings set the tone for the rest of the film and indeed, much of the global surf travel and filmmaking that followed in its wake.

It showed surfers how to glide through unknown lands and how to document their experiences, where cheery interaction with locals was encouraged, but any deeper engagement with the wider social or cultural issues unnecessary.

The film was, of course, a-political by design. Brown always intended for it to serve as an escape for an American audience beset on all sides by political upheaval. For an hour and a half, viewers would be invited to ignore the global roll call of war, assassination and segregation and instead ride along with a pair of young Californians interested only in fun and adventure, welcomed warmly wherever they went.

The trio had already been travelling for a few weeks by the time they arrived in Cape St Francis, on South Africa’s southerly tip, to shoot what would become the film’s most iconic sequence.

Their transport for the few days prior had been a cramped land cruiser, piloted by a big game hunter with a weird sense of humour named Terrence, and although still on the opening leg of the trip, the crew were already starting to get on each other’s nerves.

“I was smoking pot and taking bennies, so I would ramble on a bit,” remembers Mike in an interview with the Guardian. “Robert had diarrhoea for a couple of days,” he continues, of the evening they rolled into Cape St Francis, “so I was glad to escape from the back of the truck.”

The next morning Mike got up to check the surf at 5am, wandering off down the coast while his companions slept soundly in their beachfront hostel. At first, he found nothing. But, as the tide came in and he ventured further south into the crook of the bay he thought he spotted small breaking waves peeling down a point in the distance. “I wasn’t keen to paddle out by myself, with all the sharks, but I thought, fuck it,” he remembers. He grabbed his stuff and set off in the direction of the wave. When he got in front of it, he watched with awe as a three wave set spun perfectly down the point. Suddenly, he didn’t care that he was by himself. He jumped and paddled out, catching a wave almost immediately.

As he kicked out, he looked down the beach to see August and Brown running along the sand towards him, dragging all their gear behind them. August soon joined Mike in the lineup, reportedly arriving at the peak so overcome with excitement, that he vomited into the sea. For the next 45 minutes, the pair traded waves that would go down in history.

It wasn’t until the following day, when the waves went flat, that Brown filmed the boys walking over the dunes and pretending to discover the point, paying homage to surfing’s already time-honoured tradition of not letting the truth get in the way of a perfect surf story. (Which, incidentally, is one of the central themes of our latest print edition).

The sequence introduced the surfing world to the concept of ‘the perfect wave’ and the idea that chasing it is a valuable lifelong pursuit. It showed surfers exactly what to seek; long, empty peelers, breaking way off the beaten track and even how to ride them; with a soul arch and casual nose drain without ever breaking trim, establishing a plot and collection of tropes that would underscore surf filmmaking forevermore.

After South Africa, the group flew to India, with Mike strapping the film canisters featuring the mesmerising St Francis footage to his torso, over fears it may be confiscated in Mumbai airport. While much of the film was sent back to the US to be edited, Brown refused to let that reel out of his sight, keeping it on his person for the entirety of their remaining voyage.

From India, they headed to Australia and then New Zealand, where they reportedly promised terrified (and seemingly prophetic) locals they would not include the location of the Raglan footage in the final edit. Then Tahiti, for perhaps the earliest precursor to a JOB vlog, then Hawaii and then back to California, just in time for summer to begin there.

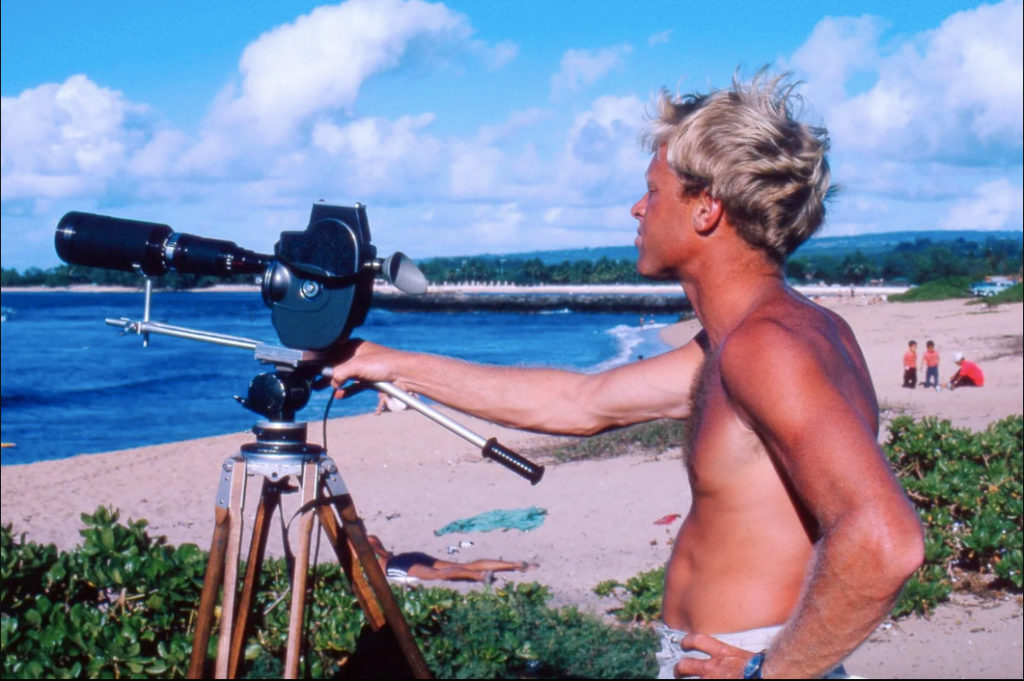

Once editing was complete, Brown began touring the film around clubhouses and school auditoriums. As there was no sound, he would stand on stage narrating the action and pressing play and pause on the music manually. He had the chance to workshop his now iconic commentary routine with around 100 different crowds, testing out different jokes and descriptions, before laying it down on the final voice over track. Despite a warm reception from audiences, studios remained disinterested in distributing the film nationally, with one reportedly telling the film’s promoter Paul Allen that it would never play more than ten feet from the beach.

They also didn’t like the poster (needed a girl in a bikini, apparently) and even when the film was finally picked up Bruce had to battle for it not to be changed.

In the decades since of course, the artwork has been praised as one of the most iconic of the era and according to Shepard Fairey, founder of Obey, and creator of the Obama “Hope” poster, may even be the “most pervasive surf image ever created.”

In an attempt to prove to the studios the film held appeal away from the coast, Allen booked out a cinema over a thousand miles away in Wichita, Kansas. The city is about as far away as you can get from the beach in the States, but somehow, he managed to sell out the entire two week run. From there, they took it to New York, where a series of rave reviews finally convinced a big-time distributor to come on board. Soon, the film was selling out cinema screenings across the world, going on to gross a whopping $20 mill.

56 years on and the boards, surfing styles and locations visited have changed almost beyond recognition, but the fantasy at the heart of the film burns as brightly as ever in modern surf culture.

[Join us for a special drive-in screening of the film in Watergate Bay, Cornwall on Saturday 15th August. Get your tickets here.]

Recent Comments