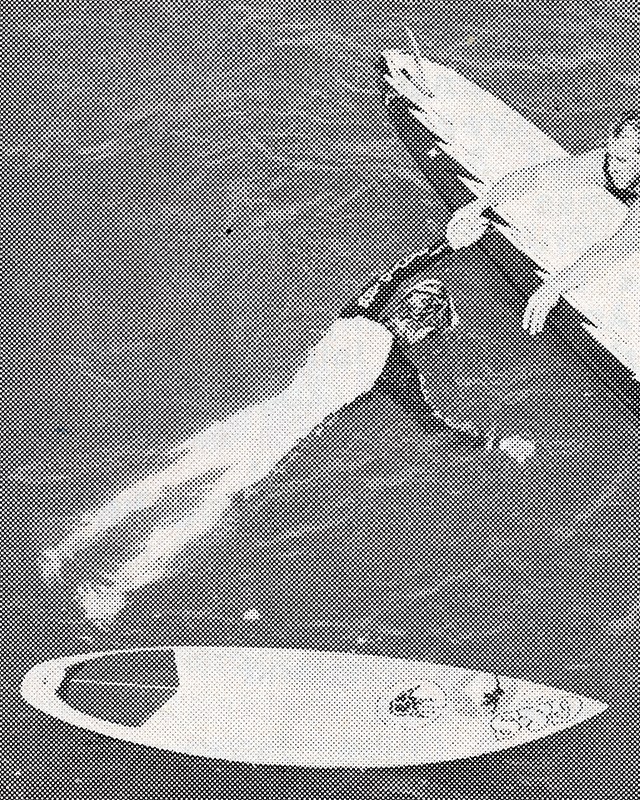

“Sex sells” is an adage that publishers and agency executives have embraced since time immemorial. And, historically speaking, perhaps no media space has committed to that line more than surfing. From John Peck’s classic “Penetrator” surfboard to Lightning Bolt ads featuring Rory Russell encircled by bikini-clad models to the faceless Reef girls hawking sandals, surf marketing and media have a long, not-so-subtle history of sexualizing our aquatic lifestyle. Hell, this magazine once just ran the word “SEX” in all caps as a cover blurb in the early ‘00s.

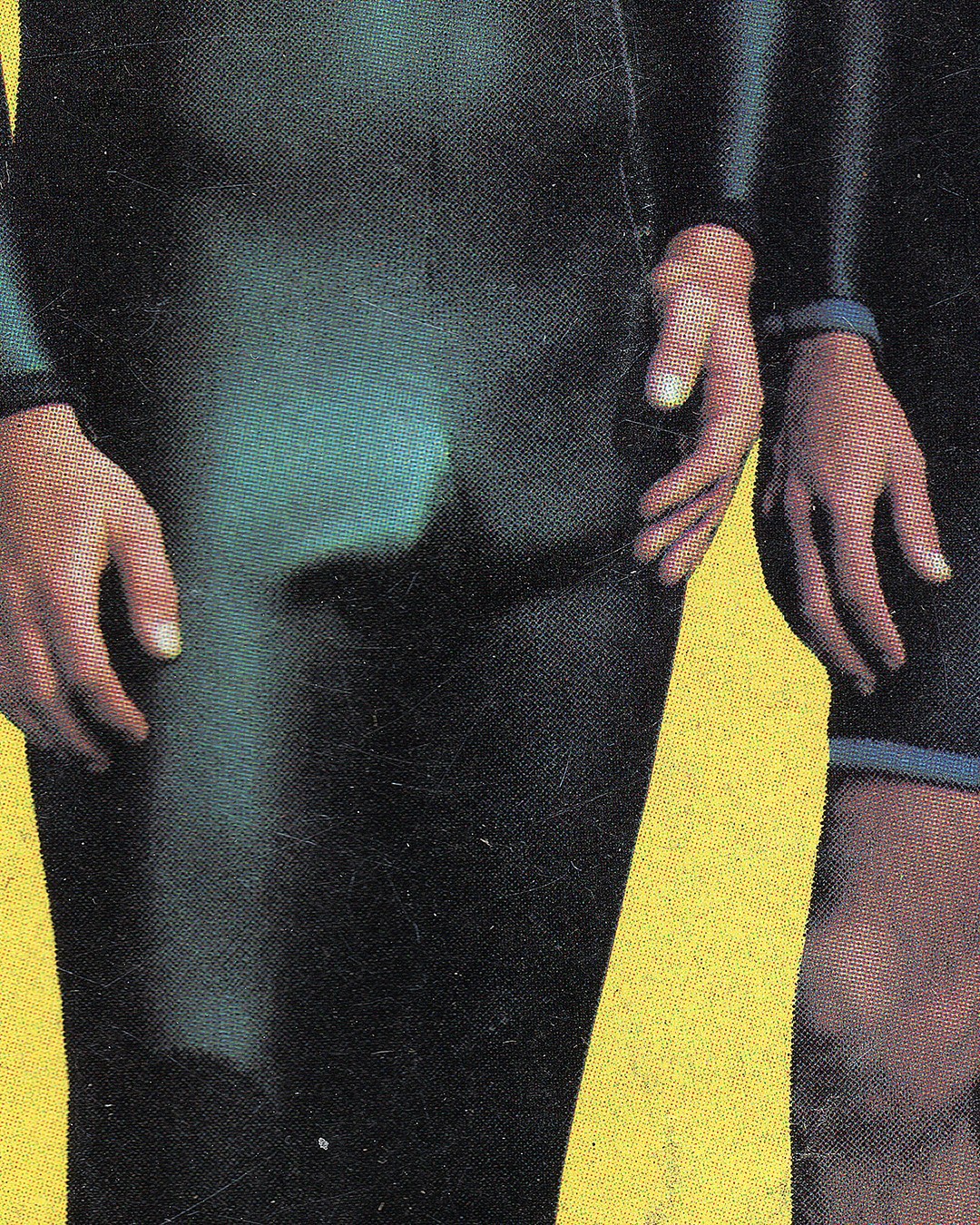

The iron-clad rule of that sexualization, especially in decades past, was that it must always embody a male, heteronormative perspective. The historic depiction of women in surf media? Seldom very clothed, often objectified, sometimes even when it came to some of the greatest female surfers of all time. Men? Also scantily clad, sure, but typically either ripping the bag out of waves or surrounded by beautiful, half-naked women in advertisements. “Yeah these guys hunt exotic waves around the world while perpetually in the company of other men, but they’re as straight as the day is long,” the ads seemed to insist, “and you can be, too, for the price of these boardshorts!”

While this imagery was surely alienating for most LGBTQ surfers (not to mention women), at least one saw a unique opportunity in the hyper-sexualized hetero-normativity of old surf mags. Enter Stephen Milner, a San Diego-based surfer and artist whose upcoming book, “A Spiritual Good Time”, appropriates old images from surf magazines and places them in an entirely new context – one that creates a vision of a far more queer-friendly surf culture.

“When it comes down to it, masculinity in surfing is extremely fragile — once you start poking at it, it just comes apart,” says Milner. “Looking at old surfing magazines, a lot of the images that I’m appropriating in this book or showing in my solo shows, I literally cut out women who were posing in bikinis underneath these men. It might be a wetsuit ad, so the bikini has nothing to do with the wetsuit — she’s just there to create sexual indulgence. When I started to cut out these sections, I started to feel that I had my own power to control the narrative in these mass-produced magazines.”

We recently gave Milner a call to learn more about the concept behind “A Spiritual Good Time” (which you can pre-order here), his process and why surfing culture is such fertile ground for queer art.

I think I read somewhere that you grew up in a small farming town. Can you kind of tell me about that and what your early surfing life was like?

I was born and raised in the North Fork of Long Island, New York. It’s historically a small farm town, and if you want to go to the ocean — which would be a family excursion, like a weekend thing in the summertime — would be like a 20-minute drive to Montauk, which is of course a big surf community. So yeah, I started surfing in that area when I was a teenager.

As a gay teenager in a small town, it was very hard growing up. I knew I was gay, but I still had a girlfriend and I was playing sports and stuff like that, just finding ways to come across as more masculine. I was drawn to surfing because I would see this community of male surfers just hanging out and surfing and it felt so free and open. There is this spiritual looseness about it that I was really excited about. It also just gave me something fun to do.

Surfing can be super tribal and hierarchical, not to mention the fact that in that era homophobic slurs were super common in lineups. As a gay man, did navigating that space feel somewhat dangerous?

Oh, yeah, definitely. It was kind of scary, but also exciting. I liked the masculine figures out there, playing this role of protecting the water and the land, and who were very aware of who is out there and who is surfing well, and of course I wanted to impress people and earn a place in that community. But yeah, there’d be a lot of locker room talk out there, and I always felt like I had to pretend to be a certain way, to make these false statements that suggested a heterosexual lifestyle. So I kept it secret the whole time I lived and surfed there. I didn’t come out until I was in college in Savannah, Georgia, and even then I never told my surfing and skimboarding friends there. I had a partner for 3 years and none of them knew. There was this fear of maybe getting kicked out of this community, or of people just not feeling comfortable around me anymore. I didn’t want to lose that camaraderie. So I didn’t fully come out until I moved to Oregon for grad school, where I started making work about my queer identity.

Speaking of which, can you tell me about the process behind the new book?

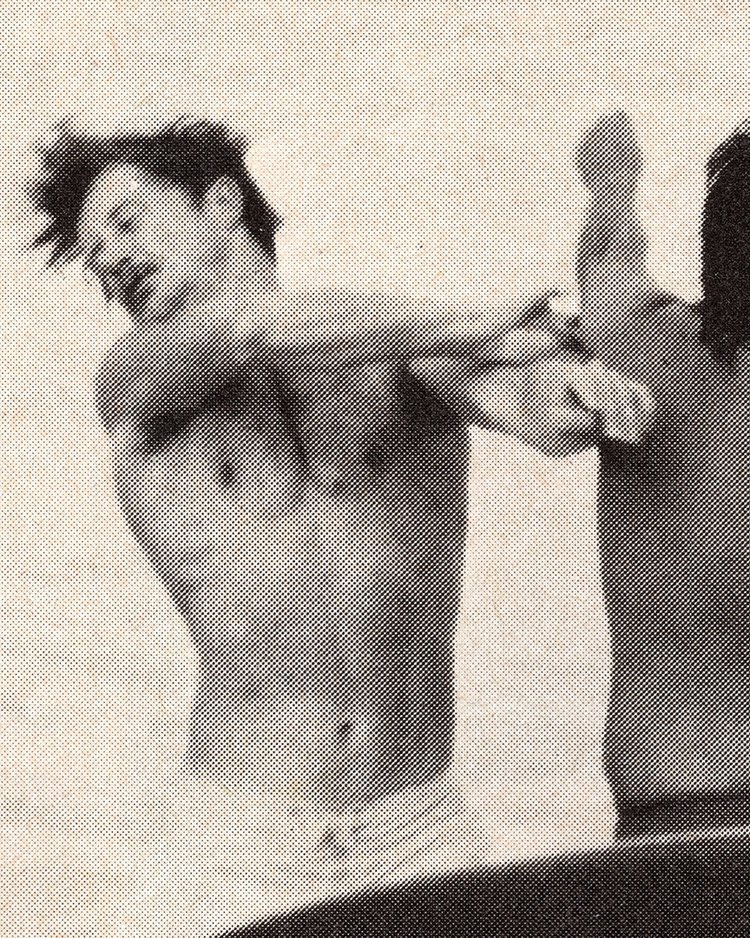

Yeah, definitely. So I have hundreds of vintage surf magazines that I constantly look through and read the articles and I look at the pictures, and for this project I’ve been playing this historian role, tracing it all back to the beginning. I’d cut out little sections of these images from the surf magazines that aren’t really the focal points – not the hero surfer getting barreled or carving the wave face. I would focus more on the camaraderie on the sidelines that wasn’t really important to the tropes of surfing photography. From there, I started to create this queer surf narrative that never actually happened, working within the guidelines of appropriation. “A Spiritual Good Time” is talking about this new narrative that I’ve created through the history of surf photography. It’s toggling between these interpretations of violence and camaraderie, and people read it in different ways. Some people will think of it as violent while others see it as romantic. That’s the power of photography and art, having that meaning switch back and forth.

And mixed in with the old surf mag imagery is imagery from old gay porn mags, right?

Yeah, so my goal there was to find these intimate moments that were a bit more sexual, but also not at the same time. A rule of mine was to never make the imagery too explicit, the intimate moments should be nuanced. A lot of vintage porn actually fetishizes surfers, so that’s where I was pulling those images from.

It’s funny because when I was like looking through some of the images from the book, it was hard to tell which ones were from surf mags and which were from porn. I wonder how well the average surfer would do at guessing which came from where.

It’s actually really funny, because when I first started this project, I had a lot of direct messages that were basically hate mail from surf photographers and older surfers in the area who found my work and didn’t get the context of appropriation. They’d be like, “You’re riding off other surf photographers backs. You’re a crook, you’re a cheater.” But I had one photographer who was just like, “I recognize some of these images.” I was like, “Alright, do me a favor and let me know which images you recognize.” I was curious if these photographs are historic enough that people may really recognize a cropped portion of someone’s hand or whatever. And so he picked one of the images and said, “I know this image. It’s from SURFER Magazine. I just can’t put my finger on which issue. I’ll find it though.” And I let him know that the image he picked was actually from a vintage porn mag. It turned into this conversation explaining contemporary art in the vein of Andy Warhol and Richard Prince and all these artists working with appropriation. If you see my work up close, you’ll notice that it’s not the original. You can see the evidence that it’s been mechanically reproduced. Eventually he was just like, “Whatever, man, I guess if you’re making good art, you have to ruffle feathers.” And then he blocked me on Instagram.

The compliment-to-block combo, I don’t think I’ve ever heard of that before. It’s interesting, though, since you really have multiple audiences at play, between surfers, the art community and the LGBTQ community. How have the reactions from the non-surf communities been?

The Fine Art community’s reaction has been amazing. So as a little background, I’m a multidisciplinary artist. I started off in photography and then started picking up other materials in grad school and did sculpture and installation and video work. Appropriation, especially with images, is really important to contemporary art right now. And there’s a handful of other artists who work in that genre, too, and are talking about historical concepts and comparing them to today. So people in that community have been really great and supportive. The gay community has been amazing to me, too. But the surf community is a wild card, that’s for sure.

As far as subject matter goes, do you feel like surf culture is a pretty deep well? Do you think there’s a lot more to say in that space and you’ll keep pursuing that through your work?

Absolutely. I could be doing this for a long time. There are also sculptures — installations at iconic Southern California surf breaks that I’ll be working on, too. Those will be a little bit more in your face. So that’s going to be interesting. I have a ton of other ideas, too. The hard part is finding the time to make art, since you’re also working other jobs to support yourself, and it’s also expensive to do. For now, I want to get this book out and start dabbling in some project that will be outside of surfing. But I think I’ll always come back to surfing, because it is my passion. And, yes, surfing is a deep well and I’ve only touched on Southern California so far.

As someone who surfed for a long time before coming out, is it important to you that your work normalizes LGBTQ conversations in surfing?

It’s hard being closeted in the first place, whether you’re a surfer or not. But within the sport of surfing, we all know how hard it is and how much pressure there is to live up to this masculine, heterosexual ideal. It might not seem like a lot of pressure from outsiders, but when you’re stuck in a self-doubt bubble, it is really hard. You can see that through documentaries like “Out in the Lineup” where closeted pro surfers [like Australia’s Matt Branson] felt like they had to leave the Tour before they could come out, for fear of losing all their sponsors and having this big fallout. It’s a real issue. But, of course, a lot of people don’t think it is because they’re outsiders and they’re not living it. I also think it’s important to recognize that my voice is very small in the much larger and diverse LGBTQ+ spectrum. Many more people are out there and have stories and art to share with the surfing community that are more important than mine.

[Click here to pre-order Stephen Milner’s “A Spiritual Good Time”]

Recent Comments