Dani Burt is a World Adaptive Surfing Champion, Doctor of Physical Therapy and fierce advocate for … [+] gender equality in adaptive surfing.

Ashleigh Yob

When Dani Burt woke up from a 45-day, medically induced coma following a motorcycle accident to learn her right leg had been amputated above the knee, she was destroyed; angry; defeated. At 19 years old, she had just arrived in San Diego after leaving a toxic family situation behind in New Jersey, where she was born and raised; the thrill of being on her own, her new life opened up before her, quickly turned to despair after her accident.

Of course, with the power of hindsight, Burt, now 35, understands that her life was really only just beginning. A World Adaptive Surfing Champion, Doctor of Physical Therapy and fierce advocate for gender equality in adaptive surfing—still very much a male-dominated sport—Burt is the picture of resilience. But she’s not afraid of exploring those dark feelings she had when she first awoke from her coma in 2004 and was placed on suicide watch; doing so allows her to be the best advocate she can be as she works with fellow amputees or severely injured patients. It only serves to paint a more accurate picture of Dani Burt, the complete person, who is more than just your inspirational story.

“One of the reasons I was on suicide watch coming out of that crash is because the preconceived notions society has about someone with a disability had completely infiltrated my life,” Burt says by phone in late August, shortly after being profiled in the book She Surf: The Rise of Female Surfing and featured in an episode of Red Bull TV’s Out of Frame.

“I thought it was this negative horrible thing that would ruin my life, and it’s not; it’s just something that’s completely made up by society. Now looking back on that, for me personally, the words disabled and disability, I have no problem with that. I own that. That’s part of me, that’s part of my identity.”

Of course, before she could arrive at this place of peace, before she could spring into action to advocate for disabled patients and female surfers, Burt had to grieve her injury and learn how to move in the world with her changed body. After five weeks in bed, she awoke with a brachial plexus injury in her left arm, which was paralyzed, with no sensation from the shoulder down. She had collapsed lungs, a ruptured spleen, and severe internal bleeding. She couldn’t sit up in bed; initially, she didn’t even know her leg was gone. She had a tracheostomy, so she couldn’t speak. That she couldn’t advocate for herself or consent to the amputation was a source of anger she had to work through early on.

But being young and otherwise healthy, it didn’t take long for Burt to bounce back. She could move her arm; then, her left leg with physical therapy. She could sit up in bed. Eventually, she did inpatient and outpatient occupational therapy and speech therapy. Burt had suffered a brain injury from coding twice and the subsequent lack of oxygen, and she and her physical therapists were working on her cognition.

It also became immediately obvious that she needed good health insurance as her bills skyrocketed above $2 million (before the accident, she was working at a San Diego Home Depot branch she had transferred to from New Jersey).

Burt’s therapists recommended she look into community college; Burt laughed. She had never planned on going to college. “But seeing what my physical therapists were doing for me to get my functional mobility back and become independent again, I thought, That must be the most rewarding, amazing job you could ever do. To do that for someone else is amazing. I’m down to go to community college as a physical therapy assistant.”

Burt was accepted and started her program a little more than six months after her accident, taking one class at a time. Adjustment doesn’t begin to describe the beginning. “I had the worst prosthetic leg; I couldn’t even walk a block without falling multiple times,” Burt chuckles. “I was getting used to how people treated me now that I was disabled—all eyes on you all the time reminding you of this horrible thing that happened—and being in a body that you don’t even really know how to work anymore and trying to figure that out.”

As she was working toward her physical therapy assistant certification and finding that everything was getting easier mentally and physically, a friend asked why she wasn’t going for physical therapy. Her response: “Because it’s a doctorate, and I didn’t want to go to college in the first place.” But after thinking about it, Burt realized she didn’t have a good enough excuse not to try. She transferred to San Diego State to complete her bachelor’s degree, and in one of many strokes of fate, karma, divine intervention—whatever you want to call it—Burt has experienced in her life, San Diego State also that year began offering a doctorate in physical therapy. She applied and was accepted.

A physical therapy doctoral program requires its candidates complete internships. For one of hers, Burt wanted to go back to Sharp Memorial Hospital, where she had been a patient, and wound up working as a student of the therapist who treated her. As Burt was nearing graduation, in another stroke of fate, Sharp had an opening for a physical therapist.

“Even before I walked for graduation I had a job with them,” Burt says. “It’s such an honor to work with some of the same therapists that were my therapists and to fully give back and pay forward everything that people have done for me.”

When she began college, Burt had yet to even take up surfing seriously. It’s fairly unheard of for an adaptive surfer to have not surfed prior to their injury, Burt says. She had board knowledge from growing up skateboarding and bodyboarding in New Jersey, but the ever-changing platform of the waves and the body control were difficult to master at first. Notwithstanding, Burt is grateful that she found surfing after her accident.

“It was so nice to do something that I didn’t do before I lost my leg,” Burt says. “Going back to skateboarding and bodyboarding was painful for me emotionally, even physically. I kept breaking things. As something still totally new and beautiful and fun, surfing definitely helped me get to where I am today.”

Living in San Diego, surfing, at first, was “just for funsies,” Burt says; something to do just for herself. “I just wanted to be in the water again,” she says. “I grew up in the water and it’s something I consider home; the ocean just does something to you emotionally and mentally. You don’t feel complete without it. It’s an amazing feeling.”

Burt entered her first competition in Hawaii in 2010 after someone “randomly ran up to her” on the beach and invited her to join an adaptive surfing competition. She came in third against all-male competitors.

When the International Surfing Association debuted the World Adaptive Surfing Championships in 2015, the organization reached out to Burt and explained they were organizing a competition that they one day hoped to get into the Paralympics. In 2016, she was named the U.S. Adaptive Surfing Champion competing in a mixed-gender division. In 2017, Burt competed in the first-ever adaptive surfing all women’s division and won.

As Burt met other surfers at the competitions, she quickly began to treasure this community in which she wasn’t an adaptive surfer; simply a surfer. “Meeting them in person and being at this event, it was extremely humanizing,” she recalls. “In my day-to-day life, I can’t go a day without someone asking me about my leg, but at something like this, it’s not a factor. I don’t know why most of them lost their leg; we’re humans, we love surfing, we’re gonna talk about surfing.”

This is how performing the role of being an inspirational story can become exhausting. Burt, like all adaptive athletes, is a fully formed person who has good days and bad days and everything in between. She appreciates people who compliment her surfing when they see her on the beach, but being a billboard for inspiration every waking moment can be draining.

“A lot of my friends sort of make fun of me because I always want to go surf at dawn,” Burt says. “They’re like, ‘That’s way too early.’ I just don’t want to be asked about one of the worst moments in my life. I want to do what I love and be at peace with it. I’m grateful for people who say I’m an inspiration, but a lot of the time they haven’t even seen me surf. Am I inspiring because I decided to wake up today? Just because I have one leg doesn’t mean my life is over.”

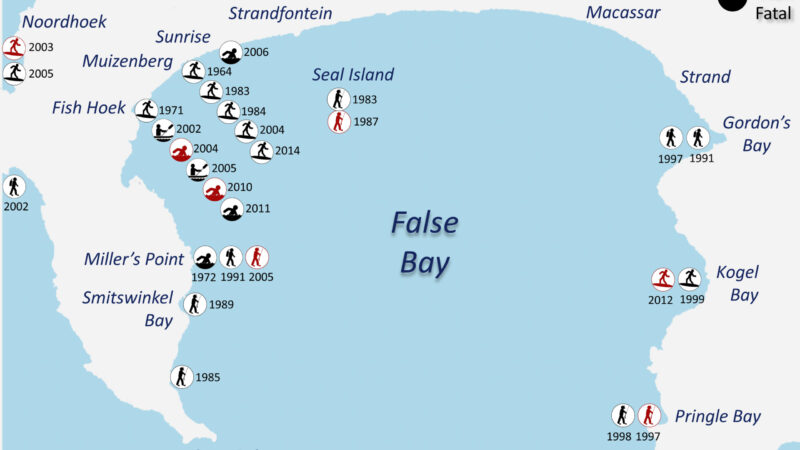

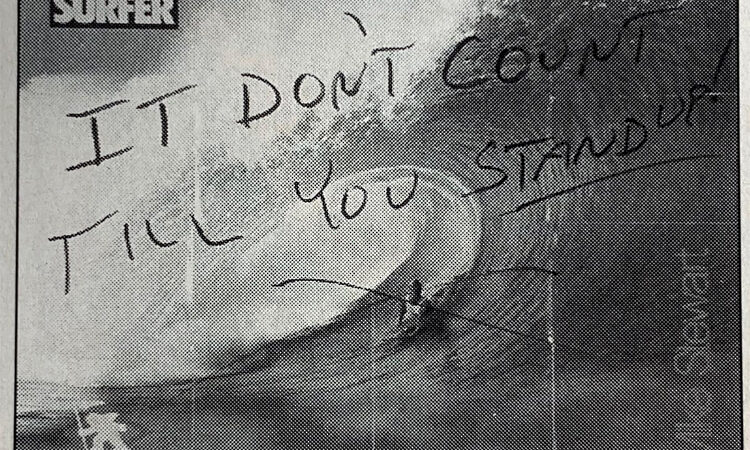

Coupled with being a female athlete in a male-driven sport, who are often exalted as role models before competitors, Burt can often feel like she’s fighting for recognition for what she wants to be seen as first and foremost: a surfer. Women make up between 20 to 30 percent of surfers, professional surfer Lauren Hill writes in the foreword to She Surf. Representation is still virtually nonexistent. When Burt would walk to her local library in New Jersey growing up, she would pore over the pages of Thrasher and Surfer, looking for anyone who looked like her. “Brown, woman, gay, anything—there was never anything to see,” she says. “You have this overwhelming feeling that you don’t belong.”

Gender representation is improving slowly in surfing, with more women in the lineup. But the contrast remains stark at ISA and World Surf League (WSL) competitions, which has spurred Burt to action. In ISA events, surfers are awarded points, but women’s scores did not count. For the 2018 Adaptive Surfing World Championship, the ISA attempted a compromise with women’s scores weighted at just 50 percent of men’s in the team competition. Burt and other female surfers were not satisfied with that.

“As far as competitions and the world championships, it’s relatively new for adaptive surfing,” Burt says. “For a new sport to be injecting gender discrimination, to me, that’s just crazy. I’m not down.” She penned a letter to the ISA protesting the decision, which was signed by 17 adaptive surfers, event organizers, and advocates around the world. Because surfing isn’t her main moneymaker, she was willing to risk putting her name out there. “I was willing to say something about it and potentially never win a world championship again,” she says.

The ACLU jumped onboard; California city council members jumped onboard; and on the same day the ISA responded about equal points, the WSL responded with equal prize money for women. As Burt points out, the ISA isn’t just the governing body for adaptive surfing; it also runs juniors, longboarding, shortboarding. “It’s across the board that they can’t do this again to women,” Burt says. “That was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done—but the most gratifying.”

Now, the ISA has its sights set on getting Para Surfing added to the Paralympics program. Surfing will provisionally debut at the Tokyo Olympics in 2021, with 20 men and 20 women competing in separate competitions on Japan’s Pacific shoreline. For Paris 2024, the surfing events will take place at Teahupo’o, Tahiti, in French Polynesia, which features some of the world’s most dangerous waves.

Para Surfing will not debut in the Paralympics in 2021 alongside surfing in the Olympics. The classifications weren’t where they needed to be, Burt explains. The goal is for Para Surfing make it into the Paralympics in 2024. “Even though competition isn’t my life, if given the opportunity I would definitely train for that. It would be an absolute honor,” Burt says. She describes the ways the Paralympics would advance not only adaptive surfing but the world, increasing visibility and acknowledging the issues with accessibility to the beach and to the oceans.

Whether it’s advocating for gender equality in surfing or for her patients as a physical therapist, at the core of everything Burt does is an acute awareness of her own experiences.

“I know what it feels like, whether it’s gender inequality or discrimination based off race or disability, in the surfing community or otherwise,” Burt says. “When someone else is feeling that I just want to be like, ‘You’re not alone.’ Overall I want to make it more visible and just represent and love and truly protect my friends and my community and people that are more marginalized.

“When I was hurting a lot in the beginning, that’s all I really wanted to hear,” Burt says. “I wanted to hear truth.”

Recent Comments