In the opening essay to The 1619 Project, a multimedia project commemorating the arrival of the first enslaved Africans on the shores of what became the United States, at Pointe Comfort, Virginia, Nikole Hannah Jones reflects on the function of the transatlantic slave trade on Africans forcibly transported to the Americas.

The teal eternity of the Atlantic Ocean had severed them so completely from what had once been their home that it was as if nothing had ever existed before, as if everything and everyone they cherished had simply vanished from the earth. They were no longer Mbundu or Akan or Fulani. These men and women from many different nations, all shackled together in the suffocating hull of the ship, they were one people now.

In reflection on 400 years since the advent of Black enslavement in the United States, we return to another commemoration at Virginia’s Atlantic coast, which focuses on that moment of attempted “severance” of African peoples from their names, their cultures, and their histories. The International Day of Remembrance, hosted by The Sankofa Projects of Hampton Roads, Virginia, is part of a multinational remembering of the Middle Passage. Rather than highlight the severing of ties to African homelands, Sankofa Projects founder Chadra Pittman views Remembrance as honoring the estimated 2 million who died during the Middle Passage through reconnecting to African cultural retentions, the things that were not severed, during slavery.

Here is Scalawag’s coverage of The Sankofa Projects’ Remembrance commemoration in 2016, originally published in May 2017.

In Dahomey (now Benin), the Dutch, the Portuguese, the British, and the French captured African women, men, and children from the interior of the country and marched them hundreds of miles to a coastal town called Ouidah (pronounced “why-dah”), to a tree the Europeans believed had magic powers of amnesia.

The Tree of Forgetfulness was not like the lynching tree of White American carnivals, serving tea in front of tortured Black bodies. But the latter lynchings depended on the former ritual. The Tree of Forgetfulness stole identities. The Europeans believed that if Africans walked around it—nine times for men, seven times for women and children—Africans could erase their own histories, lose themselves in space and time.

Once detached, they could be reinvented as they packed the dark hull of a westward bound ship. They would fight for little, because they remembered nothing.

I wonder how many of these lies were necessary for the Europeans to convince themselves that African humans did not exist; to reassure themselves of their own humanity.

Four issues each year for only $29.

Twelve and a half million Africans shipped forcibly to the so-called New World from 1525 to 1866 in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Ouidah was just one port of departure. At least two million died en route—by murder, suicide, illness, exhaustion, shipwreck—their bodies occupying the bottom of the Atlantic.

These are facts that I know like I know the geography of my last name, and that gravity is indifferent to the movement of ocean tides—no matter who they carry away.

Time doesn’t change them. But maybe time travel could.

Chadra Pittman Walke is an anthropologist living in the Hampton Roads area of Virginia—a place that time forgot, at least for a while. Most U.S. histories place the first enslaved Africans on the shores of Jamestown, Virginia in 1619; but as she told me, current research shows that the first landing actually occurred at Point Comfort, which is now the City of Hampton.

I first met Chadra—a friend of my girlfriend’s—at a restaurant in Hampton a few months after Staten Island police strangled Eric Garner during his arrest, disregarding his pleas that he couldn’t breathe. Around the same time, a 6’4” White cop in Ferguson compared 18-year-old Mike Brown to Hulk Hogan and said he “looked like a demon” before shooting him dead with at least six bullets.

Chadra wears her history—cowrie shells and feathers in her hair—an homage to her West African and indigenous heritage. Her accent is from the Bronx, New York. She spoke energetically about her passions—ending violence against women and femmes, preserving African cultural practices in the United States, and commemorating the Middle Passage of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade.

We talked about how Eric and Mike, like Rekia Boyd and Aiyana Stanley-Jones before them, could not survive the lies told about them and their families to reassure us all of the officers’ humanity—to validate their lack of accountability.

The country disregarded their lives because it needed to believe that Black folk were nothing more than the humanoid invention of American imagination. If we had no usable past, our futures didn’t matter.

In 1991, while Chadra was an anthropology student at George Mason University, construction workers excavating part of lower Manhattan for a Federal office building uncovered a 6.6-acre burial ground where the bodies of free and enslaved Africans were interred from the 1690s to 1794—one of the largest and most significant archaeological finds in U.S. history. Dr. Michael Blakey, a Black archeologist at Howard University, directed the excavation and research of 419 bodies from the site, now known as the African Burial Ground. Chadra jumped at the opportunity to move back to New York to work as a public educator at the Office of Public Education and Interpretation of the African Burial Ground Project.

Over 13 years, Blakey’s team traced the remains back to modern-day Congo, Ghana, and Benin, before their re-interment in October 2003.

Chadra still keeps photos from the site on her phone—she believes the spirits there saved her life, gave her a future. She left her job at the African Burial Ground after a dream in which they signaled repeatedly that she should leave. Two years later, the Office of Public Education and Interpretation, located at 6 World Trade Center, was destroyed in the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001.

In one of her photos is a mother buried with her child in her arms—wearing traditional Adinkra symbols and offerings. Chadra sees the community’s maintenance of these ancestral practices in the face of slavery as a means of resistance—a way to practice freedom, and lay a foundation for descendants to do the same, which they did.

“What was really striking to me was the way that the descendant community [in New York] came out and claimed these bones,” Chadra said. “We didn’t know who they were, we didn’t know who they were related to. Record keeping was horrible and especially of enslaved Africans. But the community came out and claimed the bones as their own.” Chadra explained, “They would pour libations, they would drum, they would dance.” She adds, “I was so moved by that.”

Chadra is convinced that the only way for Black people to change the future is through the past—time travel through memory. She invited me to join her and others at the Atlantic shore in Hampton. At the so-called beginning that wasn’t.

I’d never been comfortable with ritual and spirit work as a mode of resistance. My instincts lean towards political action, community organizing, legal fights. But after a while, I couldn’t keep track of the names of murdered Black people to shout at the protests. My Facebook timeline filled with videos of Black bodies threatened, beaten, shot. My dreams weren’t my own—I was dodging police bullets, fighting back, dying.

It took me two years, but I finally showed up.

Participants at the Day of Remembrance.

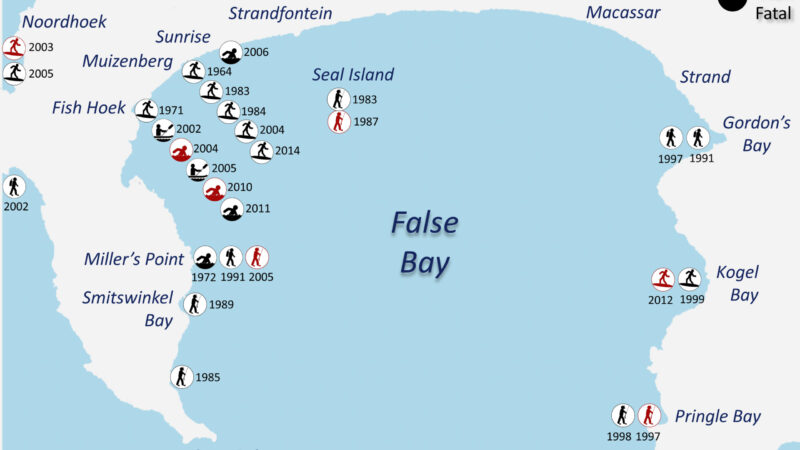

In Buckroe Beach, Virginia, on a cloudless day in June 2016, about 100 Black women, men, and children revisited that moment in Ouidah, at the Tree of Forgetfulness. Wherever our origins, our arrival on the shores of North America, of Central and South America, the West Indies, required a breaking away from our identities, however incomplete.

We circled a tree beside an old beach condo, men nine times, women and children seven, djembe players following behind. Orimolade Ogunjimi, a native of Newport News, Virginia and leader at Ile Nago, a cultural center devoted to African Traditional and African Diasporic Religions, called it the Tree of Remembrance.

“Symbolically, we let our ancestors know that we have not forgotten them, not forgotten our home, which is Africa. Not forgotten what our ancestors went through,” he said.

International Day of Remembrance happens every June on Buckroe Beach, a formerly Whites-Only resort that still appears that way. For five years, Chadra has reserved space on the beach for this ritual honoring the lives of millions of Africans lost in the Middle Passage during the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade.

“I always tell people, as [Jamaican Rastafarian poet] Mutubaraka said, ‘Slavery isn’t African history; it interrupted African history,’” she said. “And I kept thinking about the transport. What happened to the ones that perished along the way? And what happened to the ones who jumped in the ocean because they did not want to be enslaved? What happened to the ones who died before they got on the ships? They never got a proper burial.”

Following the tradition of Black author, filmmaker, and professor Toni Cade Bambara, who in 1989 began the Remembrance tradition in Brooklyn, New York, Chadra made International Day of Remembrance the first program of her organization, the Sankofa Projects.

“I named it Sankofa because… one of the coffins that we unearthed [at the African Burial Grounds] had metal tacks that were placed on top of the coffin in the shape of the Adinkra symbol Sankofa,” she said. “And the whole notion [the meaning of Sankofa], that we have to know where we’ve come from in order to know where we’re going, just really stayed with me. I didn’t want to focus on slavery as the genesis of our experience. Let’s go way back to who we were before they told us who we were.”

People arrived from across the country—from Cleveland, Ohio to Washington, D.C. to Mesa, Arizona—nearly 200 by the end, representing spiritual and religious traditions from Yoruba to Rastafarian to Christian. We mostly wore white, some head to toe, with geles, beaded jewelry and hammered brass. The early summer sun bounced from the water to our clothes, flooding our eyes with sharp white light.

The last light captured Africans saw in Ouidah was on the two-mile walk to the shipping port, having spent weeks or months in the darkness of European fortresses. In 1995, the former Beninese president Nicéphore Soglo inaugurated a monument at the port called La Porte Du Non Retour—The Door of No Return. Other “Doors” emerged on the coasts of Ghana (Elmina Castle) and Senegal (Gorée Island).

The Remembrance ceremony began with a drum circle, an invocation honoring elders and indigenous peoples, the “cultural retentions of the past” that Chadra says survived erasure by slavery.

“I have to ask the blessing of the elders to speak because they walked this land before I did, and I have to burn the sage because I want to cleanse the space of any negativity because we don’t know who’s coming,” Chadra said. “The Native component is important because I believe we have to go all the way back. So if we’re going to talk about the exploitation of African people, African bodies, we cannot do that without first…honoring Native spirits that were here and the Native blood that was spilled on this soil. [I want people] to see the connection across the spectrum.”

Twelve years before the first enslaved Africans arrived at Point Comfort, English colonists disembarked there to find the Kecoughtan tribe living and cultivating land along the river near the current site of Hampton University. The Kecoughtan survived English attacks for two years, until the start of the Anglo-Powhatan Wars in 1609 forced them to flee the land.

Over 250 years later, Union soldiers held Fort Monroe at Point Comfort during the Civil War, declaring that all slaves who could escape to Fort Monroe would be freed as contraband of war. The refugee Black community that formed there held their first classes around an old oak tree—now called Emancipation Oak. They built the school that became Hampton University in 1863.

Chadra decided to host Remembrance at Buckroe Beach, five miles from Fort Monroe, after learning the site offered a significant, time-worn history that she wanted to keep alive.

In 1898, three Black businessmen, some of whom were administrators at Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) built Bay Shore Hotel on eight acres of Buckroe Beach, which was then Whites-Only. For over 30 years, Black vacationers flocked to the resort, and it became a prime venue for Black entertainers, like Cab Calloway and Ella Fitzgerald. At its peak in 1930, it rivaled the all-White Buckroe Hotel and Resort, separated by 300 yards and a fence that stretched to the ocean.

Though Bay Shore was mostly destroyed by a hurricane in 1933, Chadra is committed to using Remembrance to recreate the spirit of that space of Black safety, community-building, and joy.

“[These] African-American businessmen in response to Jim Crow said, ‘We are going to create our own space. We are going to create a place for African Americans to come and to be at the beach and to spend time with their families and to enjoy each other and to laugh and to be free and to express themselves.’ I was so moved,” she said.

Remembrance at Buckroe Beach in 2016 looked like our images had been superimposed on a Whites-Only beach from the 1950s. We were sandwiched between dozens of White families—tanning, swimming, bodyboarding. There were barriers in the sand and buoys in the water separating us from them. They didn’t seem to notice us, with our drums and cheers and singing.

We formed a circle in the sand around Ogunjimi and Chadra, drums guiding the transition, umbrellas raised to block the unforgiving sun. He explained his ritual of libation—a covenant between the living and the spirit world, honoring the Yoruba gods of West Africa—particularly Nigeria, Togo, and Benin.

Chadra’s libation honored the Black lives lost across space and time.

They both poured water from wooden bowls. Chadra dropped red petals into the sand, symbolizing blood shed on these and other shores.

We spoke names we knew and referenced people whose names were lost to us—far beyond the Middle Passage. The re-calling recalled stories as well as names—Sandra Bland found hanging in a jail cell after a traffic stop, “Goddess” Diamond beat to death and torched in her car in New Orleans.

I thought about the patterns in the stories, how they were familiar by now, how they already shaped how we thought about the future, how we knew these stories would happen again because nothing had yet intervened to stop them.

I thought the scope of our memory in Remembrance had to extend far beyond the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, even far beyond the past. Our memory had to be non-linear—stretching forward, looping backward, repeating. We had to remember things not yet in memory—both horrific and joyous.

Nine months after the ceremony, this is more clear than ever.

The libations were for Denmark Vesey, a freeman who was executed in July, 1822 for planning a slave rebellion in Charleston, South Carolina with the aid of the Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

They were also for the nine Black church members who were massacred at Mother Emanuel in June 2015. And for Walter Scott, a Black man from Charleston who in May 2015 was shot five times by a White cop while running away from what should have been a routine traffic stop.

And, we also poured libations in memory of the 49 Black and brown queers, femmes, gays, lesbians, and trans-persons we didn’t know would be killed that same night in an Orlando nightclub by someone appearing to seek salvation from his own desire through their destruction.

And for Philando Castile and Alton Sterling, Black fathers who we didn’t know would be killed by police in St. Paul, Minnesota and Baton Rouge, Louisiana in the same week in July. And Deeniquia Dodds and Korryn Gaines—a Black trans woman and a Black cis mother—murdered in July and August.

“Somehow people want people of African descent to get over it. How can we get over it if it never ended?” Chadra said. “We can’t move beyond it. We haven’t reconciled. And it’s serving none of us to act like it didn’t happen. We can’t heal the wound without first addressing the wound. People wanna skip all that, wanna sing ‘Kumbaya’, but we are not okay.”

At the same time, as Chadra made clear, no one could address the wound without knowing joy.

A poet named Glo Shines paced the sand in the middle of the circle, grinning her way through an ode to melanin. We sang “Lift Every Voice and Sing” to the beat of djembe and talking drums. We danced and we laughed. Isheeba Karunza, a mental health specialist focused on gender and domestic violence, reminded us that community is still the best weapon against our own destruction.

And then we stood up, facing the ocean.

The Door of No Return is a slight misnomer. In 1835, Muslim Africans originating from Benin and Senegambia led a slave revolt in Bahia, Brazil, with hopes of overthrowing local government, freeing all the slaves, and commandeering a ship back to West Africa. The Portuguese crushed the rebellion, slaughtered the leaders, and kept their government intact.

Fear of future revolts, however, led them to organize a mass deportation of slaves back to West Africa.

The water was no more than chest deep where we entered against the tide, offerings in hand. We released flowers, oranges, spices, prayers. A family released the ashes of a loved one. I let myself float away with the flowers.

I thought about the 419 buried in lower Manhattan, the millions buried miles beneath me—how they found a way to leave behind the things that were supposed to disappear before they boarded the ship.

I thought about how everything that could happen had a usable past.

The tide got higher and so did the shrieks of the kids wading beside me. We turned our backs to the ocean and let the waves carry us to shore.

The 6th Annual International Day of Remembrance is sponsored by the City of Hampton History Museum and the Department of Parks and Recreation. It will be held on June 10, 2017, 11am at Buckroe Beach, Virginia. For more information visit http://thesankofaprojects.blogspot.com/

Recent Comments