I wasn’t born on the Texas coast, but as the old saying goes, I got there as fast as I could. I come from Temple originally, landlocked deep in the state’s interior. We didn’t lack for watery recreation in Central Texas, where there are plentiful creeks, rivers, and lakes, all of which we regularly availed ourselves of. But there was, of course, neither a sandy beach nor a Gulf of Mexico in sight.

That seashoreless existence came to an end when I was about four years old. In 1970, my dad, a hardworking Temple attorney active in civic affairs who had earned an occasional respite, purchased a small beachside unit in North Padre Island’s brand-new Gulfstream Condominiums. As the location’s name suggests, it sits at the northern end of Padre Island, which, at 113 miles from tip to tip, is the longest barrier island in the world. Back then, North Padre was a sleepy little seaside spot that didn’t qualify as a proper town. Even today it has escaped large-scale commercial development and seems happy to be overshadowed by the more famous—and more raucous—South Padre Island, which is favored by college students on spring break. For me, North Padre was a place of perpetual swimsuits, bare feet, and days on end with not a care in the world.

Throughout my childhood, we visited the condo often, and my mom and my two older brothers and I spent most of our summers there, with my dad coming down for weekends and, when he could get away from his law practice, for more extended stays.

Many of my most vivid memories are set on Padre: Beachcombing with my mom, who loved the coast more than any of us. Roasting marshmallows at the bonfires that my dad hosted for friends and any passersby who’d fall prey to his promise of hot dogs and the singing of songs of World Wars I and II. Fishing for sharks and redfish and speckled trout. Playing in the dunes and swimming. Experiencing my first real kiss, which happened on a warm late-summer evening somewhere around the seventh or eighth grade. She was a pretty girl, I think from Seguin. I also remember surfing and skateboarding and skimboarding and, later, experimenting with beer and Boone’s Farm and the like.

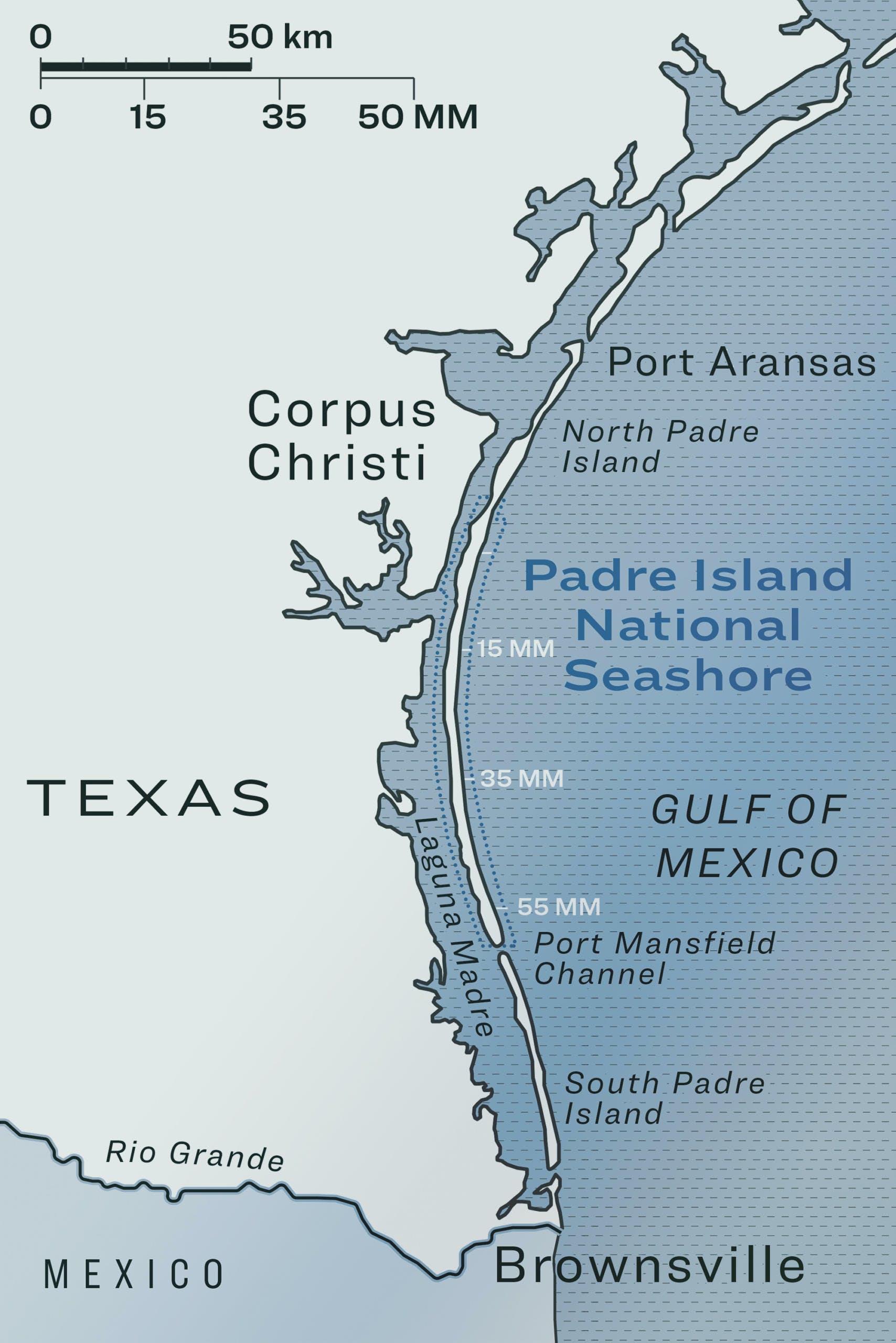

Map by Elsa Jenna

There are less idyllic memories, too. I recall the oily globs that inundated the beach after the Ixtoc I well blew out fifty miles off the Gulf coast of Mexico in the summer of 1979 and quickly spread massive quantities of oil to U.S. waters. Somewhere, I still have a small mustard jar containing a sample of the gooey sludge that I collected that year. I also have vivid memories of impaling my foot on the nail-like spine of a dead gafftop catfish that had washed ashore. A doctor friend of my parents’ dislodged the fish, which was stuck in whole, and applied enough pressure to my appendage that a stream of blood spurted out in a three-foot-long arc. And I remember Hurricane Allen, a category 5 beast that struck in 1980, destroying the old wooden Bob Hall Pier, a favored fishing spot, and wrecking large sections of the immense concrete seawall that runs along the beach in front of the Gulfstream. But despite such episodes, what I remember most are a lot of very good times.

My affection for Padre Island notwithstanding, it doesn’t get a lot of love from the rest of the world. None of Texas’s seashores do. They never make those lists of the World’s Greatest Beaches—not the 10 Best, not the 25 Best, not even the 100 Best. And that’s okay. Really, the omissions are not unwarranted. After all, there are no picturesque cliffs to offer vertical contrast to the relative flatness of the terrain. The water is as often as not a dingy brown color, the surfing is hardly world-class, and there’s almost always an overabundance of trash strewn about. Plus, thanks to the Texas Open Beaches Act, large numbers of vehicles often congest the shoreline. It’s not an image the design directors of glossy travel magazines think of when it’s time to choose a cover. Nevertheless, I love it.

One reason is the people I’ve met there. Throughout my early years, I made lasting friendships with other part-time residents: kids who hailed from Corpus Christi and farther-flung places like Laredo, Houston, Dallas, Chicago, and Mexico City. We’ve attended each others’ graduations and weddings and celebrated the births of each others’ children. My North Padre friends came to the funerals of my mother and my father and my brother. And, unfortunately, I’ve attended a few for their parents. These relationships have continued with the next generation. My daughter, Sarah, who is seventeen years old, is friends with the children of the children I met so long ago. Counting my parents and my friends’ parents, that’s three generations of island amity.

But I’ve got great friends in Austin, too, and Temple, and other places of varying degrees of flungness. North Padre’s unique attraction for me is the island itself, despite what all those snooty list-makers think. The sand, though often littered, is fine and white, and the water, though often murky, is sometimes clear and green. Either way, it’s almost always inviting and almost always full of fish. And the seashells are usually plentiful. Our condo, a cozy little space, is filled with the bounty of the many beachcombing walks that my family has taken over the course of five decades.

Recently, to commemorate the fifty years I’ve spent enjoying sandy adventures on the coast, I decided to do something befitting the occasion. I decided to take a long walk on the beach. A very long walk. I decided to do something I’ve never done before, something I’m not sure anyone has ever done before: beachcomb the entire length of the Padre Island National Seashore. All 65 miles it.

For the unfamiliar, PINS (“Pinz”), as the locals refer to it, is a national park made up of the 203-square-mile middle section of Padre Island, stretching from about 10 miles south of Packery Channel, which connects the Gulf to the Laguna Madre and Corpus Christi Bay, all the way down to the Port Mansfield Channel, which connects the Gulf to the Laguna Madre at tiny Port Mansfield. The expanse of national seashore that I planned to walk is the longest stretch of undeveloped barrier island in the world. Save for the visitors center and a few semi-primitive campsites near the park’s entrance at its north end, it’s totally wild. There’s nothing—no bathrooms, no showers, no water stations.

Looking west, toward the Laguna Madre, from the top of a dune around mile marker 55.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

A walk of this sort would, I figured, probably take somewhere between three and five days, depending on weather conditions and beach conditions, which can vary greatly and change rapidly. Soft sand, high winds, or high tides would make for hard trekking. Soft sand, high winds, and high tides would make for miserable, even impossible trekking. I was looking at April as a good time to make the trip, after the spring break crowds had dispersed, but before it got too hot, and well before hurricane season, which runs from June through November. I began planning accordingly, thinking about logistics, making a packing list, and keeping an eye on the weather forecasts, beach conditions, and tide charts.

What I failed to consider was that a global pandemic would bring almost everything to a grinding halt. On March 17, as the world was beginning to shut down, PINS announced that the park would remain open but that the visitors center would be closing. The nearby restrooms would stay open too, but all interpretive programming would be canceled until further notice. Then Governor Greg Abbott announced his first COVID-19–related executive orders. There were four of them, and they marked the beginning of the shutdown in Texas. I knew it might not be long before the park closed entirely, so I thought it wise to expedite things, and moved my trip up to late March.

I had decided early on that the best approach to a marathon beachcomb like this was to be as physically unburdened as possible. Carrying a pack full of gear and a three-to-five-day supply of water and food wouldn’t have felt right for the leisurely, albeit lengthy, stroll I was envisioning. And, honestly, it may have been more than my 53-year-old, not-super-athletic body was up to. So I asked photographer Kenny Braun if he and his assistant, Paul Andries, could come along and act as both documentarians and support crew. The idea was that I’d walk the length of the beach and they’d drive it, carrying all of our gear, food, water, and beer in two vehicles, one of which was my trusty old midsize four-wheel-drive Toyota SUV. We would rendezvous every ten miles or so—at lunchtime and then again around dinnertime, at which point we’d make camp for the evening. In between, Kenny and Paul were free to scout good spots for overnighting and to swim, surf, fish, play bocce ball, or whatever. Kenny, a noted surf photographer, thought this sounded like a pretty good deal.

And so, in late March we set off for an epic coastal excursion that would allow me to spend my days immersed in the fine art of beachcombing and my nights beneath a starry South Texas sky. While the rest of the world was hunkering down in isolation, I was going to partake in some social distancing of a different sort.

The beachcomber.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

Day 1

March 23

North end of park – MM 15

Shortly after ten in the morning, Kenny and Paul dropped me off on the beach at the line of bollards that mark the park’s northern boundary, and then made their way back to the main road, the paved Park Road 22. Shouldering a small knapsack containing water, a few snacks, a small towel, and sunscreen, I headed south. The conditions couldn’t have been better. The temperature was a mild 70-something with a forecast calling for a high of 82. There was a pleasant onshore breeze blowing maybe twenty miles per hour and the skies were slightly overcast with a hint of fog. To my left, the Gulf water was extraordinarily green, and the two-to-three-foot breakers produced a beautifully contrasting white seafoam. The beach sand was packed and firm and the tides were favorable. Seagulls cawed and long squadrons of brown pelicans wheeled silently overhead. The sun would set at 7:42.

PINS contains five rather unimaginatively named beaches. At the northernmost end there’s a short stretch known as North Beach, which is followed by Closed Beach (so named because it is closed to automobile traffic), and then South Beach, which runs down to the Port Mansfield Channel and contains both Little Shell Beach and Big Shell Beach. From the north end of South Beach down to the channel, mile markers are placed every five miles.

During that first mile along North Beach, I was struck with a great sense of relief. I took in deep breaths of fresh, briny air, and my worries about the fate of the rest of the world melted away beneath the emerging sun. Then, as I made my way down Closed Beach, a sense of solitude began to set in, allowing me to acclimate to my new environs and begin the necessary work of getting my footing, both physical and mental.

I didn’t see a soul the first hour, but shortly afterward I came upon a small crew of park rangers gathered around something of interest. I approached and a friendly ranger explained that volunteers were being trained to locate and collect turtle eggs. PINS is the most important nesting ground in the country for Kemp’s ridley sea turtles, the world’s most endangered species of sea turtle, and is home to the Division of Sea Turtle Science and Recovery, the only organization of its kind in the U.S. National Park system. In a matter of days, the ranger explained, the beleaguered turtles, one of five species found in the Gulf of Mexico, would begin to emerge from the sea and make their way up into the dunes to lay eggs.

The ranger bent down and made a series of little check marks in the sand, to show me what the sea turtles’ tracks look like. Every year, from April through July, rangers and volunteers work diligently to spy such tracks, which lead to the nests, from which they will collect the eggs and then care for them as they hatch throughout the summertime. As the silver-dollar-size hatchlings emerge from their shells, park staffers release them in large batches onto the beach, where they instinctually inch their way to the sea. The male turtles will likely never leave the water again, but the females, after roaming thousands of miles, will somehow manage to return, in a dozen or so years, to the same beach where they were born, to lay their own eggs. It’s an astonishing process, and I’ve taken Sarah to see a few of the releases over the years. They are something to behold, especially for a father accompanying his own young hatchling.

Photo assistant Paul Andries and the author rest near mile marker 5 on March 23, 2020.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

Sand dollars on the shore.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

Photo assistant Paul Andries and the author rest near mile marker 5 on March 23, 2020.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

Right:

Sand dollars on the shore.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

I thanked the ranger, wished her good luck, and continued walking, past the Malaquite Campground and the closed visitors center, and then entered South Beach, where I encountered a few RVers, some tent campers, and a smattering of day-trippers. There were also the occasional surf fishers, many of whom, I surmised from their out-of-state license plates, were winter Texans who had not yet begun their spring migration back to their Midwest summering grounds. I noted a Michigander couple’s “Toes in the Surf, Ass in the Sand” license plate frame. They had just reeled in a nice redfish—21 inches, just into keeper territory, they told me excitedly.

Before I knew it, it was two o’clock and I had reached mile marker 5, which actually marked 10 miles of walking for me, since the markers don’t start until you hit the drivable portion of the park at South Beach. Kenny and Paul were there, relaxing in the shade of a canopy. We had a lunch of oranges, trail mix, and grilled sausages and cheese wrapped in tortillas. I grabbed a cold Modelo and kicked off my shoes to wade in the cool water, which felt good on my already-tired feet. We assessed my progress thus far and noted the light crowd for such a beautiful day, which we figured probably owed to the coronavirus, coupled with the fact that it was a Monday. I soon refilled my water bottle, laced my shoes back up, said goodbye to Kenny and Paul, and started walking again.

The beach was not only light on visitors, it was also unusually light on trash. Texas beaches are almost always littered with all manner of natural and human-made debris. The fault for this lies not solely with our residents—who by and large know better than to “mess with Texas”—but with the interplay of coastal geography and ocean currents; our coast, and particularly this bending portion of it, is positioned where two opposing wind-driven sea currents meet, pushing marine debris from all over the Gulf—and beyond—onto the beaches in a constant deluge.

This particular stretch was likely so clean because the annual Billy Sandifer Big Shell Beach Cleanup, the twenty-fifth such event organized by the nonprofit Friends of Padre, had taken place less than a month earlier. Some 1,500 volunteers had spread out over 33 miles of beach and, in a single day, hauled out sixty tons of trash in four industrial-sized dumpsters. It’s a Sisyphean task—the trash will accumulate once again and there’ll be another sixty or so tons to pick up next year—but even weeks later the salutary effects of their hard work were still apparent.

More than ten miles into the trip, I had seen sundry bits of human detritus, a deceased puffer fish, and fragments of shells. But I’d come across nothing worth picking up.

The same natural influences that dump all this debris onto the beaches have a more beneficent result, too—they bring to shore seashells and other naturally occurring objects, such as driftwood and seaweed, which is good for the health of the beach, preventing erosion and providing sustenance for wildlife, although it sometimes arrives in quantities too large and malodorous to be fully appreciated. PINS is known for excellent shelling—I collected hundreds of shells from these shores as a child—and I expected to find no shortage of good specimens on this trip. But with more than ten miles in the proverbial rearview mirror, I was empty-handed. I had seen sundry bits of human detritus, such as a soccer ball at which, in an ode to the movie Cast Away, I yelled “Wilson!” I had also seen a deceased puffer fish, and some fragments of shells and sand dollars. But, to my surprise, I’d come across nothing worth picking up.

I was approaching Little Shell Beach, though, and I thought that surely a beach so named would be awash with shells, even if they were little ones. I looked forward to angel wings, Atlantic bay scallops, disc dosinias, common arks, Florida spiny jewel boxes, coquinas, giant Atlantic cockles, lettered olives, sand dollars, saw-toothed pen shells, and Scotch bonnets. And, of course, the prized lightning whelk, the official shell of Texas, which is, at least in my experience, quite elusive. The lightning whelk’s scientific name is Busycon perversum pulleyi. “Busycon” comes from the Greek word for “large fig” and roughly describes the shell’s overall shape; “perversum” comes from the Latin word for “turned the wrong way” and refers to the lightning whelk’s unusual left-sided opening, which makes it easily identifiable; and “pulleyi” honors the late Texas teacher, naturalist, and malacologist Dr. T. E. Pulley. The “lightning” in the shell’s common name is an ode to the distinctive stripes that run along its sides. My hopes were high.

But those hopes were thoroughly dashed. On Little Shell Beach I came upon little more than scattered refuse: a work shoe covered in moss, a clutch of Mylar party balloons in varying states of deflation, dozens of what appeared to be Golden Delicious apples, a fifty-pound bag of jasmine rice from Thailand, a large bundle of what looked like heavy-duty cargo netting, some Portuguese man-of-wars, an enormous moon jelly, a metal cooler much bigger than a standard refrigerator, and way too many of what I’ve always called “sea onions” but may actually be bits of invasive water hyacinth washed down from the many rivers that empty into the Gulf. From a distance these little devils can look a lot like lightning whelks, which led me to eventually change their unofficial name to “false whelks.”

By the time I reached mile marker 15, I had in my possession one unimpressive common ark and one nice angel wing. It was a disappointing haul for as much beach as I had combed, but there was always tomorrow, which would bring with it another twenty miles of opportunity.

It was about seven o’clock when I reached Kenny and Paul, who had pulled the vehicles up to the dunes and unpacked the coolers, set up a canopy and a tent, unfolded some chairs, and collected firewood. I felt good. My legs were, as expected, tired and my dogs were, as expected, barking, but overall I had, to my pleasant surprise, held up pretty well.

A coyote approaches the campsite around mile marker 15.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

Soon after I settled in we were joined by a curious and very bold coyote, who sauntered all around our campsite, trotting back and forth between us and the water, and even went so far as to dig at one of Paul’s bocce balls just twenty or so yards away. As the sky began to pinken, the three of us, sans coyote, climbed a large dune to watch the sun set over the Laguna Madre and the flat coastal plain beyond. The portion of the island behind the sandy foredunes, which stretches no more than a couple of miles at the park’s widest point, is covered in fields of brownish-green grassy dunes and sprinkled with yellowish mudflats. The glimmering Laguna Madre is visible off in the distance and there are no man-made objects in sight. The moist, light-diffusing Gulf air, coupled with the wispy clouds, turned the whole sky brilliant shades of orange, pink, and blue. It was gorgeous.

For dinner we had grilled chicken tacos with sautéed veggies. And Oreos. Then we retired to the campfire, where we talked about the day and how lucky we were to have made it to the coast. There was a new moon that night, and the dark and mostly clear skies, coupled with our remote location, made for excellent stargazing. A hint of city light from Corpus Christi to the north was evident, but even so, the stars were spectacular. I used to believe that nothing could beat a full moon rising over the Gulf of Mexico, so big and bright that as teenagers we’d sometimes swim in its glow. But beneath this evening’s moonless South Texas sky, the astronomical show we witnessed rivaled even the famous ones of far West Texas.

Just a couple of vehicles passed us in either direction, mostly fishermen coming and going. It had been as good of an evening as it had been a day, but after a few freshly mixed palomas and a few beers it was time to turn in. I crawled into the back of my SUV where, because of the steady, gusting winds, I had decided to bed down, instead of in the tent I’d brought. The back gate of the vehicle was open toward the ocean and as I lay there, I felt a touch of trepidation. The first day had gone well, but there were forty-five more miles yet to go. I had never in my 53 years attempted anything like this and wasn’t sure how I’d feel after another twenty miles and another twenty-five miles after that. Was I up to it? I wasn’t sure. But as the weariness settled in I mostly felt happy to be where I was, and the susurration of the wind and crashing waves soon sent me off to sleep.

Day 2

March 24

MM 15 – MM 35

As I awoke at daybreak, the winds had calmed but the sound of the surf was still crashing pleasantly against my ear. It was a few minutes before the sun would rise above the watery horizon and the partly cloudy sky was a vivid blend of pink and light blue. I sat up in my sleeping bag, taking it in. Just then, I noticed some movement out of the corner of my eye. Our coyote friend, an early riser, was already up and about. Even more bold than he had been the evening before, he—having grown up on too many Road Runner cartoons, I think of all coyotes as he—was right there in our camp, just outside my vehicle, sniffing around for spilled taco fillings and Oreo bits, no doubt. He moved on when he noticed me noticing him and I didn’t see the wily critter again.

Once up, I had some of Paul’s strong pour-over coffee and took a dip in the butt-clenchingly chilly water, which was so clear that as the waves swelled just before breaking, the early sunlight rendered them the color of old Coke bottle glass, translucent with a green hue.

After a breakfast of fruit, protein bars, and dried sausage, I dusted off the sand (it was everywhere) from my personal gear and packed up. Then, mindful of blister-producing irritants, I carefully brushed the sand from my feet and toes and put on my socks and shoes. After applying sunscreen and loading my day pack, I thanked Kenny and Paul in advance for breaking down camp, and I headed out.

Just a half-mile or so beyond our campsite, I passed a notch in the foredunes marking the entrance to a four-wheel-drive-only road that leads to Yarborough Pass, a primitive campground on the Laguna Madre side of the island. Many assume that the pass, which was dredged in 1941 and filled back in decades ago, was named after U.S. Senator Ralph Yarborough. It wasn’t; it was named for W. O. Yarborough, a member of the Texas Game, Fish, and Oyster Commission, a precursor of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. But even so, Senator Yarborough was instrumental in the formation of PINS, introducing the initial legislation calling for its establishment in 1958. Ten years later, Smilin’ Ralph, as folks called him, was among the many dignitaries present at the park’s dedication, where Lady Bird Johnson spoke before a reported crowd of 10,000 and then partook in a fish fry and a barefoot stroll along the beach.

A few years after that, my dad and my brothers and I were driving to the Port Mansfield Channel in our brand-new bright orange Ford Bronco when my dad had the idea to escape the soft beach sand, which was difficult to drive on, and make his way to Yarborough Pass via this road, where he planned to take advantage of what he thought would be the more easily drivable mudflats (an endeavor that is forbidden today). When the Bronco, with all four wheels in drive, began to sink in the mud my brothers were ordered out to push. I was young, maybe seven or eight, but I remember the event, mostly because it was the first time I recall my dad cussing—and the only time I remember him cussing for such an extended period of time. The particulars are lost to me now, but we eventually made it back to the beach and down to the channel.

Seashells found on Padre Island.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

A bottle bobs in the Gulf near mile marker 14.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

Seashells found on Padre Island.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

Right:

A bottle bobs in the Gulf near mile marker 14.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

As I continued my walk, the sun grew more intense and the southerly winds in my face were beginning to pick up. The beach conditions were still great, though, and I looked forward to Big Shell Beach which, I told myself, isn’t called Big Shell for nothing.

I knew from studying maps that by the time I had passed mile marker 20 I had entered Big Shell. (There are no signs announcing any of the various beaches.) Sadly, there would have been no way to tell otherwise. This beach looked just like all the others—rich in scenic beauty but nearly devoid of collectible seashells. There were occasional bits of shells that may have been big at one time, but there were no big shells. I continued to come across the usual (and unusual) human detritus—more Mylar party balloons, assorted bottles of varying usages (booze, wine, soy sauce, perfume, etc.), inoperable cigarette lighters, a few more balls and small buoy-type objects that also resembled Wilson, who I continued to greet with enthusiasm. I also passed large tree limbs and tree trunks. Eventually, I did come across some small shells, but few worth picking up.

Though I felt I had found my stride, walking for hours at a time on a beach without shells and the usual throngs of people and canopies and beach umbrellas can get monotonous. Luckily, I find such ambulatory monotony comforting. I’m a walker. I take evening walks around my Austin neighborhood a few nights a week and long walks around Lady Bird Lake almost as frequently.

It’s likely that I picked up this habit from my dad. Even in the early seventies, before the fitness movement had turned walking into a craze, he would have my mom drive him ten or fifteen miles outside of Temple, and he’d walk home. He occasionally remarked that he had enjoyed marching during World War II, when he was in Italy with the Army’s 10th Mountain Division, whose informal motto was Sempre Avanti, Always Forward. And he would sometimes lament the loss of his Army boots, which he had apparently hung on to for a good while after the war. “I should have had them bronzed,” he’d say.

I suspect that my dad liked walking for the same reason that I do. Once my legs are in motion, my mind clears itself of the mundane thoughts that often crowd it—chore lists, grocery lists, calendar entries, lunch options, and, always, looming deadlines. Whenever I walk, my dad always crosses my mind. Would he be proud of me and the choices I’ve made in my life? I think of my kindhearted mother, too. Would she be worried about me, walking all this way? On this particular day I also thought about my late brother, Joe, who was the real outdoorsman of the family. He would have insisted on coming along on this trip—mainly for the adventure, but also for the opportunity to fish. I thought about my wife, Kendall, and Sarah, and reassured myself that they’re both strong women who, even amidst a burgeoning pandemic, can take care of themselves just fine without me.

I also thought about the many, many miles of beach still in front of me.

By this point the wind had picked up and was probably blowing at a sustained 25 miles an hour, with much stronger gusts. On top of that, I had encountered areas where the sand was less densely packed. The combination made walking fairly arduous. I was glad to pass mile marker 25 and see Kenny and Paul up ahead with lunch and a shady canopy.

After refueling on sausage wraps with cheese and resting and shooting the breeze for a while, I started back at it. The wind was still blowing but, hey, Sempre Avanti! People, already scarce, grew scarcer still. During the whole of day two, I probably encountered a half-dozen souls, not counting Kenny and Paul (and the coyote). I’d walk for hours without anyone in sight. I was alone. I was very alone.

Unless we’re counting birds. If we’re counting birds, I wasn’t alone at all. I encountered thousands of seagulls and hundreds of pelicans, as well as numerous sandpipers, including the long-billed curlew, a migrator that can be seen on the Texas shore in the winter. Mixed groups of birds would be loitering at the water’s edge, and as I’d approach they’d get spooked and take off, only to alight a little farther down the beach. It felt like a game, until they’d tire of it and fly off out of sight.

Shorebirds over the Gulf around mile marker 42.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

I saw long-legged egrets and herons, ducks and geese, grackles, sparrows, hawks, and buzzards. The buzzards, always alone, would come gliding at high speed down the trough that runs between the foredunes and the larger sand dunes behind them, taking advantage of the strong tailwind and skillfully riding updrafts that I suspect were created by the foredune. I wondered how they’d learned to do that. And I wondered what they thought of me. Were they waiting for me to drop so they could make a meal of my ample remains? For a moment, I allowed myself to dream: What if I were a bird, able to spread my wings wide, take flight, and ride the winds, instead of having to slog along the beach by foot?

Late in the afternoon, as I, earthbound, plodded winglessly southward, I looked up and out at the horizon and had a somewhat startling sensation: I felt that I was taller—perhaps two feet taller—than my actual five foot ten inches. When I looked back down, the distance from my eyes to my feet seemed greater than usual. It was a strange feeling, but not at all unpleasant. I suspect that the illusion had something to do with the relative flatness of the horizons I was surrounded by—the ocean to the east, the coastal plain to the west, and the long ribbon of sand before and behind me. Much as I sometimes have the uncanny feeling of moving forward in a parked car when the car next to me pulls out backward, my surroundings had played a trick on my inner eye, making me feel like the Big Tex of the Gulf Coast. The Karankawa Indians, among the first known human visitors to the island, were said to have been a tall people, reportedly six to seven feet, which, in my solitude-fueled state of loopiness, made me wonder if I was experiencing a mild case of possession. Maybe I was going a little crazy. I kept walking.

Thinking of the Karankawa prompted me to think, too, about other early inhabitants that followed them. Over the past five centuries this rugged portion of the island has been occupied not just by coastal Native Americans, but by Spanish sailors, Mexican and Anglo ranchers, and the U.S. military.

The Spanish explorer Alonso Álvarez de Pineda first mapped the area in 1519, naming the island “Isla Blanca,” White Island, a nod to the same white sandy beaches upon which I was walking. His fellow Spaniard Álvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca likely passed through the area a few years after Pineda, though there is no evidence that either man had made his way onto the island. In 1543 Spain’s Moscoso Expedition sailed by the island on its way from the mouth of the Mississippi River to Veracruz, but, again, there’s no record of the group coming ashore. A decade later, in 1554, three Spanish vessels succumbed to a storm and ran aground near the present-day Port Mansfield Channel. The Santa María de Yciar, the Espíritu Santo, and the San Esteban carried passengers and crew numbering some three hundred; it is thought that half to two-thirds of them drowned in the accident. Those who made it to shore represent the first documented non-natives to have visited the island.

My Apple Watch informed me that I had set a new record of 361 exercise minutes, which was, apparently, 300 percent of my “move goal.” “Way to go,” the device encouraged me. I was duly encouraged.

More than two centuries later, in the early 1800s, the Mexican priest and rancher Padre José Nicolás Ballí procured the original grant to the island from the Spanish crown, launching the first real settlement of the island. It is from Padre Ballí that the island takes its current name. After his death, in 1829, the land was retained by the Ballí family but sold off in portions over the years.

In the late 1800s, Corpus Christi native Patrick Dunn, who had been a free-range cattleman until the arrival of barbed wire closed off the open range, set up his own ranching operations here. Surrounded by water on three sides, Dunn only needed to fence off the southern end of his sandy spread, which he did somewhere in the vicinity of the current Port Mansfield Channel. As it was for the Ballís, the grazing was good—his cattle fed on the plentiful grasses—and there was abundant fresh water. And though Dunn in 1926 sold his land to Colonel Sam Robertson, who was interested in tourist development, he retained mineral and grazing rights, and the ranching operation persisted for almost a hundred years.

During World War II and into the Korean War, this portion of the island was used by the naval air station in nearby Corpus Christi. Padre Island was, in fact, one of the eight candidate sites for the first nuclear bomb test. (Thankfully, it lost out to a location in New Mexico.)

In the sixties the land was purchased by the federal government, making way for the park that I was now traversing. But remnants of the island’s early uses can still be seen. The ruins of the Novillo Line Camp, the last vestige of the Dunn operation, are located on the inland side of the park at its northern end but aren’t much to see. And unexploded ordnance is still occasionally discovered. Visitors are asked to keep clear of any unidentified metal objects protruding from the ground and report them to a ranger immediately.

Barnacles cling to a television washed up on the beach around mile marker 27.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

A mussel-encrusted soccer ball near mile marker 42.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

Barnacles cling to a television washed up on the beach around mile marker 27.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

Right:

A mussel-encrusted soccer ball near mile marker 42.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

As I walked amid all this invisible and barely visible history, other discarded relics of humanity, both mundane and interesting, made themselves known: hard hats, life jackets, a boxy old television, a scuba fin, a flip-flop with a flower motif, various lengths of rope, a pristine Titleist golf ball, a ping-pong ball, a single Croc covered in barnacles, wine bottles and liquor bottles and beer bottles, a large red barrel, a Tonka truck wheel, and a rusty car rim with the tire still on it; more cigarette lighters; more balloons; and more of everything that doesn’t sink to the bottom of the ocean.

Just before mile marker 35, I came across an enormous loggerhead turtle carcass. Loggerheads can weigh up to 375 pounds and though this one was in an advanced state of decomposition it looked like it might have been that heavy. As I examined it, I could see no obvious outward cause of death, no large gashes from a boat propeller or entangling netting or fishing line, and I chose to think that the big seafarer had lived out its full seventy-to eighty-year life span swimming the oceans, happily cavorting with other sea creatures, and munching on shellfish at will—a good life. I thought about my own life for a moment, and while I’m pretty sure that I’ve been living my best life for the past 53 years, I was certain that I was doing so that day.

At about seven o’clock, not long after I passed the turtle’s carcass, I strolled into camp. Kenny and Paul had chosen a lovely spot, again at the foot of a tall dune. After prying off my shoes and enjoying a hard-earned cold Modelo, I was informed by my Apple Watch that I had set a new record of 361 exercise minutes, which was, apparently, 300 percent of my “move goal.” “Way to go,” the device encouraged me. I was duly encouraged.

I was discouraged, however, by the meager collection of shells I had in my possession. There were a few colorful fragments, a couple of common arks, a sea bean, one fairly impressive cockle, one Florida spiny jewel box, a nice disc dosinia, and a cool specimen of brown sea glass, likely a piece of a beer bottle, upon which the faintly legible words “Law Forbids Use of This Bottle” were visible. Again, there would always be tomorrow.

As we clambered to the top of a large dune to watch the sunset, the sense of remoteness and isolation had intensified. We were a long way from anywhere. It was 35 miles back to the park’s visitors center, which was closed, and 25 miles down to the Port Mansfield Channel, which was a dead end. Inland, somewhere out there across the Laguna Madre, lay the 825,000-acre King Ranch and, save for a few tiny communities, a whole lot of nothing. Cellphone service had been nonexistent since midday the day before, but suddenly, while I was atop the dune my phone started lighting up with messages and notifications. I had mixed feelings about making contact with the outside world. I did check the PINS Facebook page for updates, though. The Malaquite Campground would be closing until further notice due to the coronavirus.

The dunes at sunset.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

After dinner, we sat around the campfire drinking and talking. It was still windy and a bit more overcast than the night before, but the opportunities for good stargazing were again plentiful. Venus, fairly low and exceptionally bright in the northwest sky, was always first to make an appearance. And then before you knew it, the entire sky filled with stars. The Milky Way was so bright it resembled light cloud cover.

As I sat, I assessed the status of my physical well-being. I had walked forty miles in two days and this day had been more difficult than the day before. Sometime after lunch, I had stopped for a brief rest and taken my shoes off to wade in the water and walk barefoot for a while. Varying the foot feel, as I came to refer to it, seems to help with foot fatigue. I had walked too far barefoot, though, and felt a slight pang on the ball of my right foot. I feared a blister was forming.

Other than that, I was at worst a little tired and mildly sore. I only had 25 or so miles to go. I felt confident that I was going to make it to the end, possibly even the following day. I mixed another paloma. Midnight was approaching.

And then, as we were getting ready to call it a night, we noticed headlights bobbing toward us from the north. It was late for fishermen—late for anybody, really. The truck passed right by us. But then it came to a sudden stop and backed up. We approached cautiously. A man, who appeared to be by himself, opened his door and got out. He was lanky and seemed somewhat addled. From the other side of his truck he asked in an excited voice, “How far to the end? How far to the cut?” “Twenty-five miles,” we replied in unison. That was all he needed to know. He zoomed off into the darkness.

Day 3

March 25

MM 35 – MM 55

Once again, I awoke at sunrise. Although I was miles past Big Shell Beach, I held out hope for better shelling ahead. A few miles into my walk, somewhere around mile marker 40, I came upon a small shack tucked into the dunes. It was the Sea Turtle Patrol Base Camp. In less than a week, park personnel and volunteers would begin their annual four-plus months of relentless patrolling of the beach, looking for the telltale check-mark tracks and signs of nesting Kemp’s ridley sea turtles. Those assigned to these far reaches of the park or working the night shift sometimes opt to bunk in this simple plywood structure. But for now the building was empty.

As I walked on, I started to see more small shells, though nothing too eye-grabbing. I passed some fishermen who had just baited a line with a large stingray and were about to paddle it out by kayak to deeper water. They were angling for sharks. We exchanged nods. I also passed large hunks of marine debris: a massive, rusty storage tank covered in colorful graffiti from visitors past; an overturned boat about fifteen feet long, memorialized by a plastic hard hat atop a long pole driven into the sand. A bit farther on, I spotted a wooden cross in the dunes that appeared to be the final resting place of a beloved pet named Beau Dog. Soon I passed a lone fisherman, a friendly young guy named Noe, from nearby Calallen. He fishes the surf here often and on this day was hoping to land some pompano, one of the Gulf’s tastiest denizens. The water, cool, clear, and green, was ideal at the moment but wouldn’t last, he said. We talked for a little while—he seemed bemused by my adventure—and soon parted ways.

Not long after, I encountered a few more fishermen, all northbound. We exchanged quick waves but nothing more. As with the buzzard, I wondered what they must have thought of me, walking alone in this desolate place.

I rendezvoused with Kenny and Paul in the vicinity of mile marker 45, where we scarfed down a lunch of chicken tacos, and I got some rest before shoving off again.

Mile marker 45 on Padre Island National Seashore.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

The shelling continued to disappoint. I began to think that I was going to beachcomb a 65-mile stretch of mostly untrodden barrier island and have little more than sore muscles, blistered feet, chapped lips, chafed nether regions, and a mild sunburn to show for it. It just didn’t seem possible.

As I passed mile marker 50 later in the afternoon, I kept an eye toward the sea, at a spot where in 1912, six months and one day after the Titanic went down, the SS Nicaragua, a Mexican cargo ship on its way from Tampico to Port Arthur with a load of cotton and other freight, ran aground in a hurricane, stranding some twenty crew members. The ship’s boiler is still visible when the tide is low: a boxy black structure barely protruding from the breakers about a hundred yards out. It wasn’t much to see, but as I walked on, I thought about the castaways who had hoofed it the 54 miles from here to Port Isabel.

The Nicaragua isn’t the only ship to have met mishap on Padre Island. There have been many, particularly in this area, where there’s a point of tidal convergence at a slight bend in the coast that has come to be known as the Devil’s Elbow. The most famous are the aforementioned Santa María de Yciar, Espíritu Santo, and San Esteban, whose foundering in 1554 was the worst calamity the Spanish fleet had experienced in the New World. They are also the oldest shipwrecks ever found off of the U.S. coast.

In 1967, the wrecks were discovered by a private out-of-state salvaging company and the long battle over rights to the find, which included gold and silver and various artifacts, ultimately led to the enactment of the Texas Antiquities Code in 1969.

By coincidence, right around that time, the members of the troubled Courtney Expedition—the one involving the bright orange Bronco and my dad’s profligate cussing— “discovered” a grounded shrimp boat in the waters just offshore. This wreckage held no riches but, if memory serves, provided the expedition’s members with the opportunity to swim out to it and swing off of a rope dangling from one of the damaged vessel’s yardarms.

Reeling in my decades-old memories, I came upon a treasure of a different kind. There, on a beach that didn’t even include the word “shell” in its name, was an enormous patch of enormous shells, and some medium and small shells, too. It was as if the beach itself was made up of nothing but shells. I could have taken a shovel to it and overturned nothing but shells.

I was dazzled by the quahogs, large clamshells similar to cockles but with a much sturdier build, plus all sorts of interesting striations. There were orange and brown ones, gray and white ones, tan and white ones, gray and bluish ones, orange and yellow ones, and blackish ones. They were big and beautiful. And it had only taken about 55 miles of walking to find them.

I reluctantly winnowed down my haul to a dozen or so specimens, slipped them into my knapsack and moved on. And then, not much farther along, I stumbled on another such patch. There were more quahogs, and other shells, too—tiny arks, a common sundial, and even a large vertebra from some unknown species. And there was another patch after that. The beach, from the water’s edge all the way back to the dunes, was littered with shells. Soon my pack was brimming. As I walked further, something ahead caught my eye. Was it a lightning whelk, I wondered, or merely another “false whelk,” deployed to cruelly get my hopes up? It was, in fact, a lightning whelk, and a big one at that. It was weathered, but it was a lightning whelk nonetheless. In the last five miles of my third day, less than ten miles from the end of the line, my fortunes had suddenly and dramatically changed.

There, on a beach that didn’t even include the word “shell” in its name, was an enormous patch of enormous shells. It was as if the beach itself was made up of nothing but shells.

As seven o’clock approached, I spotted Kenny and Paul. We had decided that rather than complete the trip in the dark, a somewhat risky proposition, we’d camp for the night near mile marker 55, which would leave for the morning a victorious sprint of just five miles.

When I reached the campsite, I felt a sense of exhaustion and triumph the likes of which I can’t recall. My body was sore and my feet were blistered, but I couldn’t have been happier. I popped open a beer and unloaded my booty. Kenny and Paul were duly impressed. Driving the beach, with sea-mist-covered windshields, they’d missed the honey holes completely.

I took a restorative swim and toweled off. We enjoyed beef fajitas for dinner, and ranch water cocktails and beer. As was now our evening ritual, we climbed a tall dune to watch yet another beautiful sunset. And as had happened during our previous forays, the Gulf croton, a pretty pale-green dune plant that smells like eucalyptus, put me in mind of my earliest childhood explorations, and of my mom, who used to bring small clippings back to the condo for simple arrangements.

The night sky above Port Mansfield, as seen from the top of a dune near mile marker 55.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

As we sat around the campfire, the sky was clear and dark, and the stargazing was the best it had been the whole trip. The Milky Way was aglow from one horizon to the other. We saw shooting stars and satellites whizzing across the sky. We got into an intense debate about whether a particular bright light out over the water was a star or some seafaring vessel. It was so low, it had to be a ship, I argued. We consulted a stargazing app on Paul’s phone and discovered that it was, in fact, Menkent, the constellation Centaurus’s brightest star. I was duly humbled.

The light from Corpus Christi was undetectable here, but now there was visible light from the southwest—the Brownsville-Harlingen metro area, I figured. We climbed back up the dune to see what we could see in the dark. As we crested the sandy mound, we were surprised to see the city lights of Port Mansfield, twinkling just a few miles away. We could see radio towers, something that might have been a small airport runway, and the flashing lights atop the giant turbines of the Penascal Wind Farm. Then, looking south, I saw more flashing lights, just offshore. At first I thought they were fishing boats, but peering through binoculars I realized that they were the green and red markers at the end of the Port Mansfield Channel’s jetties. They were so close, just five miles away, at the terminus of my long trek. Up on that big dune at night, tired and with a few beers and some tequila in me, I almost got a little emotional.

Day 4

March 26

MM 55 – Port Mansfield Channel

There’s no point in denying that my last day was anticlimactic. I had only 5 of my 65 miles left to go and there was nothing left to prove, really. I had already experienced the quiet and introspective grandeur of solitude and the frustrations of seashelllessness and then the joys of belated seashellfullness. The two or so hours I had left were a formality, like the last few minutes of a great dinner party, when everyone tries to find their coats and thank the hosts and say goodbye to their fellow guests and reluctantly find their way out the front door, hoping that no moments of awkwardness sully all of the merry vibes.

When I woke the ocean water was again too green, too clear, and too inviting to pass up. Once again, I leaped in, though this time, with my leg muscles stiff and sore and both of my feet blistered, I limped more than leaped. Still, I emerged exhilarated. I downed a quick breakfast of trail mix and an orange, this time with a side of ibuprofen, washed down with cold brew coffee. Then Kenny and Paul wished me luck as, for the fourth morning in a row, I pointed myself south and started walking.

The sun broke through the clouds early and the sky opened up. It was the brightest day of my trip, and I soaked it all in. I looked out at the Gulf of Mexico, so vast. I looked at the tall sand dunes. I turned around and looked up the shore northward and then looked ahead southward. I also cast my gaze downward. I still had a little beach left to comb, after all, and I soon came upon another rich deposit of shells, yards long and brimming with more large and colorful quahogs. I picked up a few choice ones and put them in my pack. To my surprise, I had not seen one intact sand dollar the whole trip. But in that last mile or so I found three nice ones.

The thousands of huge pink granite blocks that form the jetties of the Port Mansfield Channel and the southern end of the Padre Island National Seashore were visible now, protruding far out into the Gulf. Across the channel I could see the southern portion of the island. As I made my final approach, the beach between the shore and the foredunes widened out, a result of the decades-long effect the jetties have had on the currents and tides that shift the sands. The dune grasses waved in a welcoming fanfare and my bird friends, still up for a game of catch-me-if-you-can, provided an aerial escort. Kenny and Paul were there waiting for me. And so too was one other solitary soul, a young man who, accompanied by his dog, had dragged a small camper all the way down the island to escape the pandemic. He had talked with Paul briefly but seemed content to maintain a healthy distance. He looked on curiously as I bent over and kissed one of the jetties’ warm and salty granite blocks.

I had walked for three and a half days, from Kleberg County, through Kenedy County, and into Willacy County. I was tired and my body was sore, but inside I felt as tall as a Karankawa. I was happy. I had made it.

As a sort of ceremonial exclamation mark, I made my way over the jetty’s 2,000-plus feet of bulky and uneven blocks, all the way out to the tip of the north jetty. It quickly became evident that because of my blistered feet this was not a great idea, but I proceeded foolheartedly. After about twenty minutes of painful traversing, I stood at the end beneath a rusty post atop which was one of the flashing lights that I had spied from the dune the night before. It was a good vantage point and I snapped a few photos of the southern portion of the island and the familiar northern portion too.

The author takes an early morning dip around mile marker 40 on March 25, 2020.

Photograph by Kenny Braun

When I got back to the beach, I swam in the cool water and snacked on the food we had left. Paul tried his luck fishing but struck out, and Kenny paddled out and surfed for a while. Then the time had come. We loaded up our two vehicles and, for the first time in four days, headed north.

We drove along the beach for forty miles before we encountered another human being, and as I sat at the wheel of my Toyota, getting reaccustomed to the small comforts of modern automotive technology, I found myself rolling the trip around in my mind. For the better part of four days, sand beneath my feet and also in nooks and crannies I wasn’t even aware of, I had hewed the border between the coastal wilderness of South Texas and the aquatic wilderness of the Gulf of Mexico, between Padre Island’s colorful past and a preserved portion of its largely unchanged present.

On the surface, my long walk was a physical ordeal. But the minor aches and weariness aren’t what have stuck with me. What has stayed with me—and will stay with me for years to come—is the profound sense of just how lucky I’ve been to get to spend so much of my life amid such a natural wonder.

No, the Texas coast doesn’t have the finest beaches in the world. You can’t snorkel in crystal-clear water or surf a flawless point break or explore sea caves by kayak here. But it is a place where, on the Easter weekend following my trip, the first Kemp’s ridley sea turtle nest of the year was found, a place where the next generation of turtles will, fingers crossed, begin their lives. Sempre Avanti! It’s a place where a person can not only fish and swim and spend time with family and old friends, but, if he’s so inclined, point himself south or north and walk an absurdly long distance, with nothing but his memories—and many, many birds—to keep him company. It’s a place I love, Mylar balloons, inoperable cigarette lighters, barnacle-covered flip-flops, and all.

This article originally appeared in the August 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Beachcomber.” Subscribe today.

Recent Comments