Monday, 24 February 2020, 3:30am. Cape Legoupil, Antarctica

The weather window of 24-36 hours has passed and I am still here. Reduced to a walk and with the snow coming in sideways, I have had to make camp. Now, I can barely stand up outside the tent. The glacier is at the centre of a blizzard, with gusts of more than 90mph. There is nothing to do but wait. For how long, I don’t know. It is no longer a race, it is survival.

Wearing only a pair of black trunks, he plunged into the still, dark water below. The temperature was barely 1C. Thirty-five seconds later he clambered, shaking and gasping, back onto the boardwalk. This wasn’t the start of his training, but it was the work that would come in most useful.

The aim of Project Iceman was simple. Hofman was seeking to become the first human to complete an Ironman triathlon – a 2.4-mile swim, a 112-mile bike leg and a marathon – in the least appropriate continent for such a feat; Antarctica.

The preparations alone were, to say the least, complicated. The 28-year-old had to assemble a team to guide, support and document his attempt on what is a largely uncharted land mass. He had to find kit that would allow him to run, cycle and swim without perishing in the extreme cold. He had to find sponsors to fund the expedition. And finally he had to prepare himself.

At least it was not Hofman’s first Ironman. A keen footballer and fitness enthusiast, he completed one in his home city of Copenhagen in 2016, ticking it off among a bucket list of athletic challenges. He didn’t catch the Ironman bug though, and thought it was the end of his triathlon career.

But then, two factors coincided to bring him back to it. First, Hofman began work for a start-up that used artificial intelligence to help triathletes tailor their training. With the sport forefront in his mind at work, he then stumbled across a video online. It featured fellow Dane Nick Jacobsen kiteboarding off the helipad of a Dubai hotel, the sky-scraping five-star Burj Al Arab. It was the highest kiteboarding jump ever.

Hofman wanted his own piece of history. But he also wanted to push his psychological boundaries as well as triathlon’s physical frontiers.

“I’m not a big fan of the cold or the disciplines of triathlon themselves,” he tells BBC Sport.

“But I like that it is a training of the mind, of mindfulness and how you overcome.”

And that is why, along with hours of training, trips to specialist sub-zero chambers, Greenland, Iceland and Norway, he went for his early-morning dip in Copenhagen harbour.

Over the course of the next six days, he repeated the test. Each day he attempted to stay in longer.

When he got out of the water on day seven, his face drained ghostly white and his body blotched red by broken blood vessels, he had managed 11 minutes and five seconds.

“My body could not have changed that much over seven days,” he says. “It was really just staying in control of your mind when your entire body and system is under extreme stress.

“We can do more than our minds let us believe.”

Saturday, 22 February 2020, 5:30am. Project Iceman startline, Antarctica

We left Copenhagen 20 days ago. Flight to Frankfurt, onto Buenos Aires and then to Ushuaia on the southern tip of Argentina. A week at sea, another week at Bernardo O’Higgins – the Chilean Antarctic research base – and now, finally, I am standing on the start line. It is a clear morning, only a slight current, two support boats ready, perfect conditions for the swim. It begins.

As Hofman dived into the Southern Ocean, the crew on one of his two support boats were focused only on the possibility of him being joined by a far better, bigger swimmer.

Leopard seals can grow to 3.5m long, weigh 500kg and swim at speeds of 25mph. In 2003, one attacked and killed a British scientist diving in waters off Antarctica.

While his support boat was poised to haul him aboard at the first sign of danger, Hofman was wrestling with his own demons.

“For the first kilometre, my subconscious was just trying to get me to give up,” he says.

“It was saying that this is a bad idea, it is too far, it is too cold, that the whole thing makes no sense.”

That foreboding gave way to a trance-like state that even a trundler in a leisure centre experiences from time to time; the brain lulled by the rhythm of the stroke, the distance softly eroding away.

And then, with his view alternating between inky depths and the polar heavens, Hofman spotted land. Nearly two-and-a-half miles of sub-zero water was behind him, glacial ice was finally back under his feet and his least favourite of the three disciplines had been completed.

With his bare hands and feet first numbed by the cold and then buzzing with the pain of returning blood, it took 30 minutes to switch kit. It took another 20 minutes of walking to revive his frozen legs. Finally he was on his bike and pedalling through the snow.

As the first 5km breezed past, his mind wandered to what it would be like to finish. The second 5km made him think he never would.

It lasted two hours; his average speed did not reach 2mph, his journey punctuated by deflating falls. As the morning had worn on, the rising, warming sun had left Hofman ploughing through a treacherous, energy-sapping sludge. The ice was not the only thing melting down.

“I wasn’t exhausted at that point, I had only been going four hours, but the distance and time still remaining was so difficult to comprehend,” he says.

“Looking from the outside, everything I was doing was really slow. But in my mind everything was racing – there was the physical challenge, the frustration that I was not going faster and all the negative thoughts intruding.”

Hofman was caught in a twin-speed world. His mental state and emotions manically darted about in his head while his bike edged painfully slowly across a whiteness perma-lit by the mid-summer sun.

To keep control, he deployed the tactics he had used in Copenhagen harbour a year before. In the water, he had counted his breaths – groups of 60 before starting over – to break down time into comprehendible chunks.

In Antarctica, he focused only on chalking off the next kilometre.

After 27 hours in the saddle, without a wink of sleep, he still had 60 of those kilometres still in front of him before he could begin the marathon.

“I started doubting whether I could actually finish. That was my ultimate low, physically and mentally – I’m not sure if I will get to that point in my life again,” says Hofman.

“The whole message behind the project was that limitations are only perceptions, but I don’t think I realised I would have to break my own, as well as other peoples’.”

With the cold suppressing the hormones that stimulate thirst, Hofman’s support team took on the job instead, forcing him to hydrate at hourly intervals. As he battled on, another factor became a threat.

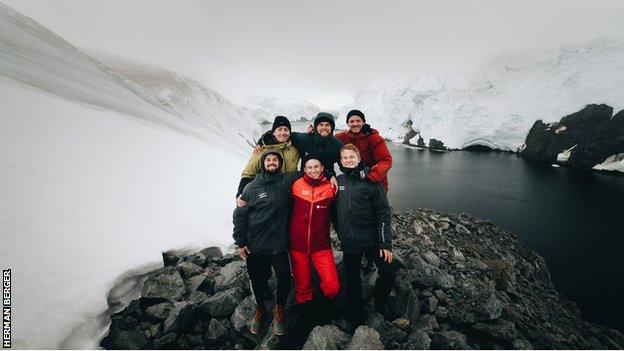

Hofman’s team – which included expert Antarctic guides, as well as photographers and filmmakers from Denmark, the United States and Norway – had allowed a day and a half for the attempt.

Considering he had done a half-Ironman in the Arctic Circle in fewer than 11 hours, it seemed a reasonable estimate.

But with the attempt well behind schedule, their window of mild weather was closing.

By 1:30am on Monday morning, 44 and half hours since the start but with more than half of the 26-mile marathon still to complete, Hofman was forced to take shelter.

His run had become little more than a stumble as the wind and snow whipped around him. With supplies dwindling but the finish relatively close in distance if not time, all but one of his guides was evacuated.

Hofman and his remaining companion made camp. And waited.

“The conditions were so crazy, but, isolated on the glacier, we couldn’t move anywhere,” explains Hofman.

“Had we been back at the Chilean base, we probably would have cancelled the attempt. But we had no choice but to wait it out. Having got so far, I wanted to finish it, whatever it would take.”

Hofman spent 27 hours huddled in the camp, spinning out his food and waiting for the weather to pass.

Eventually the wind dropped, the snow stopped and he emerged to claim an eerie, quiet victory over the elements and the awesome mental and physical task he had set himself.

“In the end it took me just less than 73 hours,” he says.

“It was a surreal feeling. At times it felt like it was never going to end so it was difficult to grasp that it was done.

“It was a crazy big sense of relief because it was way beyond what any of us had predicted as a worst-case scenario.

“But there is no physical finish line, like in a regular Ironman or triathlon. Just suddenly I was there, with the same guys on the same glacier, but finished.”

Tuesday, 3 March 2020, South Atlantic Ocean

I hadn’t thought further than the Iceman. But as soon as I finished on the glacier I was done with ice, snow, and being cold. I just want to be home. I have told the team, I am done. But we are still at sea, still a week away from Ushuaia in Argentina, 10 days away from Copenhagen, still communicating with the outside world only by occasional texts and emails.

When he docked in Argentina, Hofman realised the world was a different place to the one he had left behind.

Back then, in early February, coronavirus was confined mainly to China. The biggest outbreak outside of its borders were 61 cases on board the Diamond Princess cruise liner, quarantined off the Japanese coast.

The term Covid-19 was yet to even be coined by world health officials.

On his return to Ushuaia in Argentina on 10 March however, a wave was breaking over Europe. Italy was in lockdown after hundreds of deaths while Spain, Germany and France were all reporting more than 1,000 cases.

“We had been completely off the grid,” remembers Hofman. “We hadn’t had any internet connection since we first set sail from Argentina, with only the odd text from home.

“That was the first time we realised the seriousness of the situation – it was all over the news.”

It was the starting gun for a new, unexpected race.

The Prime Minister of Denmark was publicly discussing whether to close the country’s borders. Flights were being cancelled. The surprise party Hofman’s friends and family had planned was already postponed. Briefly it looked as though the guest of honour might be indefinitely delayed.

Hofman made it home 11 hours before a ban on foreign citizens entering his country came into effect. Now as he looks back – from 35 seconds in Copenhagen harbour to 72 hours at the end of the world – he thinks his experience can help those suffering in these most extreme times.

“The mindset can be applied to every part of life,” he says. “A lot of things we are dealing with are filled with uncertainty and our goals may seem far away right now.

“It can be tough to be content and comfortable with yourself and keep going in the face of intense challenges.

“But dividing our journey into smaller chunks and not being overwhelmed by the distance still to travel can help you get there.”

Recent Comments