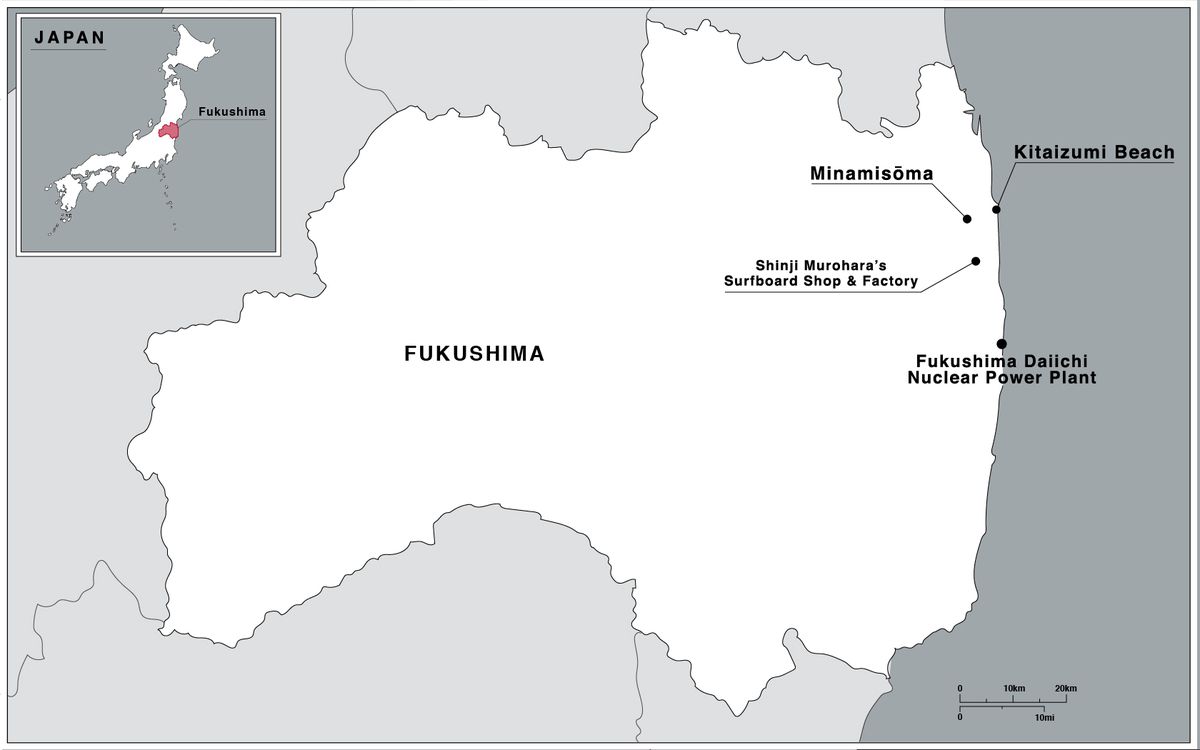

Shinji Murohara sits in the cluttered office of his surfboard factory at the edge of Odaka, a sleepy seaside town nine miles north of the now-decommissioned Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station. The 52-year-old local surfing legend leans back, dressed in his signature groutfit: head-to-toe heathered gray sweats and silvering fringe around his temples to match. His eyes are deep-black, his verbal cadence quick and choppy. He gestures to the room next door, telling a story he’s told a thousand times before.

”It felt like a movie,” Murohara says, shrugging. “No one can understand except for the people who experienced it.”

Next door is the shaping room, where giant foam blocks are shaved down to sleek ovals, and where Murohara was at 2:46 p.m. on March 11, 2011, when a 9.0-magnitude earthquake bloomed from the Pacific Ocean floor and triggered the most devastating tsunami in Japanese history, causing the Daiichi power plant to explode.

On the morning of the triple disaster, surfers bobbed in the water, nine miles from Murohara’s shop. They felt the water flatten and recede, a harbinger, and scrambled from the ocean up the nearby hill where a shrine and playground complex sit. From their perch they watched the waves return, bigger and bigger and bigger. They survived, but the world around them crumbled and broke.

For five minutes, Japan shuddered in violent spurts as the Tōhoku fault gave way. Tremors ripped all the way to Beijing, and sent large ocean waves 5,200 miles to the California coast. When the earth settled, Japan had shifted 7.9 feet closer to the U.S., and a 250-mile stretch of the coast dropped two feet.

Murohara shook off the dust. Neither his two-story surfboard factory nor his childhood home, just a stone’s throw away, were badly damaged. At first, he figured business would go on as usual, earthquakes being relatively common in Japan and elsewhere along the Pacific Ring of Fire. Twenty-four hours after the disaster, Murohara heard for the first time that the power station had leaked radiation.

Murohara leans forward, placing his elbows on the table and palms together as though in prayer. He never could have known that what unfolded in the wake of March 11 — the government’s fumbles, the media’s hunger, the tens of thousands of lives lost and displaced — would turn his vibrant ocean community into an empty shell, haunted to this day by misinformation and fear.

“If Fukushima was a book,” he says, “the cover would be about radiation. But the contents would be totally different. Of course, people never read the contents. It’s our job to change this.”

The story of modern-day Fukushima arguably starts in the 1950s, after American soldiers dropped the atomic bombs but before they brought over their surfboards during reconstruction duty. Surfing was introduced to Japan in a sweet spot of its history, when new technologies and a flood of Western media ignited visions of never-ending progress and wealth.

Fukushima’s waters are coldest in March, when snowmelt from the Yamagata mountains flows into the rivers and creeks that wind through farms, towns, and factories as they journey to the sea. In Odaka, where freshwater combines with salt, life reflects the constant negotiation between the ocean’s meditative qualities and its deadly force.

In most places, the Fukushima coast is now, as elsewhere in Japan, buttressed by a concrete wall — 30 feet high, miles and miles and miles long. Giant concrete tetrapods are scattered across the beach floors, manipulating the surf. After the tsunami, defenses were not only rebuilt but enhanced. Just one strip of unadulterated sand remains, hugging the eastern point where surfers like to gather.

As Murohara was resettling in Odaka in 2016, he had seen dramatic international headlines that exaggerated or mischaracterized the water’s danger. Headlines like Wavelength Mag’s “The Fearless Surfers of Fukushima,” Al Jazeera’s “Fukushima’s surfers riding on radioactive waves,” and the Daily Mail’s “Japanese daredevils brave the contaminated water and sand.” Once people were allowed back in the region, sensational media flooded the internet — like photos of flowers, purportedly mutated by Fukushima Daiichi’s radiation, but actually photoshopped.

In Murohara’s telling, the book of Fukushima would begin not with the faulty nuclear plant, nor the aftermath of the accident, but in the early 2000s, back when Fukushima’s surf culture was deepening its roots and the local economy was flourishing from the surf-tourism campaigns he’d helped orchestrate. He would not linger on the ways in which Odaka, now polished clean of radioactive fallout and reopened to businesses, is still struggling to rebuild after the evacuation.

Murohara wouldn’t belabor the fact that Odaka’s population has dropped from 13,000 to 3,000, nor that the 15-minute drive from his home to Fukushima’s best waves, at Kitaizumi Beach, is filled with reminders of what once was: thigh-thick bamboo and a towering pine forest now littered with buried watermelons, lures for radioactive monkeys and wild boars; shiny solar panels occupying abandoned rice paddies and lots where homes used to stand; boarded buildings separating the one laundry service and two hardware stores on main street; how the only reopened guest house, once full of dripping wetsuits, is now empty some nights. At Kitaizumi Beach, there used to be a campsite where surfers and families hung out, and a restaurant that fed hungry bellies, and a public hot spring that welcomed tired bodies. Now, it’s a parking lot with bathroom facilities and some planted saplings.

Murohara would rather highlight the new grocery store and food hall/community center, where you can now buy Murohara Surfboard Productions (M.S.P.) longboards and shortboards after slurping down a steaming bowl of ramen.

He’d note that M.S.P. was one of the first local businesses to begin employing people in 2016 when residents were given the all-clear to return, and how he’s currently in the middle of doubling the space of his production facility to make room for new contract work manufacturing boards for Mayhem and Murasaki sports, North America and Japan’s biggest surfboard producers, respectively.

Though Odaka’s streets may pulse like a weak heart, he’d wax on about the upcoming international surf events that he and his partners at Happy Island Surf Tourism — Fukushima translates to “Happy Island” — have planned at Kitaizumi this summer, where extra-wide stairs extend across the length of the seawall that faces the beach like tiered amphitheater seating, perfect for watching the sunrise, or surfers ripping on waves.

He’d acknowledge that while the ocean caused incalculable damage — killing 2,000 people in Fukushima and 16,000 more elsewhere in Japan, destroying hundreds of thousands of buildings, and causing radiation to poison homes, farms, water supplies, and animals — the ocean has also helped people heal and finally feel at home again. To Murohara, the real story of Fukushima is a story of rebirth. It is a story about the weight of physical and mental trauma, of deception and unshakeable stigma, and how a destructive force can be channeled into regenerative power.

Prior to 2011, Fukushima was nationally famous for its rice, sake, farm-fresh vegetables, and horse sashimi, but, most of all, for its samurai history. Every summer since the 1300s, a military-training-exercise-cum-festival tournament has taken place in the giant grass field in south Minamisoma City, the ruling municipality for Odaka and Kitaizumi Beach. For three days, tens of thousands of spectators cheer on a reenactment of warriors from one of Japan’s most iconic eras. In one event, men wearing traditional samurai armour race horses around the dirt track; in another, men clad in all-white cloth capture wild horses with their bare hands.

In its recovery from World War II, Japan rapidly expanded its industrial base. Factories and manufacturing centers sprung up in Fukushima, which is located in convenient proximity to Tokyo and swaths of open land. The prefecture had already been supplying Tokyo’s metropolis with resources, namely energy, since the late-1800s, when coal mines were bored into the landscape. However, the island-nation’s finite natural resources dwindled as decades passed, and the need for alternative energy grew. Despite experiencing the devastation of nuclear weapons in 1945, Japan turned to nuclear energy.

Framing the effort as a means to peace and modernity, the Japanese government began investing in nuclear power in 1955, constructing its first nuclear power station in 1961. That same year, town councils near Odaka agreed to invite the Tokyo Electric Power Company and the new American light water reactor to their coastline. The system was hailed as simpler, safer, and cheaper than the alternatives, and citizens were assured that the 10-meter sea wall would protect them against worst-case natural disasters. Using Fukushima’s waves to help cool down the reactors, the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station opened in 1971, and the plant was shipping energy to Tokyo in time for the last coal mine to shutter in 1976.

By early 2011, Japan was generating 30 percent of its energy via 54 nuclear plants, second in the world behind France in terms of percentage of electric power supply. Japan’s plan, according to a report from the World Nuclear Association, was to boost that number to 50 percent by 2050.

As Japan was implementing nuclear power infrastructure, surfing was gaining popularity around the globe. Starting in the 1950s, images of people surfing trickled into Japanese media. The 1959 surf movie Gidget — a Sandra Dee romance about a blonde, spunky teenage California girl — is widely credited with piquing mainstream interest in the sport all over the world. In the early 1960s, American troops deploying to Japan brought their surfboards with them, passing along surfing techniques by word of mouth. By the 1970s, surfing had sunk its teeth into Japanese culture, with more than 50,000 surfers riding waves along every available coastline.

However, surfing wasn’t afforded the same welcome to the shores of Japan as nuclear power. While the big, economic engines of nuclear power stations were received with relatively open arms, surfers were stereotyped in the same vein as hippies: lazy and unfit for serious societal demands. Left to themselves, surfers separated into tight-knit clans up and down the coasts, from the southern beaches of Miyazaki to the northern stretches of Hokkaido.

Among those who know surfing in Japan, the break at Kitaizumi Beach is considered the best within 100 miles, and the most consistent in the entire country. If it hadn’t been for the 2011 triple-disaster, one of Murohara’s colleagues, Hideki Okumoto, is positive that Kitaizumi Beach would have been chosen as the site for surfing’s inaugural Olympic competition in 2020.

Okumoto, a dynamic and fast-talking professor of economics at Fukushima University, has worked with Murohara on local surf-tourism campaigns since the early 2000s. Around that time, Okumoto was invited to advise Minamisoma City’s government on the region’s failing industrial economy. While everyone was trying to figure out how to resuscitate the electronics and auto factories that had been keeping them afloat, Okumoto, a longtime surfer, recalls telling the mayor, “‘You don’t know the real resource of this city. This area has a good wave and a good beach — it’s a good resource for this city.”

By 2004, Okumoto and Murohara had formed a nonprofit together, Happy Island Surf Tourism. Both men were assigned to a city-backed committee, alongside representatives from the chamber of commerce, tourism office, education department, and hotel association.

Local surfers were enlisted to help clean up the beach, and became de-facto brand ambassadors for the area. Seeing this, city officials began to reconsider their perception of surfers. The interdisciplinary committee was eventually given a $200,000 budget for work on Kitaizumi Beach, which they used to hire long-overdue lifeguards. “It was the first time in all of Japan that surfers got taxpayer money from a city,” Okumoto says.

Their initiatives worked. According to the tourism office, Kitaizumi’s summertime beach attendance swelled from 54,000 people in 2005 to more than 84,000 people in 2010. Murohara and Okumoto organized national and international surf competitions, attracting the all-holy World Surf League in 2007, which brought stars like John John Florence to town for a qualifying event. For the first time in Minamisoma City history, hotels reached full capacity.

As Kitaizumi Beach started to register internationally, so did local surfers. “In this area, there were many kid surfers, but they didn’t want to be pro surfers because they couldn’t imagine it. But when big contests came here, they thought for the first time, pro is so close to them,” Okumoto says. “They could imagine it.”

Throughout 2010, Okumoto planned to create a surf village in Odaka. The idea was to pair young surfers with older farmers to help with fieldwork in exchange for room and board, and also attract retired city folks who wanted to live a second life in a vibrant seaside community. Just as that plan was coming to fruition, however, Fukushima was struck by a horror they had been told was impossible.

On March 11, 2011, a 46-foot wave flooded the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. It cut electrical power and disabled its diesel backup generators. While the four seaside reactors were immediately and successfully shut down, the loss of all power obstructed necessary cooling procedures. Over the next five days, failure after failure occurred, until eventually, a hydrogen-air mixture built up and exploded in three of the four reactors. Then three of the four reactors experienced fuel-rod meltdowns. The final explosion happened March 15.

During this five-day window, chaos unfolded across the country, and public information was hard to come by. On the evening of March 12, Murohara received orders to evacuate via radio broadcast, but the town-wide announcement didn’t contain many details. He knew the orders were due to radiation concerns from the power plant, but he didn’t know how serious it was, how long he’d be gone, nor what the potential harms were. He packed a few days worth of clothes and drove himself and his cat, Lan, up to the western Yamagata mountains, where he could soothe his anxiety with snowboarding. Both TEPCO and the national government, which owns a majority share of TEPCO, issued press releases over the ensuing days, but each one was vague. Some people hid in their homes and refused to leave. Some people left the country immediately.

Slowly, it dawned on Murohara that he wasn’t going to be let back into his home anytime soon. Though all the roads to Odaka had been closed, he snuck into town anyway and gathered more of his things, including his surfboard.

Like everyone around the world, Murohara had questions no one would answer. Friends and family were missing, but no one was allowed to search for them. Unlike other coastal areas that had been hit hard by the tsunami, the firefighters and rescue crews in Fukushima had only the first few hours of March 12 to search for people who had been swept away by the ocean’s waves before they, too, were evacuated and barred from reentry. The towns on the periphery of the power plant — Namie, Okuma, Futaba, and Tomioka — were inaccessible for the next seven days while TEPCO sorted the situation. In some of the adjacent coastal towns, injured people who weren’t evacuated within the first day were left to die, friends and family abandoned in the wake of the waves.

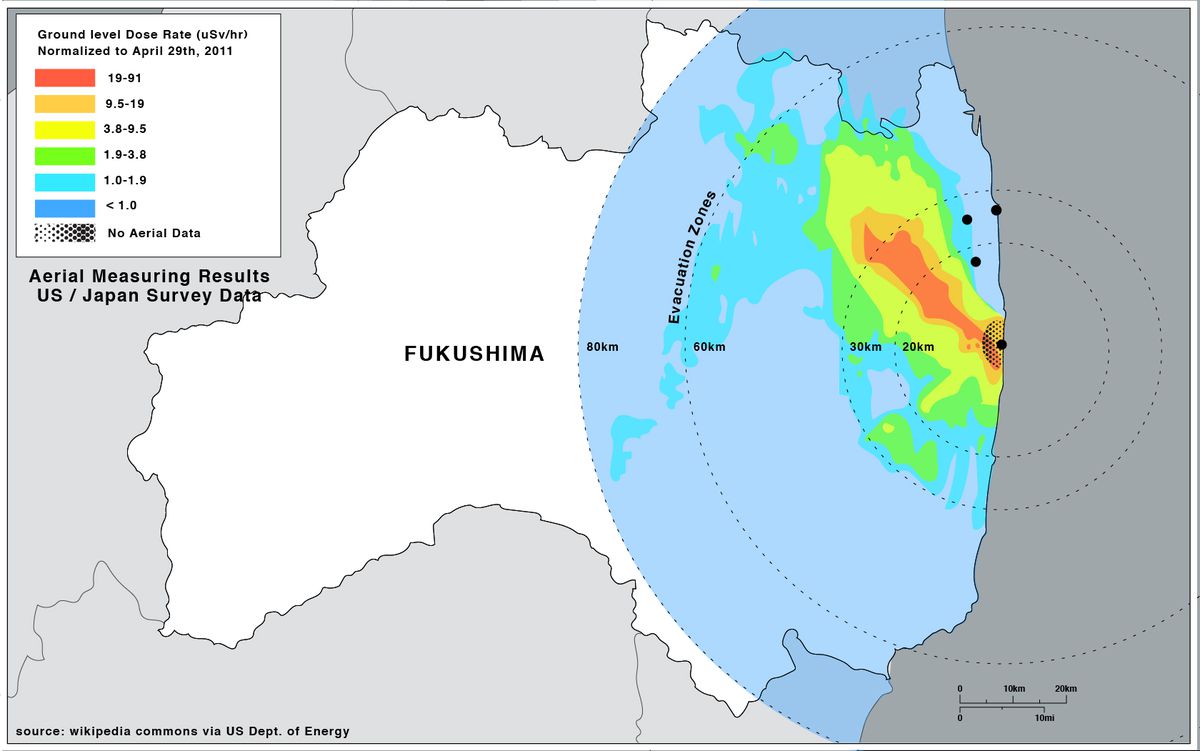

In the aftermath, there was no central resource for radiation information. The few radiation sensors TEPCO had installed in the region all went offline after they were flooded in the wake of the explosion. So where, exactly, was the contamination? How much radiation was there? What were the cancer and other health concerns, and for what people—elderly, pregnant, children? What could they eat? Where could they go?

Though very different in many ways, Fukushima’s nuclear accident was the largest since Chernobyl in 1986. Nobody knew what to expect, or what would ensue. Everybody feared the worst.

In those first tumultuous days, tech guru Sean Bonner frantically assembled and moderated an international Skype chat room from his home in Los Angeles. It consisted of 25 technology professionals, nuclear scientists, and public health experts, all trying to connect the pieces of a very complicated puzzle.

Bonner regularly worked in Tokyo, and now lives there. He had been planning a technology conference in the city in April. After he heard about the earthquake, he called his Japanese colleague, Joi Ito, to make sure he was safe. Thankfully, Ito was in Miami at the time, but when they dove into the internet to search for updates on what was unfolding in Japan and came up dry, they grew frustrated. They’d heard rumors about the Fukushima nuclear plant, but they couldn’t confirm anything. It took five days for the national government to release an official report in which they stated that not only had a nuclear accident occurred, but that radioactive fallout may have been carried to areas far outside the initial 20-kilometer evacuation zone.

“[The national government was] publishing really, really sporadic data, if and when they published anything at all,” says Bonner. Though neither he nor Ito had ever worked with radiation measurement tools, nor been trained in any sort of nuclear science, they felt the need to do something. Their connections in other industries put them through to more connections, and soon the Skype chat room was buzzing nonstop with ideas from bright minds around the world.

The group decided they must first define the problem: they needed standardized radiation measurements pinpointed to GPS locations. But when they searched online to purchase radiation detection devices, they couldn’t find any. The niche market of Geiger counters had crashed. In the years prior to March 2011, maybe a few hundred were being sold a month. Suddenly, demand had exploded to thousands of orders a day. Without personal measurement devices and without reliable information from TEPCO or the government, “People literally had no way of knowing what was polluted with cancer-causing radiation, and what wasn’t,” Bonner says.

To make matters more complicated, right after the accident, the national government rolled their radiation standards back to 1990s-era numbers, but only in select areas. As Bonner recalls, “People were like, ‘How is this number safe there? But literally across the street, a different number is safe?’”

He and Ito mobilized the chat room of experts and created an apolitical, not-for-profit organization called Safecast to centralize and crowdsource their efforts. Bonner changed the original concept of his April technology conference to focus on the nuclear radiation problem at hand, and invited everyone to Tokyo.

Until that point, standard international nuclear accident operating procedures measured radiation in averages across many square miles. “That’s like taking the weather in San Francisco and declaring a forecast for the entire state of California,” Bonner says. “It’s not wrong, but it’s also not helpful in any way.”

Within a week of the budding Safecast gang putting their heads together in a tiny Tokyo conference room, they’d invented multiple iterations of mobile Geiger counters that could trace GPS locations and radiation data from a moving car. Starting five weeks after the triple-disaster, they drove all around Fukushima, collecting scientifically sound information that intergovernmental bodies like the United Nations would later use in establishing a new standard for nuclear radiation information. They also deployed Geiger counters around the world to create a contextual database on what radiation levels were considered “normal,” and where.

When Safecast conducted its own monitoring in Fukushima, they found contamination varied street by street, sometimes house by house. As data-collecting volunteers drove around the prefecture, people would rush them, begging to know “the truth.” What was safe? What wasn’t? If volunteers had extra Geiger counters on hand, they’d hand them out and teach people how to operate them. (It’s easy: you switch it on, make sure one side is facing away from you, then walk around. When you’re done, you plug it into your computer and upload the data to Safecast’s easy-to-navigate website, and a radiation map can be generated.) The volunteers also pasted stickers on lamp posts and fences with the radiation measurements they’d recently taken, along with information about Safecast’s website and live data center.

The process differed sharply with government procedure. Bonner heard from many people that when government-deployed teams would collect measurements, “Vans would pull up with people in Tyvek suits who would [go] into their front yards and walk around with [monitoring] stuff, and then get back in, and drive away. And they’d be like, ‘What the fuck just happened?’ You know? That’s horrifying.”

Safecast decided early that all their data would be open source and designated as public domain so that everyday people and scientists alike could freely and forever access it. They also decided not to analyze the data, and refrained from declaring anything “safe” or “not safe.” Their only mission was to equip people with unfiltered, unedited information. They wanted people to make informed decisions on their own.

“We were saying, ‘Don’t trust us,’” Bonner explains. “‘Look through [the data] yourself. You take the device, you take the measurement, you’ll understand how it works. Trust that, don’t listen to what I’m telling you.’”

As more measurements streamed in, Bonner says, “What became obvious to us right away was that the evacuation areas were completely wrong, because they’d evacuated a perfect radius around the plant — basically a blast radius. … It didn’t take into account the weather or typography or any of that.” Some areas outside the evacuation zone registered high doses of radioactive material on Safecast devices, while some areas inside the zone registered the same as Tokyo — in other words, normal.

Safecast wasn’t the only group collecting data that may have raised the possibility the government-enforced evacuation zone was wrong. Right after the nuclear explosions, the U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration deployed airplanes to measure the radioactive fallout around the area, flying in a grid pattern to precisely map out the contamination. The NNSA shared that information with the Japanese government, but did not release it publically.

“Whether they looked at that data, whether they didn’t look at that data — it’s debatable and will never be known,” Bonner says. “But what we do know is that they knew what the contamination zone was when they set up incorrect evacuation zones, and they sat on [the information] for four or five months.”

Only after Safecast and other major organizations started publishing conclusive evidence that contradicted the national government’s actions did things change. “Then they started to readjust the evacuation zones based on what the actual data was,” Bonner says, which was weeks after March 11.

It took more than a year for an independent investigation to wrap up. The National Diet of Japan published a report in July 2012 admitting that all organizational bodies involved in Fukushima Daiichi — including TEPCO, the Nuclear Safety Commission, and the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry — “failed to correctly prepare and implement the most basic safety requirements, such as assessments of the probability of damage by earthquakes and tsunamis, countermeasures toward preparing for a severe accident caused by natural disasters, and safety measures for the public in the case of a larger release of radiation.” In other words, according to the report: “This accident was not a ‘natural disaster’ but clearly ‘man-made.’”

Regarding the botched recovery efforts, the report stated the prefecture lacked the necessary equipment to monitor radiation. Of the 24 monitoring posts in the area, 23 were either swept away or damaged by the earthquake and tsunami. Communications networks all over the prefecture were damaged to the extent that mobile monitoring posts wouldn’t work, either, and back-up monitoring cars sat idle due to the lack of fuel.

All this created “a very complicated social situation,” Bonner says, “because there was a mandatory evacuation zone, but then [also] an optional evacuation zone.” People didn’t know what to believe anymore. If they chose to evacuate, and their neighbor didn’t, did that look bad on them, or on their neighbor?

Kitaizumi Beach and most of Minamisoma City received voluntary evacuation orders four days following the triple-disaster. Many surfers continued to visit the beach while the area was nearly abandoned. Out of respect for those killed by the tsunami, they agreed amongst themselves to wait for the disaster’s third anniversary before they took their boards back into the waves, in observance of Sankaiki, the traditional mourning period for Buddhists. They watched from the sea wall as the water crested and curled, crashed and foamed, day in and day out as consistently as always, as if the tsunami and nuclear meltdown had never occurred.

In that time, the Japanese government continued to guard information and insist on control while activists tried to get their findings out in the world. Bonner says anti-nuclear activists, in particular, would approach areas with Geiger counters and measure a range of objects, “but only tell you about the one that was dangerous.” Unsurprisingly, depending on where you got your news, you likely got a different read on the situation. That still continues today.

“Trust is not a renewable resource,” Bonner says. “If you’re an authority on this and you blow the trust, you can’t just next week again say, ‘Trust us.’”

So when the mandatory evacuation orders lifted in 2016 with official “safe” approval from the government, with legitimately low radiation levels confirmed by Safecast and other third-parties, many people were skeptical. Now in 2020, most of the area’s residents still haven’t returned.

At 8 a.m. on a Friday morning in January, the ocean temperature off Kitazumi Beach is just 10 degrees Celsius, which equals 50 degrees Fahrenheit. Onlookers rub their palms together, exhaling foggy clouds that dissipate in the air. In the water, six surfers bob behind the rib cage-high waves. More are in the parking lot, pulling on thick neoprene suits. Okumoto stands atop the concrete seawall that separates the beach from the parking lot.

He lets the sea breeze soothe his light hangover as he surveys the scene: So much has changed since 2011, yet it’s quiet moments like these, watching the early-morning waves, that remind him that some slivers of life largely stay the same.

During the week, Okumoto splits his time between Fukushima University and meetings with local nonprofits, coalitions, and prefecture and municipal officials, with whom he consults on tourism campaigns, infrastructure decisions, and community-building projects as a financial advisor. After checking in with the surf scene at Kitaizumi, he’s due in the offices of Minamisoma City. He’s planning to introduce the city’s tourism manager to Adam Doering, a Canadian professor from southern Japan’s Wakayama University who researches ecotourism and surf culture.

As the sun lifts from the ocean, surfers alternately enter and return from the sea. Doering tucks his shoulder length hair into a neoprene hood and paddles into the waves. In the parking lot, Okumoto catches up with the rest of the surfers. Floppy wetsuits adorn car doors. Coffee steams. Smiles break into laughter. When one of the few local female surfers, Michi Iizuka, shows up, bundled in a knitted hat and coat and Ugg slippers, Okumoto rushes over to greet her. Iizuka’s eyes are sleepy, but perk up as they walk together to the top of the seawall and the ocean comes into view.

Okumoto points to her, says, “She is a great female surfer,” and then pauses, growing serious: “One of the only ones now.”

Iizuka nods. She lives 10 minutes down the street and visits Kitaizumi almost every day, if not to surf, then to watch the waves. “There used to be more women,” she says, heading back to her truck to change into her pink-accented wetsuit and get her surfboard. “Now most [women] live in Fukushima City. They only come here now on the weekends.”

Okumoto nods, aware that the evacuation orders have exacerbated the gender disparity at Kitaizumi’s beach. It’s mostly men who have chosen to return, partly due to the fact that there’s still no international standard for public dose-limits of radiation exposure. It’s generally understood that women (as well as children) have lower radiation thresholds than men, so they have been conservative when making decisions to return, especially after information was hidden and botched following the disaster.

“We want to bring the women and the children back,” Okumoto says. “There is so much here for everyone.”

Iizuka smiles, her eyes softening around the edges. “That would be so nice.”

Okumoto had picked up his hangover the previous night, when he and Doering met with Murohara and a few others in Fukushima’s surf community. Cramming themselves around the dinner table of a wood stove-heated house, they debated the future of Kitaizumi Beach until 2 a.m over homemade Korean hot pot, whiskey, and wine.

They discussed how best to build up Odaka and Minamisoma City’s tourism infrastructure. International ATMs are hard to find in the area, and with many accommodations yet to reopen, so are places to stay. Public information, like signs and bus schedules, is largely written only in Japanese kanji. Okumoto and Doering want to invest in improving this framework while simultaneously trying to lure more surfers and tourists. Murohara, on the other hand, believes that bringing in more visitors will motivate local businesses to become more accessible to foreigners in and of itself.

As a single man who’s lived his entire life in Odaka, Murohara always knew he wanted to return. Others needed financial encouragement. Every evacuee within the initial 20-kilometer evacuation zone received about $77,000 in compensation from TEPCO and the national government. In the 30-kilometer zone, evacuees received roughly $18,000, and businesses received more depending on their value. With this cash, people could buy new homes and set up new businesses outside of the evacuation zone, all while retaining ownership of their old properties in Fukushima. The national government offered to pay for renovations in buildings that had been damaged, or demolish them for free. TEPCO estimates total costs for accident repairs and reparations will add up to $202 billion.

There are still around 46,000 people who cannot return to their homes. Most of the streets in the towns of Namie and Okuma, which got the worst of the radioactive fallout, remain off-limits as decontamination efforts continue. Sections of Namie did reopen in April 2017, but as of December 2018 only 1,000 of the original 21,000 inhabitants have returned.

Odaka, which used to have 700 elementary school children across four different schools, now only has one school and 60 kids. In Minamisoma City, which never had mandatory evacuations, the population has dropped from 70,000 residents before the disaster to 50,000.

There are innumerable reasons why someone might choose not to return to a previously evacuated area. For the people who left Fukushima, that includes trauma, distrust, fear, and six years spent creating new lives elsewhere. Perhaps most tangible is the fact that, as people evacuated, businesses went with them, and there are now very few employment opportunities for people uninterested in working construction, nuclear decontamination, or decommissioning roles.

Despite the government subsidies available for new businesses, there’s a severe shortage of young workers in Fukushima. Likewise, young workers won’t move to Fukushima because there aren’t enough good jobs.

The prefecture has started building infrastructure for future industries in some of the larger abandoned rice patties and farms, namely robot and drone test fields. And renewable energy initiatives are underway: with the decline in nuclear energy, Japan now depends on foreign imports for more than 90 percent of its energy needs. The Fukushima prefecture has goals to reach 100 percent renewable energy by 2040.

Still, for most people, particularly women and young people, opportunities are slim. And that’s exactly where Murohara, Okumoto, and others like Doering think they can help. They believe ocean-based employment, staked in surf-tourism and creating positive connections to the ocean, can give the community a wealth of opportunities to regrow its roots.

It took three years to clear all the tsunami debris from the beach, and then another three to rebuild the bathrooms and parking lot after new construction and zoning policies were implemented in areas that had flooded during the 2011 tsunami. As surfers had done before the triple-disaster, so they did after: gathering for beach clean-up weekends to help prepare the space for the general public.

Last July, Kitaizumi celebrated its official, government-sanctioned grand “reopening.” Lifeguards, all surfers, staffed the beach for the first time since 2010. Happy Island Surf Tourism, revived in full force, helped create a “surf experience,” where people could learn how to surf. Murohara, Okumoto, and Doering all reveled in the day. It was a hit. 37,732 people attended, says the tourism office, and around 30 percent were kids.

“It’s a fact of the disappearing trauma,” Okumoto says. Though the trauma isn’t gone, he believes that slowly reintroducing people to the ocean — whether that’s by spreading photos of people at Kitaizumi, or getting them to visit the beach themselves — will accelerate the healing process.

Doering spent Kitaizumi’s opening day interviewing the lifeguards, who felt pressure to make the day run perfectly. Doering himself had only started surfing at Kitaizumi after the disaster, so the grand opening was the first time he’d ever seen families interacting with the waves. When he went back to the beach for a surf a few weeks later, he saw a mom watching her three kids in the water. A lifeguard was giving the children surf lessons before his shift started. He cheered from the beach, wanting to happy-cry in order to diffuse his joy. Slowly but surely, the people were coming back.

After a quick costume change in the beach parking lot — Doering from his wetsuit and into a button-up shirt, Okumoto from his bomber jacket and into a velvet blazer — the two sit down with Minamisoma City’s tourism manager Takeda Tomoyoshi at his office in city hall.

This year, the prefecture declined to offer money to the surf-tourism committee, but some funding has been approved via the municipal government. They’ll use most of it to pay the lifeguards, a welcome contribution to local employment, and hope enough will be left over to entice in a food truck to set up shop at Kitaizumi.

From a municipal perspective, Tomoyoshi understands the PR value of the beach. “If I go to Tokyo and I ask people, ‘Do you know the name “Minamisoma,”’ they don’t really know the name,” he says. “But they know ‘Kitaizumi,’ so that’s the real influence it has.”

Thanks to Murohara and Okumoto, the Japanese national shortboard and longboard championships will take place at Kitaizumi in June, the first major competition held there since 2010. Murohara says more than 600 competitors have already registered. And though the Olympics won’t venture up there, Happy Island Surf Tourism plans to capitalize on the attention that Japan and surfing’s Olympic debut have received.

Over the last year, through his international business connections, Murohara has brought surf industry executives and professional surfers to his manufacturing factory and shown them the highlights of Fukushima and Kitaizumi. M.S.P. now sponsors 10 competitive surfers.

Even if surfing’s economic contributions to the region are small, they are something in a town that not long ago had nothing. Perhaps even more powerful is the surf-related imagery: kids playing on the beach, families experiencing the water, lifeguards keeping people safe, all of which will gradually replace the photoshopped flowers and sensational headlines. Fukushima is on a journey for spiritual healing as much as economic, and surfing happens to offer a little bit of both.

Shortly after the triple-disaster, Okumoto says he hiked up the craggy cliffs south of Kitaizumi Beach. People set up a village there, on top of the bluff, about 5,000 years ago. They called themselves “Kaidzuka,” which means “shell hill” — they ate shellfish, Okumoto explains.

“The ancient people were very smart,” he says, reminiscing, looking up that way while standing on Kitaizumi Beach. “They know the strength of nature.”

Like the shrine by the playground on the hill behind the beach, the vast majority of shrines along the coast were spared from the tsunami, all built on hills in locations chosen hundreds or thousands of years ago.

When he stood on top of the bluff in the wake of the disaster, Okumoto peered straight down at the ocean, still processing its capacity for both violence and peace. For the first time in his life, he had seen the sea, the cliffs, and the sand without the cement seawalls; the section had been destroyed by the force of the waves.

“I suppose ancient people saw this scene,” he says, trailing off.

The sunsets at Kitaizumi Beach are soft and subtle, facing east into the infinite Pacific sprawl. The darkness gradually crawls up the sky, like an ombre curtain rising, and when it’s done, it’s day again.

That’s the beauty, isn’t it? Okumoto says, “The waves will always come.”

Recent Comments