One fundamental story, two plotlines, three basic tales, five boilerplate set-ups, or seven narrative archetypes: However many storytelling devices civilization boils down to, a quest – The Odyssey – tallies the most adventure. Here, then, unscrolls the first (slightly edited) third of an epic ATX arc, wherein the hero leaves College Station and builds a global music promotions empire that he exited last week.

Austin Chronicle: When we met a few weeks back and I asked where you were from, you said, “I’m one of the few people actually from College Station.” What did you mean by that?

Charlie Jones: You don’t know a lot of people in Austin that are from College Station, for sure. Could be the difference from conservative Texas – A&M. A lot of the friends that I grew up with are still there. My sister still lives there. My father, who recently passed away, still lived there. Great place to grow up; I was born there. As you get older, you meet a lot of people, but your close friends stay the same, and I still count as close friends a lot of the people I grew up with.

AC: Typical small-town Texas childhood?

CJ: That was a time when you could ride your bike all over the city, and I made a life history of cutting school. We would cut school with our backpacks and our fishing poles. We’d go fishing! Cutting school nowadays is different [laughs]. The whole Friday Night Lights thing was big, you know, Friday night football, Texas A&M football games on Saturday, barbecues, hanging out with your friends. That part of College Station was great, because it was still a small community.

When I graduated from high school and was going to be a freshman at Howard Payne University in Brownwood, which is another conservative town, that was right around the time MTV [exploded]. College Station was the first town – to my knowledge – that tried to ban MTV. I’m not kidding, this happened. It happened. It’s like some Footloose shit. I remember telling myself, “I couldn’t have gotten out of the town faster.”

I did go back for a period of time to attempt going down the college path and eventually tried to get into A&M, but I could never get in, which ended up steering me to Austin, so for better or worse, I ended up here. I left College Station and moved out to Hawaii for a summer, bartending and working at a golf course. My mom was like, “You need to get your shit together and go back to college.”

She convinced me, too: “You don’t need to come back here. Go to Austin.”

I came here and went to [Austin Community College], did some bartending, tried to get my grades up to hopefully get into UT. I remember telling Johnny Walker, the KLBJ deejay, that a moment with him on the radio here made me know I was home. I was driving on the upper deck of I-35 and I remember him coming on the air to announce the death of Stevie Ray Vaughan. He was very emotional, because they had known each other and Stevie Ray Vaughan had meant something to him.

He said something like, “Turn your lights on or pull over,” and the whole highway lit up. I almost started crying. Right then, I knew I was home, like, “This is my home.”

I still get emotional thinking about it today.

AC: What cast the shade from your eyes, so to speak, about College Station? Your friends all stayed, but what told you to leave?

CJ: It was a very small community where everybody knew everything and was always in your business. I wasn’t a bad kid, but I was in trouble a lot. I think, to some degree, I was running from that. I needed people to get out of my business. For lack of a better saying, I ran away from home – at 21 years old. That’s when I went to Hawaii.

It was a discovering time for me. I was trying to figure out who I was. Thank god for Mom. She slapped me through the phone, like, “Get on the plane, come home, and let’s get your life in order.”

“I ran away from home – at 21 years old. That’s when I went to Hawaii. Thank god for Mom. She slapped me through the phone, like, “Get on the plane, come home, and let’s get your life in order.”

AC: Is your mom Texan?

CJ: She was, yeah. She passed a couple years ago. That was a tough one. But yeah, my family is all very Texan. I have a great aunt that just passed. She was kind of like my grandmother. She passed at 101 or 102. She had a pretty good run. Still sharp as a tack. Her body gave out on her, but her mind never went.

In her husband’s and her retirement age, they spent all that time traveling the country in an RV doing genealogy and researching everything. They’d go to small towns and take pictures of gravesites, go into courthouses and get documents. When she passed, I got all of those documents. A certain part of my family dates back to the first legislature of Texas. I’ve been around.

AC: So what year did you move to Austin?

CJ: So, I moved here early ’90 or late ’89, somewhere right around there.

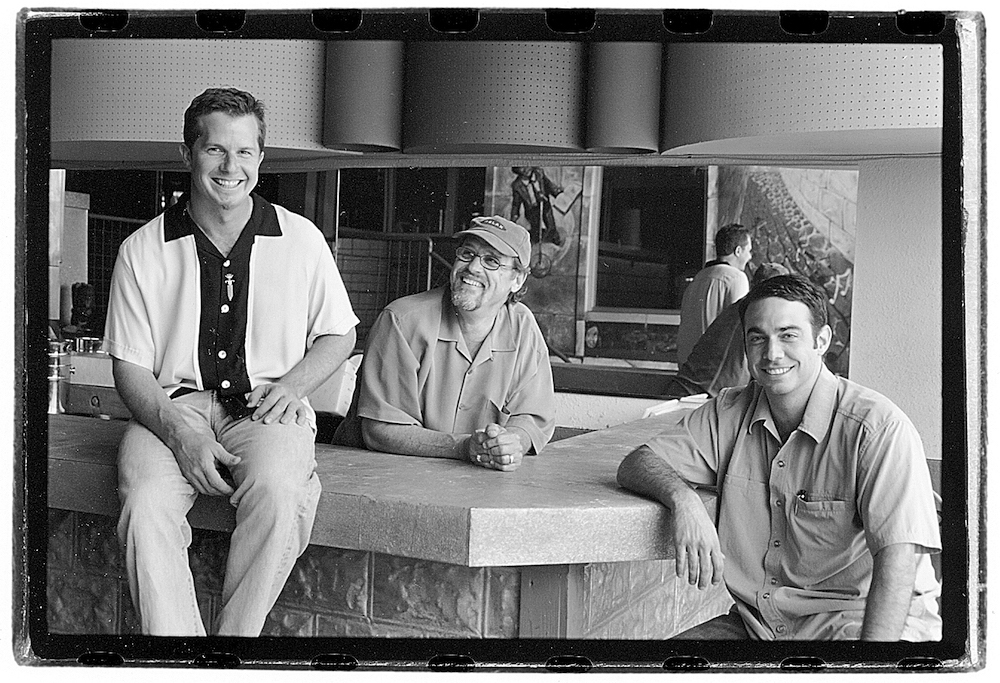

Charlie Jones (l) and Charles Attal (r) with Tim O’Connor circa the mid-Nineties (Photo by Todd V. Wolfson)

Sometimes You Have to Say “What the Fuck”

AC: You began working at Direct Events in 1993?

CJ: I was going to ACC and I’d signed up for a music management class, because that sounded fun and I needed something that I’d actually get a good grade in. The guy teaching it was Mike Mordecai, longtime musician here in town, and we had a great connection. He was friends with Tim O’Connor, who was opening up the Backyard. He was also friends with Tim’s wife, Allison, and she was looking for an intern. Mike called her, hooked me up, and I ended up becoming the intern for Allison Eklund at the Backyard – first season it opened, 1993.

I’d work in the office two days a week, answering the phones or sending out posters. You know, the old-school way of promoting concerts. On the weekends, if I wasn’t bartending, I’d also be the volunteer band runner. I’d show up, help Allison with catering, then I’d be available to the band’s tour manager, production manager to run somebody back and forth to the hotel, go to the music store. That’s what a runner does. That’s where I started.

AC: Any musicians stand out from that time? A lot of big acts played the Backyard in those early years.

CJ: The one that really stands out is Cyril Neville. I had an old Volkswagen Scirocco and my car broke down on the side of Southwest Parkway running back and forth with Cyrille Neville in the car. And I was freaked out. That was first generation flip phone, like the old Nokias, which Tim had given me. Luckily, I could call someone, but he was just so cool about it. He leaned the seat back. He had a jambox with him. He started playing music. He just chilled. “It’s all cool, man” [grins].

AC: So you took music management to hopefully get a good grade, you fall in with Mike Mordecai and Tim & Allison: Were you following music or did you and it simply cross paths.

CJ: Crossed paths. Music’s always been important in my life. At the same time, showing people a good time, whether it was a party or something else, was also a part of my life. I was the kid in high school that when the parents left town, I would throw the parties, kinda Risky Business style minus the bad things – just people wrecking the house.

I did that … forever. It was my skill set. And if I was at other people’s parties, I was the guy who would talk the police down when they showed up. I think I had it early on, and when I ended up at the Backyard, I just was curious. I did every job they would give me and I’ve told this story many, many times, and it’s a story currently crossing paths with my modern day life, but the show that changed me was Sarah McLachlan.

She was a Canadian singer I’d never heard of, but meanwhile there’s this sold-out show and it’s the first show I’m a band runner at – or whatever Allison and Tim had me doing. It was also the first show that rolled into the Backyard with 18-wheelers for production, full sound and lights. I mean the Backyard had never seen anything like this. I had never seen anything like it. So I just was as attentive and helpful as I could possibly be all day. Somebody on her tour, which I’m still friends with some of them today, dragged me up onstage and said, “Come watch the show.”

I stood behind the monitor board, and I was there when the lights were dark and came on. It was more of a theatrical-type performance, with choreographed singers, and then her voice. I had never heard a voice like that. I look out into the audience and see the connection with her and that audience, and right then I was like, “This is what I want to do.”

I think I probably finished that semester at ACC, but I never went back to school. I got offered a full-time job after that summer. Tim offered me a job for the ’94 season. There was kind of a path in the office, half doing construction and helping build the Backyard, and half production manager. I wore all hats: stacked chairs, fixed leaks in the bathroom, and helped catering. I just did everything. I worked my way up and then we opened the Austin Music Hall, where I was a promoter rep. I advanced all the shows and eventually moved into the office and helped book shows – whether it was La Zona Rosa, Austin Music Hall, or the Backyard.

AC: Not all dudes from College Station would necessarily connect with a female Canadian singer-songwriter. They’re listening to country music, right?

CJ: I don’t think I was ever a “country music” fan. Willie Nelson was, more or less, the soundtrack of our house. Forever. In my high school years, I listened to George Strait, but also Van Halen. I was a rocker. I listened to everything, but I can’t honestly say there was a female musician in my youth that moved me. I paid attention to them and remember them, whether it’s Carly Simon or … my mom listened to Olivia Newton-John. Whatever it might be, I heard it, but that was probably the moment where my brain expanded. My taste in music expanded.

“The show that changed me was Sarah McLachlan… That was the moment where my brain expanded. My taste in music expanded.”

AC: Working for Tim O’Connor, what was that like? Obviously he’s the preeminent promoter in Austin until the rise of the Charlies.

CJ: He’s a fixture in our industry for a long time. Besides learning a lot from him, he came at a time in my life and filled a role my father didn’t. He taught me a lot and I think I taught him a lot, and we cared for each other. I’m thankful for all those years. I still love him. When I run into Tim around town, he still looks the same. I know he’s had bouts with cancer and everything else, but he looks great. The last time I saw him – for something at the Paramount Theatre, I think, last year some time – he was happy and looked as good as he ever looked. I gave him a big hug.

When I left Direct Events, I remember the day I knew it was time to go. Tim had posters on the wall in his office of Earth Day, the festival he produced. Those posters inspired me. I would point, “That’s what I want to do.” And Tim and I worked on a couple outdoors things outside the Music Hall, where we closed the streets. I think it was called Moontower Madness. We did a Lance Armstrong Rock for the Roses thing out there too.

That was my first taste of doing something outside. It got my creative wheels running and I had some concepts. I pitched them to Tim and he wasn’t ready to go down that path. He’s like, “No, this is what we do. That’s not what we’re gonna do.” At that moment I knew I needed to start exploring other options – subconsciously. I don’t think I knew, “I need to go find another job.”

If you listen to the universe, it presents opportunities to you. You just have to pay attention. I don’t know if I even considered this an opportunity at the time, but my good friend Patrice Pike, the singer from Little Sister and Sister 7 – who is also one of the inspirations to music for me – hired me. Prior to me taking the job with the Backyard, going out for me consisted of Tuesday nights at the Black Cat, where it was Soulhat, Little Sister, and Joe Rockhead. Those days changed me. I loved it, you know, Pabst Blue Ribbon and $1 hot dogs – or free hot dogs and $1 Pabst beer!

I loved those days. We became good friends and she inspired me to love live original music, and that’s when she and the band got their Arista [Records] deal. It was their first time going out on tour and they had some tour support. They were the opening act for John Fogerty and their longtime tour manager, he was ready to pursue new opportunities, so she asked me, “I’ve got enough money to pay you what you’re making at the Backyard, would you like to be our tour manager?”

I was like, ” … Yes.” I resigned from Direct Events.

AC: Like going to Hawaii, you ran away from Direct Events!

CJ: I don’t even remember what I did with my stuff. I stayed at my friend Jake’s house and put stuff in storage. Then I spent two years with Sister 7 in a van. The first season, we opened for John Fogerty, so we got to go to all the great rooms and outdoor amphitheaters in the country, whether the Greek Theatre in [Berkeley] or Red Rocks – indoor places, outdoor places. I just learned. I got to watch and learn from every promoter, whether they were doing it good or doing it bad. I learned and saved money at the same time. When you’re on the road, you don’t have any expenses.

AC: You’ve mentioned outdoor shows. So much music takes place inside at night. Did you want to be outside?

CJ: Those days were about just learning the business of putting a show on: from load in to load out, how much it cost, revenue streams, and establishing relationships, which is as important as anything you do in life and business, but especially the music business, where relationships are everything. I was developing relationships. Outside happened to me first because I didn’t own a building [laughs].

The very first show I did, I basically started the business out of the back seat – the back bench – of the 15-passenger band that Sister 7 owned. The first show I did was a parking lot show behind the 606 Club and Wylie’s over in that area on Sixth Street back around Trinity. There’s a parking lot behind it, and I rented it and did an outdoor show on Halloween, because you know, there’s a sea of people. What could go wrong?

What could possibly go wrong?

I locked it up and did all of my permitting. I did everything right – before they even knew about it. I was learning lessons. I didn’t market it properly. Tim taught me this lesson one day that I didn’t realize was a lesson. We did a show in Galveston once. The beach packed with people, but inside our fence line – nobody. The lesson there: “Don’t compete with the beach” [laughs].

I’d see all these people on Halloween. And you know, it’s a free experience. You just want to be down there. You don’t want to pay for a ticket to go in a parking lot and see a band. And I had business owners down there battle me and police on me about the sound. I bought a decibel meter and learned the laws about sounds and dBs. So I executed the show exactly like I was supposed to and followed all the rules. I got a little bit of credibility with the city. The police were like, “Ah, you know, he operated correctly.”

And lost the $6,500 I had in my savings account.

AC: Who played?

CJ: Sister 7, Charlie Sexton … I still have the poster in my house. So I kept tour managing and did fee-for-hire productions, like a company launching a product that needed to book a band. I was making ends meet. The next venture where I put money up and actually produced an event was the Antone’s Blues Festival at Waterloo Park.

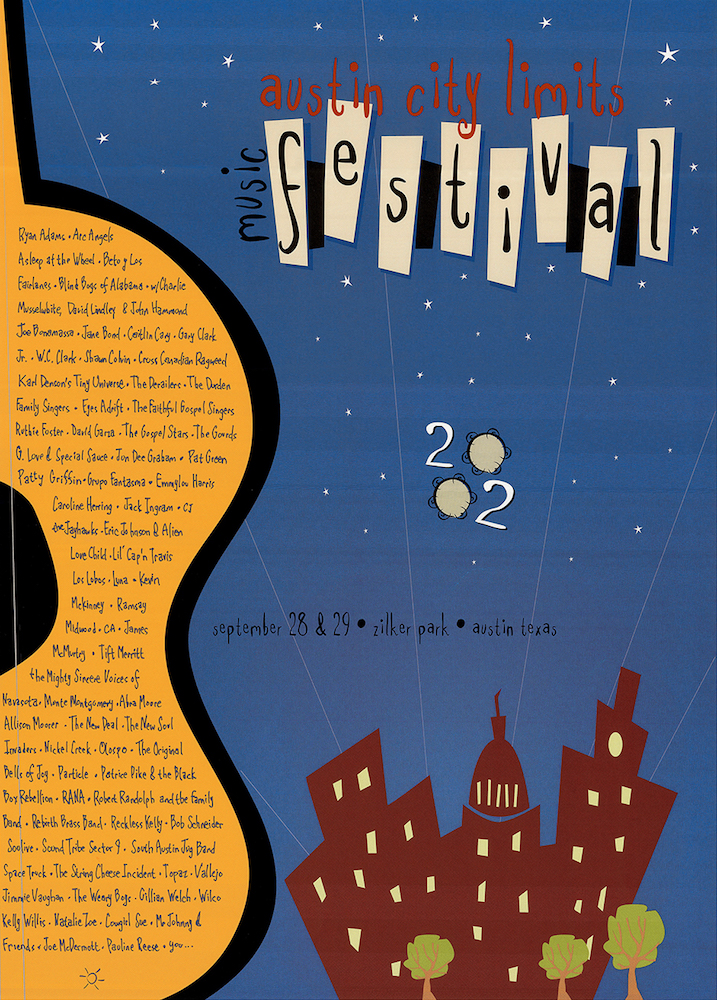

Flanked by Bill Stapleton (l) and Charles Attal onsite at Zilker Park, Jones helps prep the first year of ACL Fest, 2002 (Photo by Todd V. Wolfson)

Welcome to Festival, Texas

AC: John Lee Hooker headlined the Antone’s Blues Festival in 1999.

CJ: My carpe diem moments were all happening. There was that and the Lance Armstrong celebration that happened after his first Tour de France win. That first one turned out to be a great moment for me and the city, so my credibility within the [Austin] Parks Department went up because of the way I operated. Our business is filled with people that will tell you one thing and then do another, and I don’t think I ever did that. I honored my word. I followed the rules and didn’t cut corners. I just wanted to do it right.

So it becomes evident that Lance is going to win the Tour de France. I’m talking with the Lance Armstrong Foundation, because I’d known them from years before when I had done the Rock for the Roses thing for Tim. “Something needs to be done if he wins the Tour de France,” I told them. They’re like, “You know what? You’re right!” So they called the mayor’s office and we all had a couple conversations.

Sure enough, Lance wins the Tour de France. The mayor’s office and everyone else is like, “We gotta do something. Charlie can do it!” So we worked with the city, did a parade, and I did all the production and booked some bands. I choreographed the event with sky divers and the National Anthem and a video montage of Lance’s career. It was basically my first production and it was awesome. And I did it for free. Lance was my friend, and I love this city. People paid attention: “He knows what he’s doing.”

Fast forward a few months later and the city of Austin and the state of Texas are doing A2K, which at the time was touted as the largest organized mass gathering in Texas. They were closing everything Downtown and expecting 200,000-300,000 people, whatever. As it drew closer, I didn’t have any other work, so I called my contact at the mayor’s office, “Hey, y’all have any work?” They called me back and said, “Yes, we just might.”

I went and met with Mayor Kirk Watson and his Chief of Staff. They’re like, “The mayor would like to talk to you further, can you come back at the end of the day?” I went back after hours, I remember the mayor was in his office and there were papers everywhere. He’s got his team around him and he’s as stressed as you could possibly be. We’re digging into stuff and sometimes honesty is great and sometimes honesty’s too much for people. My foot has gone into my mouth many times in my career.

But at this moment, I was just like, “Mayor, you’re screwed. All these things people have promised you, they’re not happening. It’s go time. You’ve got to execute this.”

So they asked me to step in, take it over. I didn’t have the financial resources or the team, but they cut all red tape for me and told all city services, “All right, we’re organizing this and team Charlie is going to run the team. Do exactly what he says.” We had six weeks, not very much time, but we went boom, pulled it off. That was my first experience at a very large scale event working with all services within a city on an organized mass gathering.

“Our business is filled with people that will tell you one thing and then do another, and I don’t think I ever did that. I honored my word. I followed the rules and didn’t cut corners. I just wanted to do it right.”

AC: How many people showed up?

CJ: I think the city and the police department were saying 250,000 people. It was New Year’s Eve, and that’s when at midnight everyone expected the whole world to shut down. It didn’t, the show happened, and there were very few arrests. It was great! So Kirk was thankful, I had great relations with city services and the police department. It wasn’t premeditated, but my credibility elevated in the city as a producer.

That got me contracts at Auditorium Shores with the Parks Department. When I presented to them a couple ideas, one was a B.B. King blues tour [date]. I think that was one of the first ones there with seats. I remember some people living in the 78704 area that had been bitching about Auditorium Shores forever pulled me aside and said, “Nobody’s ever done a show like this down here,” and thanked me – for the attention to detail. We treated it like a proper seated show. We had G.A. around the seats; maybe I got that from being on tour with Sister 7 and playing amphitheaters.

I also worked with 101X to do 101X Fest down there, which proved the tail end of those radio festivals, where bands would play just to get their songs on the radio and ticket prices stayed pretty low. Well, that show blew up. Cypress Hill, Weezer, and maybe Outkast played – great line-up. All the stars aligned, show of the summer – sold out: 14,000-15,000 people. I don’t even know how big. It was just packed. And the show made a ton of money. I was producing on behalf of the radio station, so I had my fee and wound up making really good money, but I ended up handing the station a check for $200,000.

A lightbulb went off in my head of how you connect the dots of your revenue streams, the band bookings, the execution of the event – all that stuff – and then paying attention to the stuff you can’t learn in business school: the human experience. What do people need at that particular time? That’s the music, the type of service. I was learning that.

So once again, my credibility went up and it put me in a position to present to Kirk’s office and at that time Jesus Olivares, the director of the Parks Department, an idea to bring in a multi-stage, multi-day experience-based show – I compared it to the New Orleans Jazz Festival – to Zilker Park. And I got the contract. They hadn’t allowed a contract for something like that in Zilker Park since MTV’s Sports & Music Festival [in 1997], where they just tore the park up. They didn’t pay attention to the neighbors, they didn’t clean the park up, they didn’t fix it up. The city was scarred from that. “No more.”

I had developed a history of putting everything back, fixing everything, doing everything I said, and leaving the space I used in better condition than when I got it. That was our model. So I started shopping the idea to everybody I knew with money, whether the LBJS Broadcasting Company or investor-type people in town, but there was no business model that you can justify this kind of investment for this concept.

I had this pivotal moment in that I’d gotten a meeting with GSD&M [co-founder] Roy Spence, because his assistant Karen Greer had helped me with some of my shows and gave GSD&M resources to do some of my creative work that made me look like a bigger company than I really was. She was like, “I’ll get you a meeting with Roy.”

I got my meeting with Roy and pitched my idea. He listened and really engaged and loved it. I think at the time I was even pitching, “Maybe it’s a one-band [affair]. I need $1 million to book Garth Brooks or U2 and do a really big show.” He was the one that convinced me this city needed a cultural event. He’s like, “Really, you should think about an experience.”

That’s when I started focusing more on what became the ACL Festival and its creation. I formed a partnership with Bill Stapleton and Bart Knaggs, who represented Lance Armstrong. We met during the Lance Armstrong celebration on Auditorium Shores. They saw something in me and took a chance – brought me into their company – and were the financing behind getting the show up.

Charles [Attal] and I tell this story a lot. Prior to that time, he and I shared a little, 900-foot-square office on West Fifth Street over by El Arroyo. So Charles Attal Management was in one side of it and MiddleMan Music on the other, with no walls between us. Charles and Amy [Corbin] took up one half and Lisa Schickel and I occupied the other. We had a little table in the middle we could share, but when Charles’ phone rang, he’d have to step outside. He’d obviously be dealing with an agent. Then my phone would ring and it might be the same agent, same band. Kinda funny.

You know, we’d go to work late, then take off in the afternoon to go wakeboarding, because we couldn’t get our calls returned. We’d come back after a couple margaritas and wakeboarding, and about 7pm, the West Coast could take our calls.

Later, after the ACL Festival was agreed upon – and I don’t know if I had learned this or this was just instinctual – it became clear that to create an event the community feels real ownership in, they need to be a part of it from the very beginning. We put a civic stamp on it by the way we announced and also with the brand we aligned with, which was a longtime trusted PBS brand, Austin City Limits the TV show. We held a press conference in Zilker Park with the mayor and the Parks Department, and they announced it. We talked about it.

Charles showed up to the press conference and after it was over, I was small talking with people. Charles and I walked off and I’m like, “Look, you wanna be my partner?” I’ve always acknowledged he was a much better talent buyer. He had that skill set. He could burn calls. I just didn’t have that in me. I liked the band part, but I wasn’t the best negotiator and he was just better at staying in touch with what was current faster than me. He had a better skill set, but I was better at the logistics and production, and the organization of a large-scale mass gathering.

Right then, we hand shook on becoming partners. We never had any paper document until C3 was born in 2007.

Re-Branding: Austin City Limits & Lollapalooza

AC: So the first year of ACL Fest, 2002, how’d that go?

CJ: Day one, we’re kind of expecting 20,000 people, but a lot more showed up. People did what we asked them to do: They bought their tickets online. There really wasn’t the system in place to do the wristbanding, so you’re supposed to come down there and exchange your ticket for your wristband. Well, on day one – first year – everybody came early. The line was just … from the box office, down the street, up Robert E. Lee. It was borderline riot.

That was my first awakening to paying attention to a line.

How we satisfied that initial line was all hands on deck. Everybody grabbed a Home Depot-like nail belt stuffed full of wristbands and dispersed throughout the line taking everyone’s receipts and putting wristbands on them. If they didn’t have their receipt but had a good enough excuse, we gave them a wristband. Then the lines went from outside to inside: Porta-Can lines and definitely our food vendor lines. The food vendors weren’t prepared for something like this. The biggest negative feedback we had after the first year was obviously the lines. If you’re being responsible about your business, when there’s a problem you attack that, and we attacked that.

In year two, we obviously got more supplies, but we needed to figure out the formula for points of sale in the food area – how fast do they need to turn over food. We assembled a group of volunteers and interns and paid staffers who spent the day within the park paying attention to lines and times. So we started really fine tuning our model on the third year.

AC: Are those first five years of ACL Fest the blur of a steep learning curve?

CJ: It was an exciting time. There was no “job.” It was just our life. From that time until what I’m experiencing in my current life, I’m feeling what I felt back then, which was the positive energy in doing something that makes a difference – in your community, in your business, in your family’s life. Putting some money in your pocket!

All that stuff was lining up. And apparently we were growing really fast, because the fourth year of ACL was also the first year of Lollapalooza in Chicago. So after the second year of ACL, we started digging into other cities to take, not necessarily Austin City Limits to, but another type of event like this. Because it was a unique time.

The concert experience had dwindled in the fan base, which is the time CD sales finally started to slump. Ticket sales were slumping. Look at the ticket-buying experience, it wasn’t fun. You went to buy a $35 ticket, but by the time you paid for it, it’s $47.50. Then you had to go sit in traffic and pay for parking.

The concert experience was bad and ACL and Bonnaroo and Coachella came out at a time when fans needed something more. Those very large, multi-day, multi-stage, all-types-of-music filled a gap. Yes, the ticket cost more, but the value you got and the amount of bands you could see was amazing. It changed our industry.

“And apparently we were growing really fast, because the fourth year of ACL was also the first year of Lollapalooza in Chicago. So after the second year of ACL, we started digging into other cities to take, not necessarily Austin City Limits to, but another type of event like this.”

AC: You told Kevin Curtin and myself this great story about an intern coming to you one day in the office and informing you of an open meeting of the Chicago Parks Department the next day and that you dispatched someone that night to be there.

CJ: The Chicago Parks District held a meeting: “All right, we need to create a new event. It doesn’t matter where it is, we just need to create a new event.” The story was, we had interns in our office paying attention to all the markets we were looking at to possibly expand our model of these large, multi-day, multi-stage events.

We were learning about the culture of the cities and somebody spotted in one of the publications that there was a Chicago Park District meeting – or annual budget meeting, I’m not sure what it was – and on the agenda was the creation of a new event that would raise $250,000 for programs that were cut. So Stacey Rodriguez in our office got on a plane and crafted her speech for the amount of time allotted and closed with – after telling our story and explaining our business model – “We will guarantee the $250,000.”

That got me a meeting with the superintendent of the Chicago Park District a week later.

AC: At the point, had you already decided to revive the Lollapalooza brand?

CJ: The way that happened is that Bart Knaggs from Capital Sports Entertainment, who was responsible for our marketing and sponsorship, hired a marketing firm to do brand research on Austin City Limits. Where does it mean anything? Those firms do a lot of surveys so when we got their reports, they’d done surveys on entertainment categories. The brand that ranked No. 1 in every category? “Lollapalooza.” Not as an event, but as a recognized brand.

So when you thought of Lollapalooza, you might not have necessarily thought of the touring brand from the early-Nineties, but it could be the Bake Sale-Palooza at your kid’s school. It could be the Car Sale-Palooza. It could be the anything Palooza you have ever heard of. It became popular culture because of the Lollapalooza tours and music festival.

When I saw that, I recognized the value of Lollapalooza in our culture.

At the same time, Lollapalooza was coming out for the second round. It had gone out of business in ’97 and they’d bought it back in 2003 to do a tour. Charles and I aggressively chased a date to use at Auditorium Shores. They were doing amphitheater tours around the country and we were like, “We can give them a better experience.” I got a meeting with Perry [Farrell], and pitched him my idea – of having a real multi-day event and a carnival; have everything Lolla used to be and not these amphitheater tours.

Perry said, “Yeah, it’s a great idea.” And we didn’t get the date.

Then it comes back in 2004 – same way, same tour – and I continue this path with Perry, Perry Farrell: “This is a mistake. You need to bring it back to what it was and don’t do this tour.” He didn’t listen to me. Maybe not him, but the collective partners behind it. So the show went up for sale and stiffed across the country. They elected to take it down and cancel it again.

Perry and I met and it was almost like someone had died. I was like, “No, Perry, this is perfect. Now we can re-launch it as a standalone, real cultural event.” We did a deal to acquire the brand and take control of it.

This was on a parallel path with the city of Chicago. When we were planning this event in Chicago, we didn’t have a name. We didn’t know if we were going to be the Chicago Music Festival or the Chicago Cultural Arts. We didn’t know. We didn’t have a name. And Perry agreed we needed to figure this out. Do we do 25,000-person events in three or four cities?

So Bart Knaggs and I set out for Hulu Hut one evening, drinking margaritas. I think it was the day a boat went through the damn. The guy survived, but it ripped all his clothes off. We were there that day, drinking margaritas.

On our last margarita, none of the names felt right. We knew that as a no-name promoter it was going to be so difficult to educate a new community. We know nothing about the culture, we are not recognized, and we’re going to get our brains beat in with any of these brands that we want to launch. But if we take our deal with Perry Farrell and we slap Lollapalooza on this massive event that could happen in Chicago, everybody in the world will pay attention.

And they did. That was ’05.

Charlie, Charles & Charlie In Charge

AC: The two Austin Charlies then teamed up with Charlie Walker in 2007. He sat high up in the chain of command for Live Nation, the largest promoter in the known universe. Is that what attracted him, adding Lollapalooza to the ACL stable?

CJ: When I go back to the time when Charles [Attal] and I were competitors and friends, Charlie Walker was in that mix too. We were all friends and we have been friends for a long time. There was some talk of acquisitions from the big concert promotion companies in the United States. These shows we were doing popped up on the radars of all the big guys. There was interest. The only reason that these larger companies would want to do an acquisition with us, is they want us to do a bunch of these. They don’t want us to do two of these. They want us to do 15.

I don’t have that skill set – to scale up – but Charlie Walker does.

We went back and forth with a few companies and eventually passed on the deals and marched down our path. In December 2006, Charlie, Charles, and I, plus our wives – which at the time we called C6 – went to Costa Rica together on a vacation. We surfed, drank beer, barbecued. We hung out. And at the end of that trip, we decided we were all going to go back and tell our partners we were forming C3. We laughed about it, but you can’t deny the power of our three names. People are going to pay attention!

We were kind of joking, but there’s a lot of truth in that and it served us in multiple ways. One, the company C3 was authentic in that it was three Charlies. In any business scenario, whether it’s a music agent or the mayor’s office, they want to talk to the boss and on any given day, all three of us could be talking to three different bosses in three different cities around the country, and we’d all answer the same way. It served us well. We grew really fast.

Time of my life. Time of all three of our lives.

What we created was unique. Not saying we invented the wheel, but we brought a lot of passion into our industry. We brought a party. We brought a good fan experience. We paid attention to all of that. We took care of bands. We took care of agents, managers. You name it, we did it.

AC: You’re talking about 2007 to 2015, when C3 sold its controlling share to Live Nation?

CJ: We officially became C3 in the summer of ’07. That was still pretty much Charles Attal Presents, Capital Sports Entertainment, and the festivals were in place. Walker was aboard.

Right about that time, he took the reigns and changed the direction of our company. I remember the first day, when Charlie sat with our staff and ran his power point on how we do business. He realized we would never have gotten where we are without doing it the way we did it, but he was going to change the way we operate.

No one Charlie knew everything. There’s not one person at these companies that can do everything. As a team, we can divide and conquer. He knew how to do that and did it. It was a lot fun and a lot of energy and a lot of risk.

The very first show we all risked was called Big State Country Music Festival – in College Station [laughs] – and we couldn’t have missed the mark any more. We almost bankrupted our company in its first year. We learned some really hard lessons, like we weren’t invincible. We had to be mindful of our approach from all the things that matter in business, most specifically, culture.

When we got back to the office – and I remember walking through our halls, depressed, head down, tail between my legs – we had just done one of the greatest country music festivals ever. It had stock car racing, barbecue and camping, multiple stages, and Willie [Nelson] played. Everything you need. But there wasn’t one person in our office that listened to country music.

So it was a lesson about culture. You have to pay attention.

“In December 2006, Charlie, Charles, and I, plus our wives – which at the time we called C6 – went to Costa Rica together on a vacation. We surfed, drank beer, barbecued. We hung out. And at the end of that trip, we decided that we were all going to go back and tell our partners we were forming C3.”

AC: So C3 wasn’t simply dreaming about staging Lolla in other markets.

CJ: The scaling of Lolla was definitely on the radar, but yeah, Big State was our first one. And with Lolla, we chose not to scale it in the United States because of a verbal agreement between myself and then-Mayor [Richard] Daley of Chicago, who really saw what Lollapalooza was doing for the Parks District and for the economy in the summer on a very slow weekend.

He told me one time, “Charlie, you know why I support Lollapalooza in Grant Park?” “No, sir, Mr. Mayor.” He’s like, “It will bring young people downtown to Grant Park to experience art and music, and when they get older they will give back.” He was just matter-of-fact about it. I was like, “You might have a point.”

But as we scaled that event bigger and bigger in their park, as per our agreement, they got concerned: “Oh, now you’re going to do this all over.” So I gave them my word Lollapalooza would live in Chicago, and if we were going to scale it up, we would do so out of the country. Our campaign evolved into “Lolla Lives Here.” Big billboards on the side of buildings in Chicago would have the Lollapalooza logo and then a CTA train. Everything reflected Chicago, and we immersed ourselves in that city.

The first time we elected to go out of Chicago began as a meeting for what became our very first one, which was in Chile with our now Chilean partners. They came for a meeting in our trailer at Lollapalooza. The William Morris Agency, also one of our partners in Lollapalooza, set it up and these young promoters had done all of their homework. They had acquired the rights to the big downtown urban park in Santiago, Chile, and were going to be the only ones allowed to use it. They had paperwork from the mayor’s office that they had the deal done. Then they had all their paperwork from the bank. They had the proper amount of money in place.

And when we called around and asked about them, they had done their job as promoters. They honored their contracts and treated their bands right. They reminded us a little bit of us when we were younger. They were passionate and just had a very good vibe to them.

And those guys got their brains beat in.

Lollapalooza was the first event of its kind for sure in Chile, but maybe in South America too, where it was a big American brand. We were required to do everything through the website. Nobody had ever done that. All your information had to come through the website. It had to come in and out of your inbox, which from our point of view, that promotes a safe event.

The more you tell people, the more you give them, the happier they are. We were probably the first event in South America that had all these stages, that advertised all kinds of stuff, and then actually did it. But… It was an expensive ticket and it was hard for the Chileans to acquire tickets, because it wasn’t their traditional way of going to the outlet and getting the hard paper ticket.

And again, they got their brains beat in financially. I think some of their backers bailed and a new group came in. They stuck with it and it took several years for it to finally get to where it was making a little money, and now it’s one of the most profitable shows in the world.

AC: So then Lolla hit the road.

CJ: Yeah, it went to Brazil and Argentina and eventually headed over to Europe, where it became more of a business model to scale it. Lollapalooza as that kind of event became a cultural icon in music. Pop culture in the Western world, and specifically the United States, drives a lot of culture around the world, whether it’s fashion, music, movies.

Finger Prints & Four Leaf Clovers

AC: After the Live Nation acquisition, Charles Attal told the Chronicle that the deal allowed C3 Presents to continue doing what it was already doing without fear of one show such as Big State taking it down.

CJ: Yeah, one hurricane isn’t going to take down ACL, but two in a row? There’s no telling what can happen, so he’s right. Very right. We took on some financial partners throughout the years that would allow us to scale up, because there’s a lot of risk and nobody has that kind of money to do those kinds of events. They’re very expensive, very complicated.

AC: So the Live Nation deal felt natural: Charlie Walker had come from there and the business had grown. You put together a model that a global—

CJ: I get a lot of credit for that, but that all changed when Charlie [Walker] came onboard with his management style.

If we were gardeners, I could make a beautiful purple zucchini. I might be able to make an orange one, too – a couple of them. Charlie can’t go make that. But once I know how to make my purple one, he can go make 100 of them.

My fingerprints on certain things became his fingerprints. He’s a machine. If I got elected to be president of the United States, I’d make him my chief of staff. If I was in the Army, I’d want him to be my general. He’s a very brilliant business mind.

AC: When C3 put on the Easter Egg Roll at the White House, did you get to meet the president and the first lady?

CJ: I’d met [Barack Obama] a couple times. I met him first when he was on the campaign trail against Hilary in the primaries. He had been doing these little rallies, and their tour was taking them through Austin. I guess their advance team had reached out to City Hall, “We’re coming to Austin and we want to do something. Point us in the right direction for somebody that could help us.” The call came into our company from City Hall.

AC: What year is this?

CJ: This would’ve been in … 2007? So I guess right at the beginning of C3.

Somebody called from the front desk maybe, and was like, “Hey, one of the candidates is doing a tour and looking for help. Who should I send it to in the company?” I was like, “Me.” I called back the campaign, “What are you looking for?” And you could tell it was just a junior advance person who had no idea what they were doing.

“Oh, we just need a little stage and microphone. He’s going to give a speech.”

I was like, “You don’t know what you’re in for, do you?” ‘Cause I could feel it. I was like, “This town could come out to embrace a candidate like this.” This guy might actually be president. I said, “Why don’t you let us help you do this?”

So I put a production team on it and we did it down on Auditorium Shores with a stage and a real P.A. system. And sure enough, that’s when the campaign changed. Because it went from doing a couple thousand people to here, where 15,000 or 20,000 people showed up. He was on fire. Very eloquent speaker, so you could just feel the momentum in his campaign change. I met him afterwards and he was thanking us for all our help. I’m shaking his hand thinking, “You’re going to be president, no doubt.”

The next time we got to meet him was along the path of all we had done. We were fortunate to do that night in Grant Park – when he was elected president – and we developed a rapport with the campaign as they transitioned into the inaugural committee. We were brought on to do the production services for the first inauguration. It’s a multiple-day event, so the first one was the We Are One Concert, which happened at the Lincoln Memorial and was a big television broadcast that had Garth Brooks and U2, the biggest bands in the world, plus A-list actors: Denzel Washington, you name it. We did all the production for that.

It was so awesome to be a part of that and to be a part of our country’s culture at that time. It was in the air, you know? And the air was hope and change. Everywhere.

Our team also worked with the military and did the Military Presidential Parade. That came after he was actually inaugurated, which was 15 degrees outside. It was freezing.

“That all changed when Charlie [Walker] came onboard with his management style. If we were gardeners, I could make a beautiful purple zucchini. I might be able to make an orange one, too – a couple of them. Charlie can’t go make that. But once I know how to make my purple one, he can go make 100 of them. He’s a machine. If I got elected to be president of the United States, I’d make him my chief of staff.”

But after the We Are One Concert was over and the president was taken from behind the Lincoln Memorial out to the backside where they had a tour bus and motorcade, the only people he talked to – him and Vice President Biden – was me and Charlie and Charles, and a couple of our production people. We had had all the bands and all the speakers sign a couple of guitars, and we gave him the guitars. It was a pretty cool day.

AC: So Live Nation buys the first half of C3 Presents in 2015, but when did they buy the rest?

CJ: A couple years ago.

AC: 2018?

CJ: I guess. I don’t remember exactly.

AC: Was that a moment for you? Like, “Now they own this”?

CJ: Possibly. It was still all great. Great things were happening to our company. We were growing. It gave a lot of our staff opportunities to grow in other markets and other parts of Live Nation if they chose to. For the most part, we operated as we always have.

AC: What changed for you between 2015 and the moment you decided to leave?

CJ: Early on, we were very involved in everything that happened. As we grew as a company and grew to 200 employees and shows around the world, my fingerprints aren’t really on it anymore. I think I went through a period of time [sighs], and I have to be careful about these words where … [long pause].

I think the lifestyle compromised certain parts of my life. It put me in danger of losing my family and it almost killed me. Well not almost killed me, but it almost destroyed my family, and more importantly, it almost destroyed me. Just the rock & roll lifestyle and everything that comes along with it. You know, not to quote Dante, but at the halfway point in my life I lost my way.

I’d gone down a dark path.

AC: So what’s the moment when you decide, “I’m leaving this. I’m going to start again”?

CJ: We’re in the middle of that transition as we speak.

AC: But there’s that moment when you decide and it’s both scary and exciting.

CJ: Toward the end of last year. My two partners, Charles and Charlie, could not have supported me any more. Whatever I needed to do for myself and for my family and for my future, they gave 100% support. It took a long time to navigate what was right for me, and we made a decision at the end of last year – and it was a hard one. Besides my family, what we have done in creating C3 is the most important thing in my life.

It felt like it was a transitional time for me and an opportunity for me to go focus on new ventures that whether they’re cause-related or whatever it might be, it was time for me to step away from C3. I mean the team is already running it. My fingerprints are no longer on it. I’ll miss my partners and my company more than anything [voice cracks].

“I’m at beautiful place in my life where I can do what I want. I can influence change positively by my own actions, and that’s what I want to do.”

AC: What’s your new company called?

CJ: Four Leaf. The Four Leaf thing is I find them, all the time everywhere. If you need me to go in your backyard and find you one, I’ll find you one. I see the pattern. My dad taught me when I was kid and he always had one on his desk. “How you find that?” “You have to look.” I just always look. The only place I’ve never found one is Zilker Park, which is my luckiest place in the world.

AC: And your offices will be housed out of the old Wiggy’s building on West Sixth. I got the sense you’re not wanting to confine yourself to music, so what’s the first path you’re going down?

CJ: We’ll have a couple of event concepts that we’ll announce in the coming months, but that’s a to-be-continued. Right now, I have the final creative designs with me and the LLC was all formed yesterday.

AC: Will you veer away from music? Like there’s more to organize than simply music events.

CJ: Music is in my soul. It’s a way to bring people together. But it’s also a platform to deliver a message. I think I’m going to be focused on stuff like that going forward. My first event, which I can’t divulge just yet, is very purpose-driven, with a very strong message. I’m at beautiful place in my life where I can do what I want. I can influence change positively by my own actions, and that’s what I want to do.

AC: This was the last question I asked Charles Attal during our C3 interview in 2015: What do you listen to?

CJ: In my car right now is Kendrick Lamar. Last night as I was cooking my daughter and all her friends hamburgers, I was listening to Nathaniel Rateliff. Then it might be Solange, then it might be Pearl Jam. I’m kind of all over the place. I don’t like a lot of any one genre of music.

AC: All right, desert island time: one group. What’s the one group?

CJ: It’d have to be Pearl Jam. I’m that guy.

A version of this article appeared in print on February 28, 2020 with the headline: Time of Your Life, Kid

Recent Comments